Nearly two dozen Texas gunmen rode a specially outfitted railroad car into Casper, Wyoming, on April 5, 1892.

Nearly two dozen Texas gunmen rode a specially outfitted railroad car into Casper, Wyoming, on April 5, 1892.

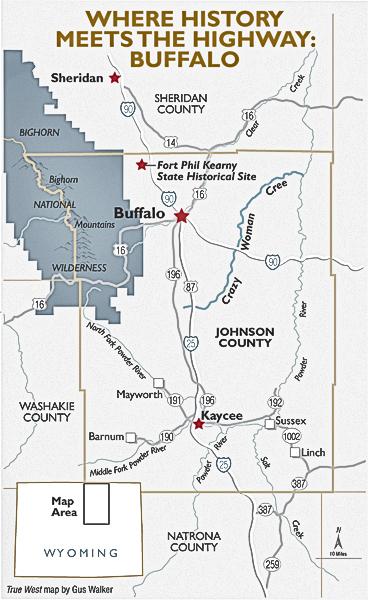

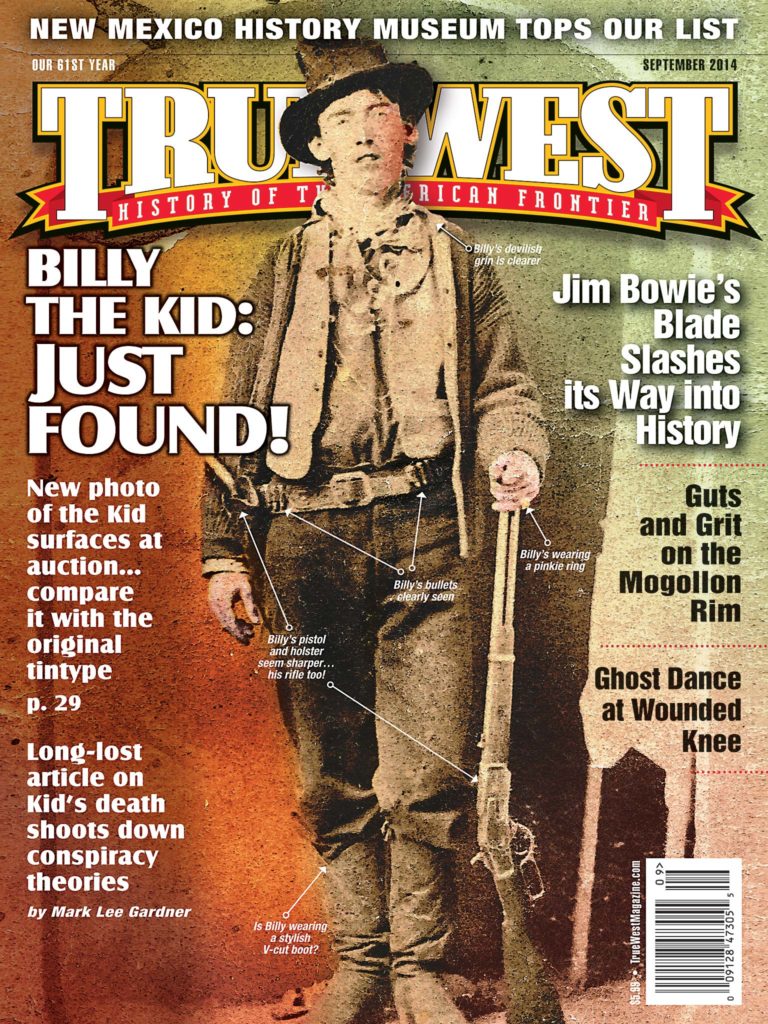

They disembarked well before sunrise, along with 30 or so cohorts—cattle barons, local politicians and even a couple of newspaper reporters. Well-armed and toting a “Death List,” the mob rode north toward Buffalo, cutting telegraph lines to keep their invasion a secret. The Johnson County War had begun.

Their mission, organized and paid for by the Wyoming Stock Growers Association, was simple—kill all 70 or so of the men on their hit list between Casper and Buffalo, under the pretense of restoring law and order to Johnson County. The hired guns had been told they were after thieves and rustlers, and had been promised $5 a day, plus a $50 bonus for every “outlaw” they killed.

While it’s true that some folks in the northern Wyoming area had a somewhat casual attitude toward the law, there was a lot more to the War than ranchers taking on a few rustlers. Patty Myers, former president of the Wyoming Historical Society, cited a number of factors that led up to the War—several bad winters and a weak stock market had investors shying away from the big cattle operations. But what really steamed the WSGA was that more and more small ranchers, inspired by the Homestead Acts, were moving into the area and grazing their cattle on the open range land that the rich and politically well-connected men in the Stock Growers Association had come to regard as their own personal domains. By the spring of 1892, they’d had enough.

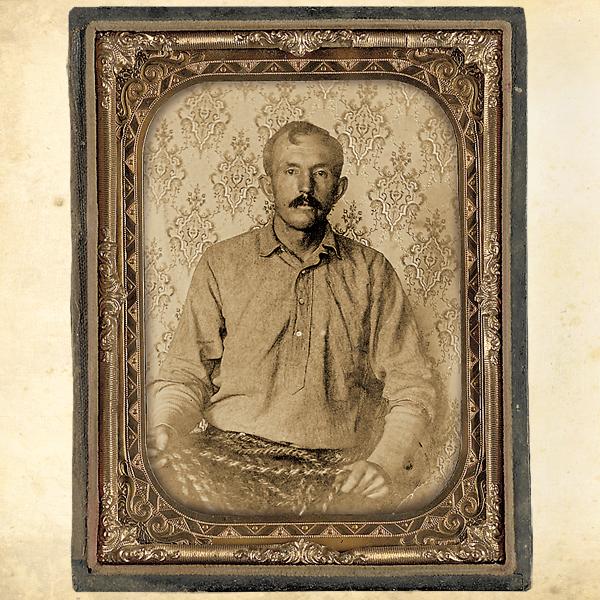

The Invaders (also called the “Regulators”) headed for the KC Ranch, where they’d heard a bunch of rustlers had holed up. On arrival, though, they found just four men. They captured two, but killed Nick Ray and Nate Champion.

Then they headed for Buffalo, which they regarded as a hotbed of renegades and rustlers. But by the time they stopped at the TA Ranch a few miles south of town, the people of Buffalo had gotten wind of the invasion and mounted a counterforce, which surrounded the Invaders and demanded their surrender.

One man escaped the siege and got word to Governor Amos Barber, who was sympathetic to the WSGA. Fortunately for the Invaders, the telegraph lines they’d cut had been repaired and Barber sent a desperate telegram to President Benjamin Harrison: “An insurrection exists in Johnson County. … I apply to you on behalf of the state of Wyoming to direct the United States troops at Ft. McKinney to assist in suppressing the insurrection.”

The Invaders surrendered to the federal troops, but you can still see bullet holes from the siege in the old barn at the ranch. Although they were defeated in Buffalo, the Stock Growers had enough political clout to make sure none of the group ever faced trial.

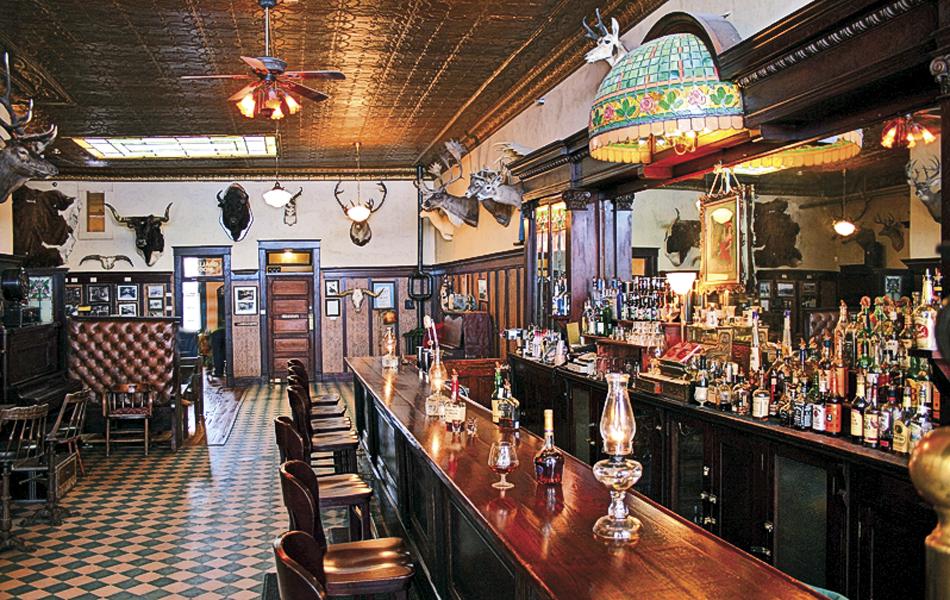

Buffalo was founded in 1879, on a buffalo trail that forded a tributary of the Powder River. Today the town, nestled at the base of the scenic Big Horn Mountains, serves as the seat of Johnson County. Historically minded visitors will want to stay at the Occidental Hotel. Furnished throughout with antiques, the venerable hotel still reflects the splendor of the 1880s. Author Owen Wister spent many an evening relaxing in the saloon of the hotel, and based many of the characters in his classic Western novel, The Virginian, on people he’d met there.

John Stanley, the Arizona Wildlife Federation’s 2007 Conservation Media Champion, is a former travel reporter and photographer for The Arizona Republic.

Photo Gallery

– Photo by Stuart Rosebrook –

– Courtesy The Occidental Hotel –

– Courtesy True West Archives –