How do you solve a murder case that’s 150 years cold? It’s not easy, not when you can’t examine the victims’ bodies, and all you have to go on is a series of case files scattered in a dozen archives. But when Douglas Scott and I heard that no one had solved this apparent multiple homicide, we couldn’t resist the challenge. We thought maybe we could do it.

How do you solve a murder case that’s 150 years cold? It’s not easy, not when you can’t examine the victims’ bodies, and all you have to go on is a series of case files scattered in a dozen archives. But when Douglas Scott and I heard that no one had solved this apparent multiple homicide, we couldn’t resist the challenge. We thought maybe we could do it.

Scott and I are historical archaeologists, the kind who specialize in studying human activity in the context of written or oral records. We have both spent our careers working for the National Park Service, digging up Old West towns, 19th-century battlegrounds and military forts, and researching archives to uncover the secrets of the past. In addition, Scott is one of the world’s foremost experts on figuring out people’s life stories from analysis of their bones. He rewrote the details of the so-called “Custer’s Last Stand” at the Little Big Horn River in Montana in the 1980s, and his forensic expertise has been used worldwide in determining the causes of battle-related deaths on human remains. He even testified at the trial of Saddam Hussein, sharing firearms evidence that indicated massacre victims had been executed by firing squad. When I asked Scott if he would help me solve the mystery of the four murder victims at Fort Union National Monument in New Mexico, he said, “Sure, why not.”

The case starts with backhoe operator Martin Archuleta, who found an isolated grave in April 1958, when he started grading the site for the new superintendent’s residence at Fort Union. Located a mile away from the adobe ruins of the fort, this modern house, two others and a maintenance complex, when completed, would be hidden from the view of fort visitors because they lay below a dip in the topography. With a panorama of empty plains spread before him, Archuleta probably felt isolated from the entire world as he began his construction work.

I can imagine how eerie he must have felt, then, when his blade uncovered not one, not two, but three human skulls. I wonder if he saw the bullet holes in the skulls. They must have been hard to miss.

Crime Scene: Fort Union

Fort Union lies on the windswept plains of north-central New Mexico. Established in 1851 to protect the travelers on the Santa Fe Trail and to enforce the territorial boundary of New Mexico, it eventually became the site of a major military supply depot for the U.S. Army. During the Civil War, Fort Union supported both Army troops and Colorado and New Mexico Volunteers who stopped Confederate forces under the command of Brig. Gen. Henry H. Sibley at Glorieta Pass, near Santa Fe. This victory virtually ended the Civil War in the West, and it also vanquished Southern aspirations to connect the California goldfields to the Confederacy. Fort Union continued to provide supplies and logistical support to the Army during the Indian Wars of the 1870s-80s until the construction of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad. By 1891, the fort was decommissioned.

The eastern plains of New Mexico fostered its fair share of violence in the second half of the 19th century. Utes, Apaches, Comanches and Kiowas ranged the plains to the north, east and south of the fort in a sort of no-man’s and everyman’s land of dwindling buffalo and antelope herds. Comancheros—whiskey, gun and ammunition traders—roamed the area, supplying the Indians with illicit goods. Notorious bandits, such as Jesse James and Black Jack Ketchum, used the canyons and vast wastelands to hide from the law. All of these people took advantage of wagon trains that plied the Santa Fe Trail, and the troops at Fort Union stayed busy guarding supplies as they traveled the dangerous route from forts in Kansas to New Mexico.

The Excavation

When Archuleta reported his gruesome find, a National Park Service archaeologist conducted a formal excavation. He dug up not just three, but four men buried in a shallow, common grave near the Civil War-era star-shaped fortification that had been abandoned in April 1863. In a report published in 1975, Charles Randall Morrison described four “Mexicans” in their mid- to late 20s. They had worn few clothes when they went to their grave, probably no shoes or boots, and only one man wore a belt with a buckle. The buttons found in the grave were mismatched, of wood and bone, and in only one case, were made of the simple white china found so often on shirts of the mid-19th century. One man wore a shell pendant, strung on a leather string around his neck, and a single turquoise bead on a bracelet at his wrist.

But the evidence of violence in the grave was what so impressed Morrison. Three of the skulls had bullet holes in them, and the fourth’s skull had been smashed. One man appeared to have been stabbed by a bayonet or a knife; another suffered multiple breaks to his left leg. A third was missing two vertebrae and had a broken arm. Bullets of different caliber littered the grave.

Morrison’s report read like a horror story, suggesting that the men were victims of clandestine violence, an illicit “mass murder.” “His legs were ruined,” Morrison wrote of one man. “FU-2 was clubbed to death,” he wrote of another. “He was stabbed after being taken captive,” and “FU-1 and FU-2 were brutalized after capture.”

After identifying one bullet as a .50 caliber slug, ammunition archaeologists, at that time, believed was not used by the Army until 1863, Morrison concluded that the burial could not have occurred before the third and final fort was constructed in 1863. The grave’s location below the view of the third fort convinced Morrison that the burial was clandestine. “Buried where they were, civilian discovery could be minimized,” he wrote. “The conclusion is that at least some members of the military establishment at Fort Union ‘covered-up’ and sanctioned an illegal execution of native civilians, possibly between 1863 and 1872.”

Scott and I had our doubts. We knew that, at that time, the Army in New Mexico was in a state of military law, so a cover-up would not have been needed. Any execution of native civilians by the military would have been considered legal under any circumstances. We also knew that, during that period, Indians were rarely taken prisoner and then executed; they were killed as enemies at a site of battle and left for their relatives to find. They would not have been buried near the fort.

Based on the original identification of the men as “Mexicans,” we thought they may have been New Mexico volunteers. Perhaps these men were soldiers who had committed a capital offense that resulted in their execution by firing squad.

Digging Deeper

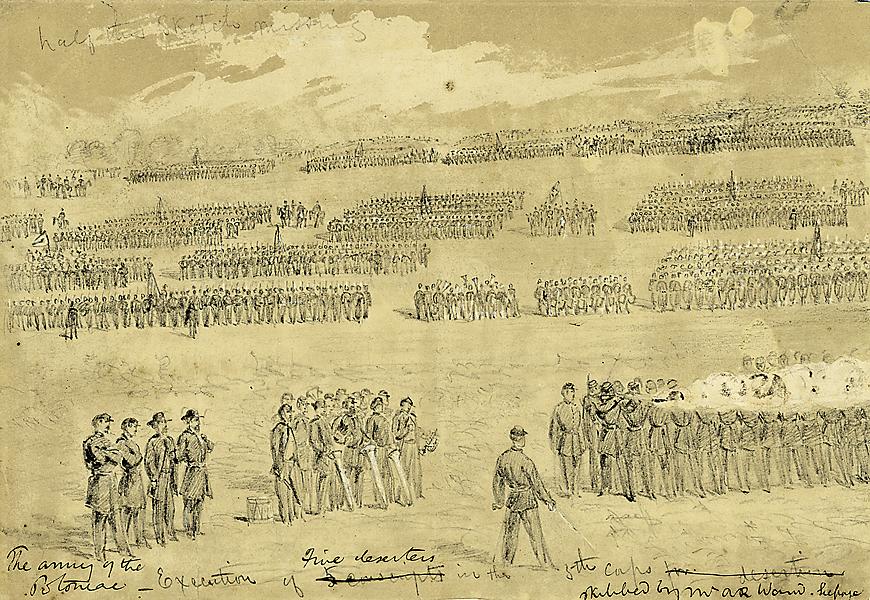

Some experts have said that the U.S. military executed almost 500 soldiers between 1776 and 1965; more than half of those executions occurred during the Civil War. The crimes for which a soldier could be executed, as specified by the Articles of War adopted in 1806, included mutiny, disobeying the command of a superior officer, desertion during wartime, espionage and murder. Records of these war crime executions in the West between 1862-63 are spotty and inconsistent due to confusion over the appeals process and the rapid turnover of command at some forts, including Fort Union.

Because the bodies and artifacts had been repatriated to the Ute Mountain Ute and Jicarilla Apache tribes in 2007, we could not re-examine the evidence directly. Therefore, Scott reviewed the notes and articles about the military artifacts and the forensic investigations. I went to the Library of Congress and the National Archives in Washington, D.C., and to the New Mexico State Archives to examine the military records. We both studied the records of military executions in New Mexico.

Scott discovered that the .50 caliber slug was probably a .52 caliber bullet, which today we know were both issued and used for years after 1861. He also noticed that one of the “artifacts” found in the burial was a piece of iron imbedded near the knee of one of the victims. Could it have been shrapnel? Could this man have been hit by cannon-fire?

We knew that cannon had been used in only two places in New Mexico, and both during the Civil War: the Battle of Valverde in February 1862 and the Battle of Glorieta Pass in March 1862. Could this man have been wounded at one of those two battles?

Based on contradictory evidence gathered by physical anthropologists over the years, we set about determining the racial background of the victims. The National Park Service and the tribes had determined the men were three Indians and a white man. Because the white man was buried with the three Indians, they had considered him to be “culturally affiliated” with the Indians, therefore his body was repatriated with the others in 2007.

We talked with the recently deceased and renowned physical anthropologist Christy Turner, who had examined the skeletal remains of the victims in 1959 for Northern Arizona State University. He told us that in the 50-some years since he had examined the bones, scientists discovered it is virtually impossible to distinguish Athabaskan-speaking people from Hispanics because of the shape and size of teeth. Knowing that the most likely Athabaskan speakers near Fort Union were Apaches, Scott and I concluded the men in the grave were either: three Apaches and a white man; three Apaches and one Hispanic; four Apaches; or any number of other combinations of the three races.

The bullet holes in the skulls were a key point of evidence for us. Morrison had assumed these holes evidenced mortal wounds. We thought they were evidence of a coup de grace administered to men who were dying of other wounds, or perhaps already dead. Not only did three of the skulls contain bullet holes entering from the front (but not always straight ahead), but also the skull that had been crushed had evidence of a bullet hole that passed from one side of the head to the other. Scott’s analysis showed that, in one case, the firing angle could only be from above, at a body lying on the ground.

For almost three years, with our findings in hand, I researched the military records of executions of New Mexico Volunteers, who were almost universally Hispanic, for military crimes committed during the Civil War in New Mexico.

Then we found it, the newspaper article that explained it all.

Hard News

The Rocky Mountain News of Denver, Colorado, reported on April 26, 1862:

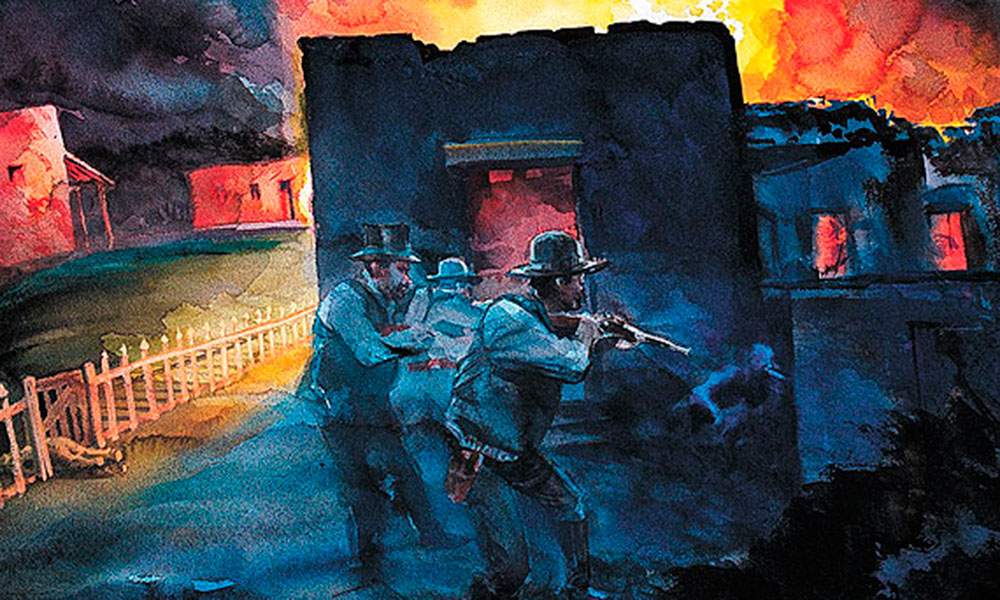

Sergeant Philbrook was shot at Fort Union, for the attempt upon Lieut. Gray’s life. At the time of the execution there were three Apaches and a Mexican confined in the guard house, on what charge I [a civilian named John Riley] did not learn, but it appears that someone passed the window where they were looking out, and told them they would be shot next and when the guard opened the door, supposing their time had come, they fired on the guard, with their bows and arrows which had by some oversight been left with them, wounding several, which so enraged the guard that they closed the door and seized some shells, which were lying near, and lighted two, which they tossed into the room, through an aperture over the door. Then the room was opened a short time after, all that remained was a few remnants of arms, legs, and skulls.

Scott and I already knew about the Philbrook execution. On March 13, 1862, while waiting for the rest of the 1st Colorado Volunteers to catch up, Sgt. Darius A. Philbrook had become drunk at the sutler’s store and turned disorderly. When Lt. Isaac Gray ordered him to stand down, the sergeant drew his pistol, fired at the lieutenant and wounded, but did not kill, him with a bullet between the eyes. Philbrook’s execution was carried out at Fort Union on April 8, in the wake of the Battle of Glorieta Pass and while the Colorado Volunteers were chasing Henry Sibley’s brigade toward the Texas border.

We had dismissed Sgt. Philbrook as a potential “victim” because he was five feet six inches tall, and none of the men in the grave matched that height. The newspaper article, however, gave us a lead on the other victims. All of the trauma on our victims’ bones were fully consistent with blast trauma given off by the “shells,” which were probably artillery shells or, less likely, a hand grenade. This article certainly explains the piece of “shrapnel” found imbedded in one man’s knee.

As to the apparent coup de graces? We speculate that the soldiers guarding the prisoners had just witnessed the coup de grace administered after the execution of Philbrook. The prisoners were probably suffering greatly from the explosion in their cell. The soldiers or the captain of the guard “mercifully” administered a coup de grace to the mortally wounded Apaches and the “Mexican” prisoner.

Who was this “Mexican?” The prisoner log for Fort Union indicates that New Mexico Volunteer Miguel Lucero was arrested for drunkenness on December 24, 1861. He escaped from the fort garrison in January, but was captured and reconfined. He was still in the garrison on April 1. His service record ends in April. We have no record of his release from the garrison, his discharge or another method of leaving the New Mexico Volunteers. As someone who had “deserted” by escaping the jail, his “accidental” death during the escape of the three Apaches could have been considered just deserts by the Army.

Was this, then, a case of murder?

The Apaches and the U.S. Army, assisted by the New Mexico Volunteers, were at a state of war in 1862. Dispatches in the months before April 1862 indicated that Apaches had stolen livestock from settlers near Fort Union, and that troops detained warriors for questioning about these activities. Later, orders would be issued to kill adult male Apaches on sight, as was common during wartime. Furthermore, the prisoner Lucero had been known to escape his jail sentence once. Some commanders in the Eastern Theater of the Civil War were beginning to execute repeat deserters without trials.

Furthermore, in the wake of the Battle of Glorieta Pass, the command of Fort Union had just been changed: Col. Gabriel R. Paul, 4th New Mexico Volunteers, turned command of Fort Union over to Capt. Asa B. Carey, 13th U. S. Infantry, on April 6. In addition, the commander of the Colorado Volunteers, Col. John P. Slough, resigned on April 9, in favor of Col. John M. Chivington. No communications or orders were issued between April 6 and April 17 while Capt. Carey adjusted to his new command. During that time, on April 8, the attempted escape and unauthorized execution of the prisoners occurred.

Was it murder? An accident? Or were these men the casualties of a war crime committed during the Civil War in the aftermath of the Battle of Glorieta Pass? You be the judge.

Both retired archaeologists from the National Park Service, Catherine Holder Spude writes nonfiction history from her home in Santa Fe, New Mexico, while Douglas D. Scott conducts archaeological and forensic consulting and lives in Grand Junction, Colorado.

Photo Gallery

– True West Archives –

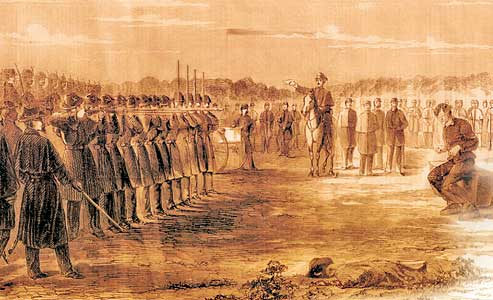

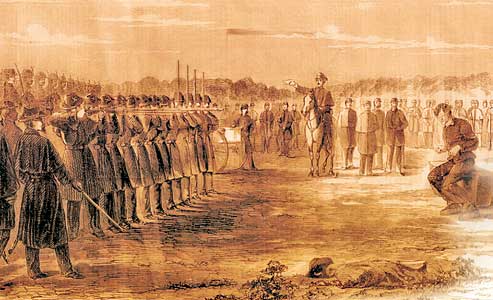

– Illustrated in Harper’s Weekly, December 28, 1861 –

– True West Archives –