William Quantrill addressed his ragtag army on the evening of August 20, 1863. “Boys, this is a hazardous ride, and there is a chance we will all be annihilated.”

William Quantrill addressed his ragtag army on the evening of August 20, 1863. “Boys, this is a hazardous ride, and there is a chance we will all be annihilated.”

A few men slunk away, but the rest rode through the night with their 25-year-old commander. Their mission—vengeance.

Not long before, military commander Thomas Ewing Jr. had taken several of Quantrill’s female relatives prisoner, housing them in a makeshift jail. On August 14 the building collapsed, killing five and injuring several others. Quantrill, convinced the deaths were no accident, was livid.

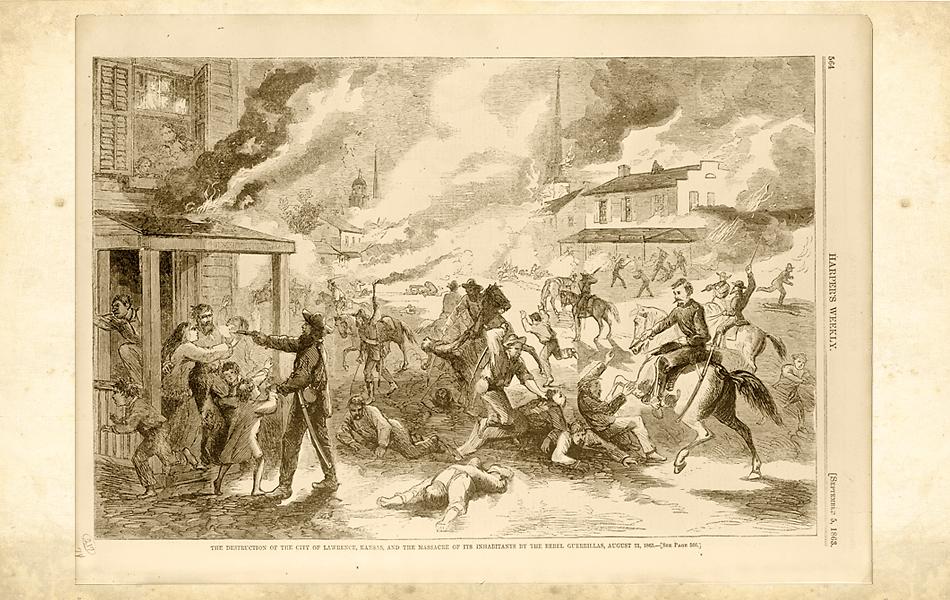

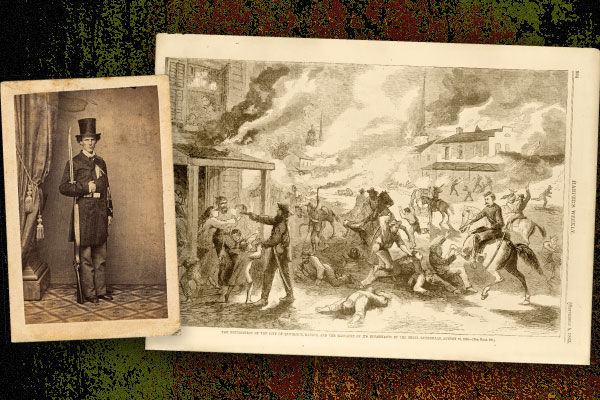

Shortly after sunrise on August 21, the mob of nearly 450 men reached Lawrence. After smashing a camp of the 14th Kansas Regiment, Quantrill led the main body of his guerrillas down Massachusetts Street to the Eldridge House. The provost marshal of Kansas, a guest there, surrendered the hotel. Quantrill accepted, then ordered his men to take the city, wheeling his horse as he cried out: “Kill! Kill and you will make no mistake! Lawrence should be thoroughly cleansed, and the only way to cleanse it is to kill! Kill!”

The massacre was on. The brutality, carnage and devastation can hardly be imagined. Nearly 200 men—representing around 20 percent of the male population of Lawrence—were killed during the attack, many murdered in front of their families. Dozens of homes and businesses were burned to the ground. By the time it was over, the city had 85 new widows and about 250 fatherless children.

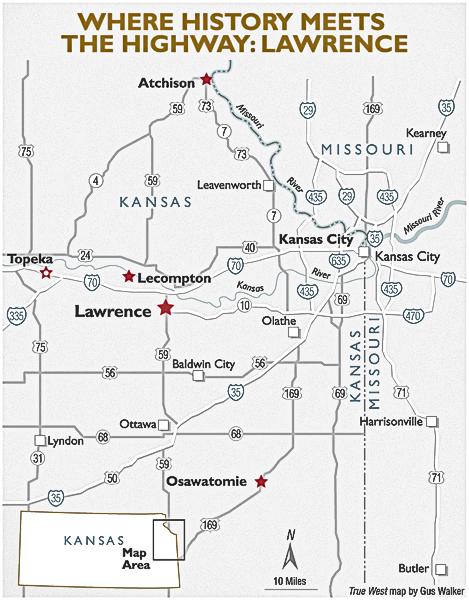

Lawrence had been founded nearly a decade earlier by settlers from the New England Emigrant Aid Company, determined to see the territory enter the Union as a Free State. From its inception, the town was a hotbed of abolitionist sentiment. But clashes occurred all along the Kansas-Missouri border area. In 1856, John Brown led an attack on Missouri raiders at the Battle of Black Jack. As this was the first armed conflict between abolitionist and pro-slavery forces, some historians maintain that this was the real beginning of the Civil War.

The assault on Lawrence didn’t end the way the Quantrill’s Raiders expected. “Rather than scaring people into heading back East, the raid actually strengthened the resolve of the people living here,” says Julie McPike, managing director of Freedom’s Frontier National Heritage Area, which oversees historical sites in 41 counties along the Kansas-Missouri border.

“The town was founded by hardy abolitionist settlers, and they didn’t take the Quantrill Raid sitting down,” notes Keith Manies, assistant manager of the Lawrence Visitor Information Center. “If anything, it made them more determined to rebuild.”

And rebuild they did, aided by the arrival of the rail lines in 1864 and 1867. Lawrence’s population, which had been 1,645 in 1860, soared to 8,320 by 1870.

Today’s Visitor Information Center, located in Lawrence’s restored Union Pacific depot, holds a slew of exhibits on the Border War. The center also offers several tours, one along the route of Quantrill’s Raid, others on segments of the Oregon and Santa Fe Trails.

Much of the town’s post-raid, 19th-century architecture has been preserved in the Old West Lawrence Historic District. The Plymouth Congregational Church, which stands nearby, has been described as a “vision of spires, buttresses and stained glass.”

Even now the city’s seal shows a Phoenix rising from the ashes. “People here were very proud of that heritage back then, and still are today,” Manies says. “The Raid has been a rallying point for the town for 150 years.”

John Stanley, the Arizona Wildlife Federation’s 2007 Conservation Media Champion, is a former travel reporter and photographer for The Arizona Republic.

Photo Gallery

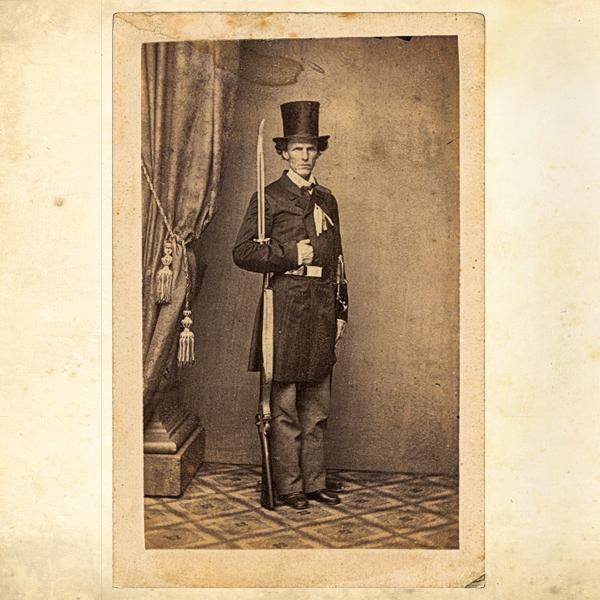

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

– Courtesy Library of Congress –