“Brethren and sisters, what I have said, I know to be true.”

“Brethren and sisters, what I have said, I know to be true.”

Levi Savage was a lone voice that hot August morning in 1856 as he graphically warned 500 of his fellow Latter-day Saints about the hazards of continuing their journey to the Mormon mecca of Salt Lake City, Utah.

The trail-wise Savage shared the burning religious fervor with the others who were emigrating, not in the traditional covered wagon, but by pushing and pulling handcarts loaded with supplies and all their worldly belongings. Yet, he knew the dangers and suffering likely to befall Capt. James Willie’s handcart company if it headed out so late in the season. After all, it was already August 11, and they had only reached the town of Florence in the Nebraska Territory—a mighty trek all on its own, considering most of these recent converts to the Mormon Church had started out in May aboard ships from their homelands in Scandinavia, England and Scotland. Even with luck, it was likely they wouldn’t reach their destination until late October, and by then the mountain regions between Florence and Salt Lake City would be snow-shrouded.

Savage was convinced they should winter in the Midwest and leave the next spring. But as he surveyed his companions—less than 100 able-bodied men and the rest children, women or the aged—he knew their zeal eclipsed his warning. After staunchly voting against setting out, he nevertheless allied himself with his friends.

“I will go with you,” he asserted, “will work with you, will rest with you, will suffer with you, and if necessary I will die with you.”

Fortunately, Savage’s destiny would not include dying along the Mormon Trail. Sadly, that would not be the case for many of his companions.

Willie’s company would become part of the greatest emigrant disaster in the history of the West. Afterwards, the very word “handcart” was forever shrouded in sorrow.

“Let them come on foot”

Thousands of Saints had followed the Mormon Trail since the founding of Salt Lake City in 1847. A communal fund had been set aside for emigrant loans to cover the expenses of their wagon trains. But in the summer of 1855, a grasshopper infestation wiped out many of Utah’s crops. Then followed an unusually severe winter, which took its toll on the weakened farm animals. Donations to the fund plummeted.

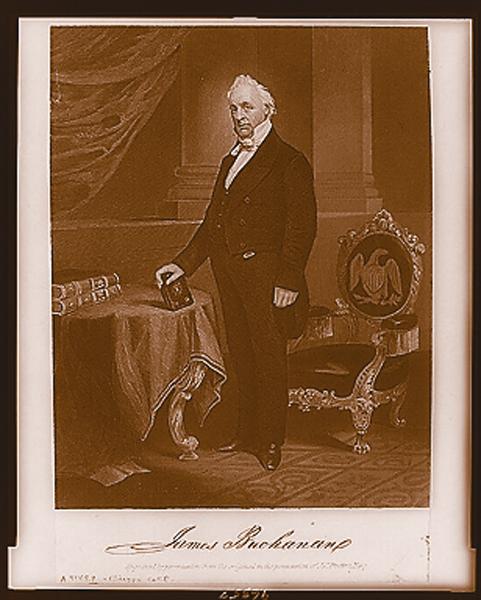

Mormon leader Brigham Young was faced with a dilemma. Thousands of the newly converted were eager to join his gathering. Yet, there wasn’t enough money to outfit them with wagons and oxen. In response, Young rekindled an idea he had originally voiced four years earlier: If gold seekers could walk to California with their belongings on their backs or in wheelbarrows, “then Saints seeking a higher god than gold ought to be able to do so as well.”

In an October 1855 Epistle to the Saints, Young turned the idea into a challenge. “Let them come on foot, with handcarts or wheelbarrows,” he proclaimed. “Let them gird up their loins and walk through, and nothing shall hinder or stay them.”

The first summer, three companies of more than 800 people mustered their resources and walked to their promised land. Each company was greeted in Salt Lake City with a festival of joy and praise.

But in 1856, there was plenty to hinder the foreign emigrants. And it started at the beginning.

Mormon missionaries had been successful in appealing to new converts in Europe. Thousands—working people and the poor—swarmed to the docks in Liverpool in May 1856 to begin their journey to the “new Zion,” but stormy weather delayed their ships. By early June, when they should have been setting out across the Missouri plains, hundreds of Mormons and two of their four ships were still thousands of miles away.

Their luck didn’t improve when they reached America. According to plan, they boarded the Rock Island Line train in New York City and rode it to its terminus in Iowa City. When they arrived, they were shocked to find that hundreds of handcarts were yet to be built due to a scarcity of seasoned lumber and labor. The Mormons remained in Iowa City for weeks as their own craftsmen helped build the carts.

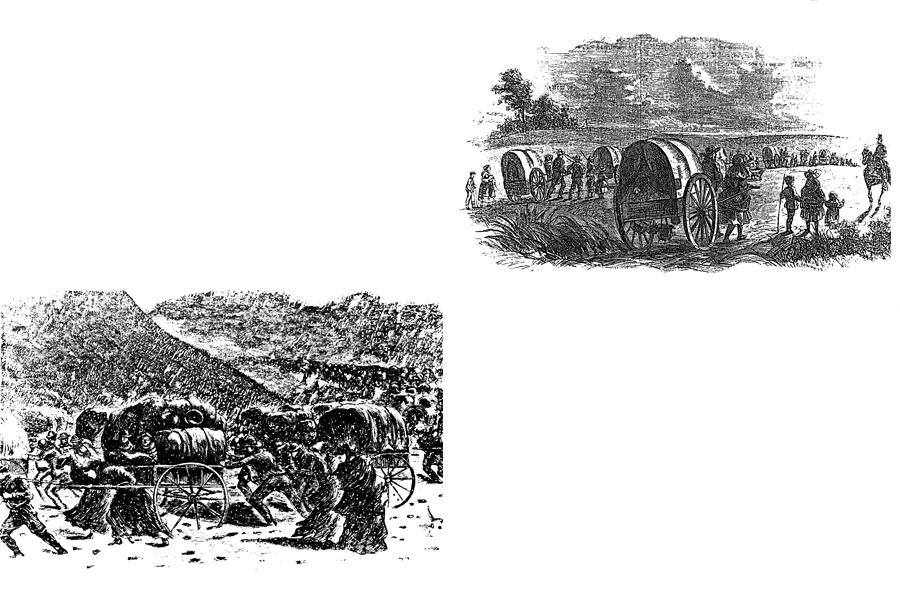

Boxes on wheels

As they waited, curious emigrants inspected the handcarts they were expected to transport across 1,300 miles of wilderness to Salt Lake City. Some were boxes on wheels, while larger “family carts” sported hooped tops such as those on covered wagons. Side rails extended in the front and were connected by a crossbar. The back rim of the cart was smooth so those behind could push. Originally, many cart boxes were intended to rest on iron axles and wheel rims. Due to sparse materials and time pressures, however, the axles and even the wheels were often crafted from unseasoned wood.

At last, some of the pilgrims were ready to begin their journey. They divided into smaller companies, each led by a returning missionary who was familiar with the trek. The first two groups, headed by Edmund Ellsworth and Daniel McArthur, pulled out during the second week of June. Despite the lateness of their start and the obvious rigors ahead, their spirits were high. In the evenings, they sang and danced to the Birmingham Band, whose members had also joined the emigration.

The singing and dancing wouldn’t last. As they tugged their carts across the arid prairie, the unseasoned wood began to warp. The sand slowly ground down the unprotected wooden wheels and axles, leaving them wobbly and difficult to push. The already strenuous ordeal became even more demanding.

Week by week, the exhausted pilgrims slogged past well-known landmarks—the forks of the Platte River, Chimney Rock, Scotts Bluff. Like the oxen they had replaced, the emigrants humbly lowered their heads and pushed, or pulled, their burdens. Along the way, they sometimes had to bury some of their members.

Despite fatigue, short rations, the scorching sun and rickety handcarts, the Ellsworth company trudged into Salt Lake City on September 26. The city’s entire population swarmed to welcome the “foot soldiers of Zion.” The welcomers sang and broke open melons to cool the travelers’ parched lips. Before the celebration had faded, the McArthur company plodded in, and the festivities were revived.

With Brigham Young’s personal greetings and Capt. Pitt’s brass band’s music filling the air, many likely proclaimed the handcart concept a roaring success. When the third company, under Edward Bunker, arrived a week later, the Saints again broke open the melons and fired up the band. Bunker’s assistant David Grant predicted that “the Saints would be crossing with handcarts for years to come.”

An astonished Brigham Young

No one—especially Brigham Young—realized 1,461 pilgrims were still on the way. Besides the 500 with Capt. James Willie, another 576 souls were pushing handcarts under Capt. Edward Martin. And behind them were two smaller wagon trains with 385 emigrants under W.B. Hodgett and John Hunt.

Brother Young was shocked when he finally learned, two months later, that those people were still on the trail. He had thought the year’s emigration was over. Apparently, so did the first three companies that had arrived to such fanfare. No one was aware that the Willie and Martin companies had even considered forging ahead on the late-season trip.

Capt. Willie’s company had departed Iowa City on July 15. The even larger Martin company crept out on July 26. Behind them came the smaller wagon trains. Despite the delayed start, the first three weeks were uneventful as the companies slowly advanced toward the Missouri River. By August 11, they were camping by the river in Florence, Nebraska, where the hot weather made Savage’s warnings of cold and disaster seem unbelievable. The Willie company left Florence on August 18; the Martin company on August 25. The wagon trains finally pulled out on September 2.

It took considerable brawn and determination for the emigrants to move their handcarts along. Most handcarts, which weighed about 60 pounds empty, were designed to accommodate five people. Each emigrant was limited to 17 pounds of personal belongings, adding 85 pounds to the weight. Each cart was also obliged to carry a 98-pound sack of flour. Often, there were small children or infirm elderly who had to ride. And there were never enough able-bodied men and boys to push all the carts; many were moved by women and girls.

Disaster

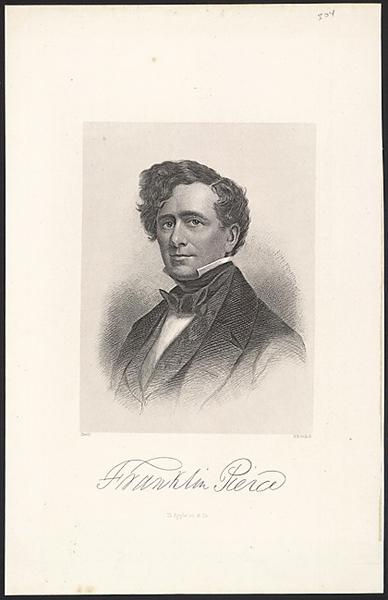

Franklin Richards, president of the Saints’ European Mission, overtook the Willie and Martin companies while returning from England. He visited with each for a while, then he and several other high-ranking Mormon elders passed them en route to Salt Lake City. He noted that he was confident they would arrive safely, “though they may experience some cold.” Richards ended up informing an astonished Brigham Young that these people were still on their way. But that news wouldn’t reach the leader’s ears until October 4. By then, disaster had already struck.

On the trail, the exhausted pilgrims fought against the calendar as the inevitable hazards of late fall travel lurked ahead. But the Mormons pushed on, averaging 15 miles a day.

At Wood River, a buffalo herd stampeded through Willie company’s camp. No one was hurt, but most of the cattle the emigrants had brought along for food bolted and vanished.

By October 1, the Willie company finally reached Fort Laramie, which had long been a source of fresh supplies. At that late date, however, the fort was out of flour and could offer only a couple of cracker barrels. With a grim understanding of their predicament, and 700 miles yet to go, Capt. Willie cut the company’s flour ration.

Day by day, their strength waned. The wobbly handcarts became life-sapping burdens. Desperate to save weight, the Mormons threw away most of their belongings, including much of their bedding and heavy clothing, despite the daily drop in temperature. Nearly exhausted, the Mormons trudged past Independence Rock, then waded across the bone-chilling Sweetwater River. As the icy water engulfed them, some of the newly converted Saints began to question whether Young’s handcart scheme was indeed “God’s Plan.”

“The chill which it [icy water] sent through our systems drove out of our minds all holy and devout aspirations and left a void, a sadness,” John Chislett later noted.

Throughout the next few weeks, that void overflowed with the dangers and suffering that Savage had predicted. As the temperature continued to drop, so did the emigrants’ spirits.

Chislett’s recollections paint a grim picture of Willie’s group. The frigid weather, teamed with exhaustion and dysentery, began to take the life of one poor soul after another. “Life went out as smoothly as a lamp ceases to burn when the oil is gone,” he wrote.

“At first the deaths occurred slowly and irregularly,” he continued, “but in a few days at more frequent intervals, until we soon thought it unusual to leave our campground without burying one or more persons.” He watched helplessly as “many a father pulled his cart with his little children on it until the day preceding his death.”

And every death weakened the company further. Chislett was in charge of a group of 100 Saints and by the end, he noted, “I could not raise enough men to pitch a tent when we camped.”

Eighteen-year-old Sarah James would write that she was “cold all the time. There was either rain or snow or wind. Even when you wrapped up in a blanket your teeth chattered.”

Last rations of flour

In early October, Capt. Willie issued the last rations of flour. “We traveled on,” Chislett noted, “in misery and sorrow.” Mid-October brought additional blinding flurries of sleet and snow. The dispirited emigrants sadly recalled the piles of warm clothing they had left behind to lighten their loads.

The Martin company was almost 100 miles behind Willie’s outfit. As its freezing members gazed dejectedly at the last crossing of the Platte River, they too reflected on their decision to discard most of their protective clothing. Yet, they summoned their remaining strength and bravely waded into chest-deep water, pushing aside drifting chunks of slushy ice. By late October, total fatigue, sickness and severe frostbite had mutated “God’s plan” into “Satan’s nightmare.”

Martin company member Patience Loader wrote about the misery and loss: “When we was in the middle of the river, I saw a poor brother carrying his child on his back and he fell down in the water. I never knew if he was drowned or not. I fealt sorrey that we could not help him, but we had all we could do to save ourselves from drowning. After we got out of the water, we had to travel in our wett cloths until we got to camp and our clothing was frozen on us.”

Back in Salt Lake City, the architect of the handcart plan now became the savior of those still on the trail. When he heard about these other pilgrims, Young called an emergency meeting to marshal a massive rescue. After dismal weeks of searching through pelting blizzards, the rescue teams eventually located the pitiful, frostbitten survivors.

The number of dead has never been firmly settled, but historians say the Willie company lost from 62 to 77 pilgrims before the surviving members arrived in Salt Lake City on November 9. As many as 150 members of the Martin company never saw their new Zion. The survivors arrived on November 30. And the last wagon trains came in as December was beginning.

Besides the dead, scores more were permanently maimed by the freezing cold. Families in Salt Lake City took the refugees into their homes, feeding and nursing them until they recovered.

As the years rolled by, the abandoned handcarts strewn along the trail slowly disintegrated. Their splintered skeletons bore testimony to future pioneers that potential tragedy lurked in the new frontier. When the country matured and sprouted cities and roads along the Mormon Trail, the images of this ill-fated expedition began to fade into the history books.

Those books, however, could never fully portray the unthinkable sacrifices made by the 1856 “foot soldiers of Zion” with their handcarts and heartaches.

Dennis Goodwin is a freelance writer specializing in the early American West. He lives with his family in Snellville, Georgia.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Merrill Library Special Collections & Archives of Utah State University –

– All images courtesy Harold Warp Pioneer Village in Minden, Nebraska, unless otherwise noted –