“Our house at Fort Lincoln, Dakota” is a notation that many may not pay much attention to, other than as an identification of a depicted location.

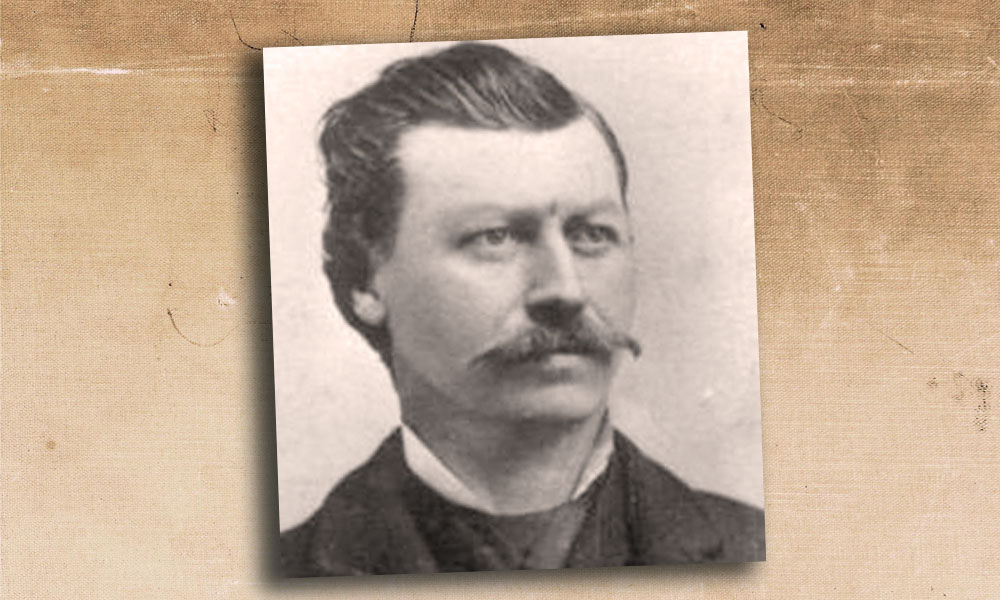

It was written by Gen. George A. Custer, on the verso of his own portrait of him and the 7th Cavalry officers under his command, along with their wives and some infantrymen, which sold at Swann Galleries in New York City on February 11 for a $20,000 bid.

Auctioned off as part of the signed historical photographs from the Jerome Shochet Collection, this photograph taken by post photographer Orlando S. Goff (based in nearby Bismarck) is a treasure upon first impression. Along with the verso note, it was signed twice by “G.A.C.” and inked with the names of each person in the photograph.

Yet that house in the background has its own story to share.

George’s wife Libbie would first glimpse the house on November 16, 1873, the day she arrived at the fort, along with her husband George and his sister Margaret, who was married to George’s first lieutenant James Calhoun. It’s quite possible that Goff took this photo on that same day, when the regiment band welcomed the commander and his family by playing the 7th Cavalry’s battle march, the quick-step tune of “Garry Owen.”

“After four months spent in Michigan when Sister Maggie and I got here, we found this one of the largest Posts in the country, and our houses, substantial, wooden, all ready for us, all ready for housekeeping, made so by our husbands,” Libbie wrote to Aunt Eliza in March 1874.

That house would become Libbie’s full-time occupation, as the letter further shows: “You see, Aunt Eliza, it cost the Government so much to send our Regiment up here from the South, we think this will be our home for years to come. So I thought I would take pains to give it a permanent character. So for three months I kept painters and carpenters at work steadily. We curtained about twenty windows, carpeted almost all of the floors, and we had made a beautiful billiard-room with rented billiard-table…. This being the home of the Commanding officer it is much the largest, more entertaining being done here than in all the others put together.”

Yet the next line she wrote was the most surprising of all: “Well, about a month since, in February, the house was burned to the ground….”

Not only was Goff responsible for taking some of the last-known photographs of George A. Custer, he took the last-known photographs of this short-lived house! (You can see more of the house in other Goff photos.)

Libbie would go on to write that the “blaze had started in the attic” due to a “carelessly built, ill-pointed chimney in close proximity to the coal-oiled paper linings of the walls.”

Libbie was right in presuming Fort Abraham Lincoln would be the Custer home for “years to come.” In fact, the field headquarters was the last place she would make a home with her husband.<

Of course, another home was quickly built for the commander and his wife. In that home, she would find herself comforting the wives, after hearing the distressful news that Lakotas had compelled U.S. Army soldiers to retreat on June 17, 1876, in what would become known as the Battle of the Rosebud.

On Sunday, June 25, while her husband George and his men were perishing on a Montana battlefield, Libbie found herself at her home with the women. They were all trying to console themselves by singing hymns, while one of them “sat dejected at the piano and struck soft chords that melted into the notes of the voices…. The words of the hymn, ‘E’en though a cross it be, Nearer, my God, to Thee,’ came forth with almost a sob from every throat,” wrote Libbie in her 1885 memoir, Boots and Saddles, Or Life in Dakota with General Custer.

The news of the deaths of their husbands would not reach the wives until the day after the Fourth of July. “This battle wrecked the lives of twenty-six women at Fort Lincoln, and orphaned children of officers and soldiers joined their cry to that of their bereaved mothers,” Libbie wrote. “From that time the life went out of the hearts of the ‘women who weep,’ and God asked them to walk on alone and in the shadow.”

The last memories of her husband were made while Libbie rode beside him, accompanying him out of camp, that May. Behind them rode roughly 1,200 men and 1,700 animals. They first rode through Indian quarters, filled with the “moaning” of a “minor tune that had been uttered on the going out of Indian warriors since time immemorial.” Then they passed Laundress Row, where the “wives and children of the soldiers lined the road” and “Mothers, with streaming eyes, held their little ones out at arms-length for one last look at the departing father.” When the band struck up “The Girl I Left Behind Me,” she wrote, “The first note made them disappear to fight out alone their trouble….”

Those first notes betrayed the words behind them: “The hours sad, I left a maid, A lingering farewell taking. Whose sighs and tears my steps delayed. I thought her heart was breaking.”

Libbie would stay at camp with her husband that first night and bid him farewell in the morning. She would, sadly, become that girl in the song: “In hurried words her name I blest, I breathed the vows that bind me; And to my heart in anguish pressed, The girl I left behind me.”

The Jerome Shochet Collection hammered in at nearly $360,000.