When Frank Butler loaded his guns at a fairground outside Cincinnati, Ohio, one spring day in 1881, the last thing in his thoughts was a legend about to be born.

When Frank Butler loaded his guns at a fairground outside Cincinnati, Ohio, one spring day in 1881, the last thing in his thoughts was a legend about to be born.

A professional exhibition shooter who counted himself among the best in the country, Butler was prepared to outshoot all comers and make some money.

Instead, he was beaten by the local favorite, a 21-year-old slip of a girl. Annie Mozee, as she called herself at the time, would soon explode into superstardom and become the embodiment of the best qualities of pioneer women—courage, endurance, truthfulness, grace and, above all, an unerring aim with rifle, shotgun or pistol. Annie Oakley had just challenged destiny with blackpowder and lead.

Ironically, Oakley probably seldom visited the West during her long career. Yet, as part of Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West—the great impresario’s creation to educate Easterners and Europeans about the taming of the frontier—her qualities eclipsed even those of the famed scout and buffalo hunter.

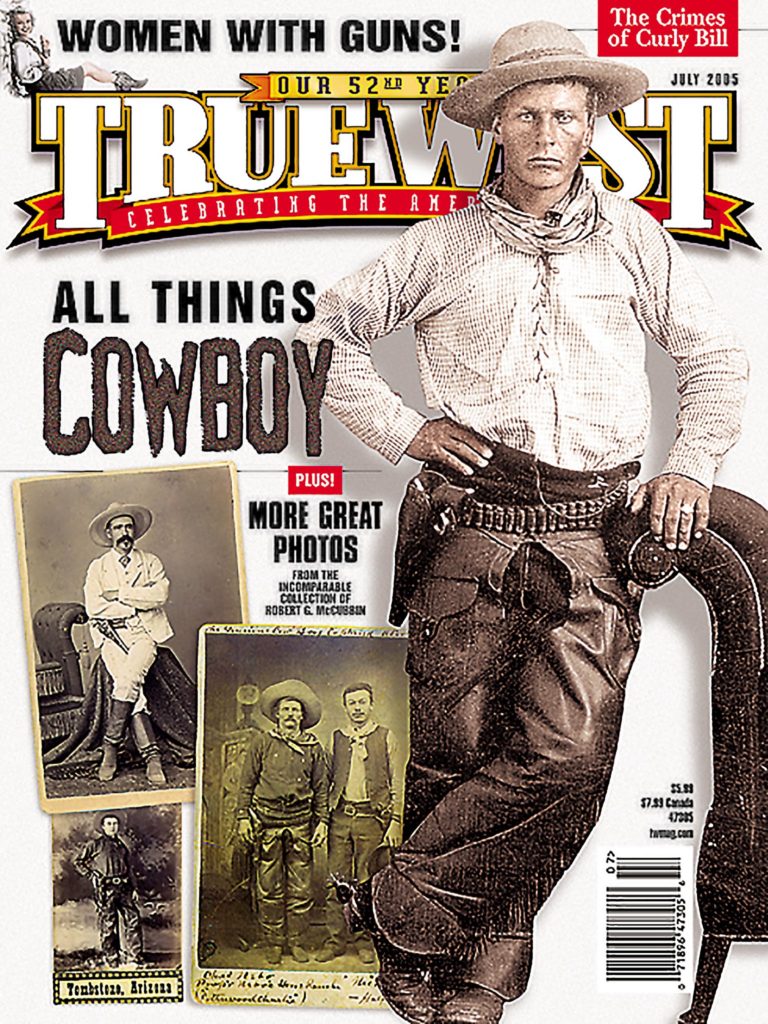

The story of the West was emerging slowly. Without the movies and TV shows we take for granted now, without even the means to mass-distribute the photographs that were being produced, putting live heroes of the West in Eastern theatres was a way to get the message out. Wild Bill Hickok, Cody and the others didn’t just talk about their adventures; they demonstrated their prowess with gun, rope, knife and whip. It was “edutainment,” and it grew so big that, when the stage could no longer contain it, the spectacle moved to arenas, where buffalo were “hunted,” cattle were roped and stagecoaches were robbed and then rescued.

History and newspaper accounts being mostly written by men at the time, the role of women was generally overlooked. In fact, it is only recently that the journals and diaries of the West’s women have been brought to light by authors such as Joanna L. Stratton in her Pioneer Women: Voices from the Kansas Frontier. These reveal women encountering the same dangers, overcoming the same obstacles and accomplishing the same tasks as the men—and more besides. (So extensive is the emerging story of women that in describing just their experience with firearms, the first draft of my book Silk and Steel: Women at Arms ran over 250,000 words before being edited to a publishable length.)

One contemporary form of journalism did recognize women. Comic almanacs, published from the mid-1830-50s, were illustrated with cartoon drawings that paid tribute to hardy, American frontier women. The popularity of these unabashedly tall tales in the East and England attracted hoards of immigrants to the West.

Sensational female hunters

From 1841-66, some 350,000 women and men traveled the 2,400 miles by wagon from the Missouri River to California and Oregon.

One of the women was Martha Maxwell, the “Colorado Huntress.” Considered by many to be the founder of modern taxidermy, she was America’s premiere female naturalist. She hunted North American game, such as elk, deer, mountain lion and bighorn sheep, and caused a sensation at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition of 1876 with her displays of mounted animals in natural poses within their habitats.

Long familiar with firearms, she was just 10 when she shot a rattlesnake about to strike her 4-year-old sister. She emigrated to Colorado in 1860 with her lumberman husband James Maxwell. She became his hunting companion and learned the art of taxidermy, long a male occupation. Her discovery of the Rocky Mountain screech owl as a distinct species led to its name of Scops Maxwelae in her honor.

A name that blazes through Western lore is Martha “Calamity Jane” Cannary. In 1865, the 13 year old traveled five months by wagon train to Montana with her family. Her parents died soon after, and Jane took her brothers and sisters to Wyoming Territory.

Already an accomplished hunter and rider, she eventually went east to appear on stage, and it’s possible she toured briefly with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. Years later, when Jane heard that Wild Bill Hickok (her supposed paramour) had been murdered, she reportedly confronted his killer with a meat cleaver and held him until his arrest.

Ella Elger married Texas Ranger J.T. Bird in 1877, and one of the gifts she received from her new husband was an inscribed Winchester Model 1873 rifle that had been presented to the celebrated lawman by the Texas legislature. She practiced with it daily, taking the heads off prairie dogs. Twice she killed a buffalo with one shot, and she claimed to have killed three wild turkeys with a single round. Her skill was necessary, as she was often left home alone even while Comanches were marauding. After her husband died during an 1888 blizzard, the Winchester helped her keep meat on the table, and she used the skins to make gauntlets and vests for cattlemen in the area.

The young, attractive widow’s reputation with the rifle kept unwanted suitors away. When a cowboy rode up to her place, she’d walk out with the Winchester at her shoulder and say, “Keep riding.” He did. One local said he’d “rather any man in Cottle County would shoot at me than Mrs. Bird.” In 1934, Ella presented the rifle to the Panhandle Plains Historical Museum at Texas A&M University.

Bandidas worth their salt

Anna Emmaline McDoulet and Jennie Stevens were children of hard-working and honest parents, but each had a wild streak and became co-conspirators in a two-year hellraising spree. They ran for awhile with the Doolin-Dalton Gang but then decided to work on their own, selling whiskey to the Indians and stealing horses. They often wore men’s clothes during night raids—confusing the law and keeping their identities secret. Stevens, a.k.a. Little Breeches, was arrested in mid-August 1895, but she stole the sheriff’s horse and made her getaway. The next night, she and McDoulet, a.k.a. Cattle Annie, were captured by two marshals. Both girls were tried and sentenced to a women’s reformatory in Framingham, Massachusetts. Released after short sentences, their subsequent history is vague—giving all the more power to the legend they created in two brief years of crime.

Mary Fields, a slave born in Tennessee in 1832, traveled to Ohio after the Civil War and worked for the Ursaline convent in Toledo. Following her friend Sister Amadeus to Montana, Fields helped build the St. Peter’s Mission school. An imposing six feet and 200 pounds, Fields drove a team of horses and was no stranger to gun handling. She kept a Smith & Wesson revolver tucked under her apron, and she also owned a Winchester Model 1876 carbine. The nuns tolerated her unladylike behavior, but the bishop didn’t, and she was forced to leave the mission.

Fields moved to Cascade, Montana, where she eventually received a government contract to deliver the mail, becoming the second woman and first black woman to work for the U.S. Postal Service. Cascade held Stagecoach Mary (as she was known) in great affection, and for a number of years, its citizens celebrated her birthdays (two of them, since she was uncertain when she had been born) as holidays. She died in 1914.

Lillian Frances Smith, the Indian Princess Wenona, was born in 1871 in Coleville, California. Before she was 10, she proved proficient with rifle, shotgun and pistol, winning so many local turkey matches that organizers asked her to stop competing so others (mostly boys and men) could have a chance. Before reaching her teens, she was a seasoned exhibition shooter. In 1885, just 14, she joined Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and was given top billing for the 1886 season as “California Huntress, Champion Girl Rifle Shot.” Smith toured with the show to England during Queen Victoria’s jubilee year in 1887.

When she fell into the shadow of another Wild West performer, Annie Oakley, a bitter rivalry followed. Smith never exuded the grace and charisma Oakley had in front of an audience. Plump, ill-spoken and sometimes surly when she wasn’t shooting well, she also showed unforgivable poor sportsmanship when shooting in the field in England. Oakley left the show after the London tour, probably due in part to her rivalry with Smith. When Oakley returned in 1888, it was Smith who moved on, possibly a condition Oakley had negotiated.

Smith continued shooting with other shows before she died in Oklahoma in 1930. Buffalo Bill Cody’s standing offer of $10,000 to anyone who could best her was never successfully challenged. Some of her unbroken records include: breaking 20 swinging balls in 12 seconds; 300 swinging balls in 14.33 minutes; and 71 of 72 thrown balls while on horseback.

Following their forebears

Many women living well after the pioneer era embody the spirit, tenacity, courage and outdoor skills of their forebears, often becoming legends and role models in their own right. They encompass modern-day hunters, ranchers, writers, artists, actors, singers and models.

Annie Bianco-Ellett, who began her career as a fashion model and barrel-racing rodeo performer, promotes Colt firearms and the American Western Firearms Company, and she’s a spokesperson for the Cowboy Mounted Shooting Association (CMSA). She has her own clothing, holster and boot line, and teaches mounted shooting in Cave Creek, Arizona.

An entertainer-turned-emblem of American Western women is the late Dale Evans. Born Lucille Wood Smith in 1912 in Uvalde, Texas, she survived difficult early years to become a singer (changing her name in the process) and film actor. Her first major Western was The Cowboy and the Senorita. Her agent had exaggerated her Texas upbringing, and she learned riding and roping on the set, enduring bruises and indignities in the process. The film introduced her to Roy Rogers, who she married on New Year’s Eve in 1946.

Dale and Roy appeared together in films, radio and television, and recorded over 400 songs. Dale composed their well known theme song “Happy Trails” just 40 minutes before a show, teaching it to Roy and the Sons of the Pioneers with minutes to spare (the title came from a message Roy customarily put in his autographs). The couple cofounded the Roy Rogers-Dale Evans Museum in Victorville, California (now in Branson, Missouri), and had been married 50 years when Roy died in 1998. Three years later, in 2001, Dale was buried beside her husband at their ranch—a remarkable woman and a true “Queen of the West.”

Paying tribute to female icons

The roll call is long for the icons of Western womanhood. The National Cowgirl Museum and Hall of Fame, established in 1975 to honor them, has inducted some 172 into its ranks. Other Western museums have paid homage to female icons with permanent displays and special exhibits. It’s likely that most of these women were proficient with firearms.

Any accurate account of the winning of the West and the preservation of its spirit must include these remarkable and unique women, who were real pioneers no matter what time period they graced.

R.L. (Larry) Wilson is the author of 45 books and nearly 300 articles. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West (cowritten with Greg Martin) and The Peacemakers were awarded Wranglers. Wilson is a former curator of firearms for the Wadsworth Atheneum and employee of Colt in Hartford, Connecticut. This article is adapted from Silk and Steel: Women at Arms. Signed copies are available at a special True West price of $55 postpaid; limited leather editions: $175 postpaid. Credit card orders: 866-278-2888; send check or money orders to: 1730 Kearny St., G-1 San Francisco, CA 94133.