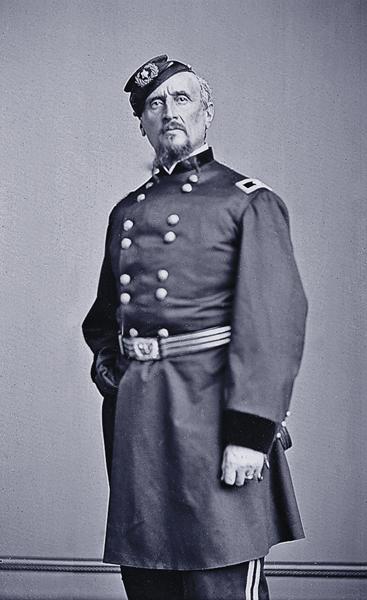

Frenchman Philippe Régis de Trobriand settled in New York City in the 1840s and served with the Union Army during the Civil War. The Army retained Brig. Gen. de Trobriand at the end of that conflict, and he went on to serve as a colonel in the Dakota Territory during the turbulent post-war years. A superb writer and excellent artist, he left behind journals that provide an exceptional vision of military life on the Northern Plains.

In late 1868, de Trobriand found himself with a real fight on his hands, against a persistent foe. His enemy was not the usual Indians raiding his post at Fort Stevenson in present-day North Dakota. On the afternoon of November 3, clouds darkened the horizon. At first, the distant plumes of boiling smoke were a curiosity, but then he could see strong winds were driving a fire directly toward the post.

Despite rosy predictions that the fire would burn out before reaching the fort, de Trobriand ordered the guardhouse prisoners to cut willows and bundle them for fighting the fire. For a while, the fort seemed destined to avoid the conflagration. Portions of the fire reached the Missouri River, and in other places, the fire seemed to turn back on itself and flicker out. Yet fickle winds swept up a wall of flame, threatening disaster anew.

In a most unmilitary fashion, Col. de Trobriand called his men to action, shouting, “Everybody out!” Roughly 80 men scrambled out of the buildings and began swatting and stamping out the flames.

Throughout repeated “charges” and “retreats” of his troops, de Trobriand affected the air of an aloof Victorian officer, standing his ground, despite being engulfed by blinding and choking fumes leavened with burning embers. He took no part in physically assisting his men in the work of the moment.

The colonel ordered a retreat to a road and conceived a tactic that is still used in wildland firefighting. He had a portion of his men fight the fire at the road’s edge, while another detail attacked spot fires that developed as winds carried embers over this narrow barrier. Once an area was burnt over and the leading edge of flames extinguished, the blackened ground served as a bastion against further encroachment.

Shifting soldiers from one point of danger to another, de Trobriand isolated a defensible area around the main post buildings. The post was saved, and all off-duty men were back in their bunks by eight that evening.

Survival Tip: How to Cook Outside Without Spreading a Fire

On the frontier, being able to cook without spreading a fire was a matter of life and death. A prairie fire can spread, well, like wildfire, as it quickly encompasses thousands of acres, with the potential to kill almost every living thing in its path. Historical pyromaniacs, like 1830s Plains explorer Francesco Arese, who loved to watch the prairie burn at night, while sipping champagne, and 1830s Fort Clark fur trader Francis Chadron, who set fires in the Dakota Territory out of boredom, were unusual. Most people took great care to assure that the cooking fire remained under control. For an outdoors hearth, dig a deep pit and encircle it with stones for additional protection. Be careful when cooking foods rich in grease and oils, as they can ignite a sudden and potentially deadly grease fire. The grease flares up and, in an instant, scorches clothes and skin, and removes facial hair. Keep a bag of salt handy (do not pour water as it will create a fireball). Salt poured on the burning grease will quickly extinguish the flames.

History in Art

By Illustrator Andy Thomas

The painting shows the latter stage of the incident, when Philippe Régis de Trobriand has pulled the troopers back to the road. Some are fighting the fire at the road, while others handle maverick flames that have leapt past it.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy National archives –

The painting shows the latter stage of the incident, when Philippe Régis de Trobriand has pulled the troopers back to the road. Some are fighting the fire at the road, while others handle maverick flames that have leapt past it.

– By Illustrator Andy Thomas –

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

– True West archives –