A banner whips in the wind over the main drag as I drive into Taos, New Mexico, and I figure that Kit Carson is getting his due. I should have known better.

Kit Carson? Who’s that? This is Taos, which has always played by its own rules.

In 2009, Taos was celebrating the 40th anniversary of Easy Rider with the “Taos Summer of Love.” Now I’ve been called a hippie; I can rock out to Steppenwolf, and I give Dennis Hopper a lot of credit for creating one of the most influential movies of the 1960s (it was shot partially in Taos). But Taos wouldn’t have had any hippie communes if not for Kit Carson, and this is his 200th birthday.

Born on December 24, 1809, in Madison County, Kentucky, Christopher Houston “Kit” Carson grew up on a farm near Boone’s Lick, Missouri. As a mountain man, explorer, guide, trapper, soldier, hunter, Indian agent and rancher, he left his mark across the West. Yet he has also been criticized, maligned, debunked and downright despised—I’m a little conflicted about him myself—so you can’t blame Taos for saluting peace, love and art in what became Carson’s hometown.

Over at the Kit Carson Home & Museum, interpreter Teresita Mascarenas hears criticism about Carson practically every day. For years, a Tewa Indian woman named Clara has blasted Mascarenas with verbal assaults such as, “You work for that criminal, Kit Carson!” And she is one of Mascarenas’s best friends.

Kit’s Legacy

Apprenticed to a saddlemaker after his father’s accidental death, Carson ran away from Missouri in 1826 and joined a wagon train bound for Santa Fe, New Mexico. He settled in Taos, although he was seldom home, making his name as a trapper, hunter and guide, marrying two Indian women (one died, one divorced him) before marrying Josefa Jaramillo of Taos in 1843. He was 34. She was 14. Their three-room home (now five rooms) was probably built in 1825 and was a wedding gift from Carson’s in-laws. They hated him, but Josefa loved him.

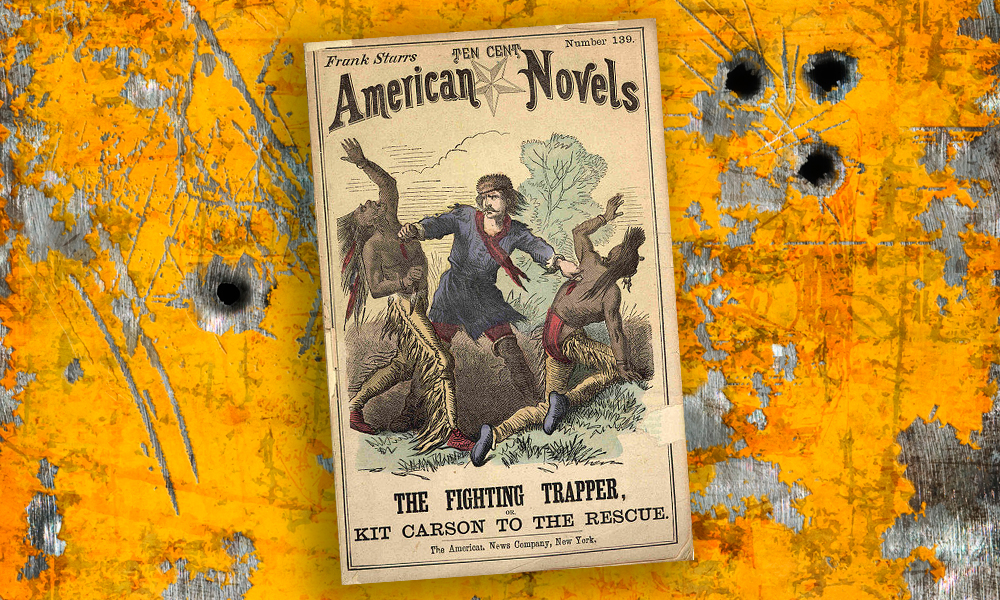

Carson earned a national reputation after he hooked up with John C. Frémont in a steamboat on the Missouri River. Carson guided Frémont’s group to South Pass, Wyoming, in 1842, and led another exploration in 1843-44 that covered much of Utah, Oregon and California. Buffalo Bill Cody named his son after Carson. “His reputation is not tainted with the moral stains that cloud the names of so many Western men who marched in the van of civilization,” Cody wrote of his hero.

He’d get a lot of argument today.

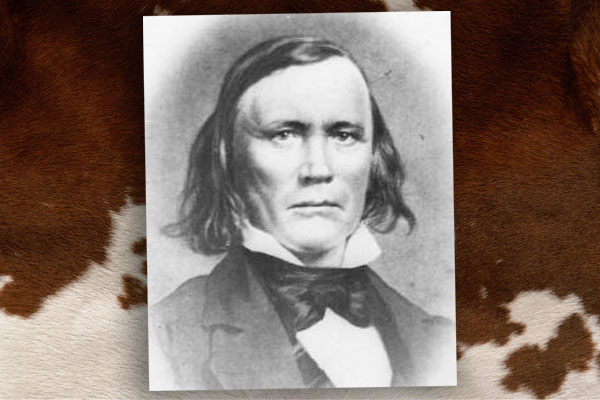

For a hero—even for a contemptible villain—Carson wasn’t much to look at.

“I was very anxious to see a man who had achieved such feats of daring among the wild animals of the Rocky Mountains, and still wilder Indians of the Plains…,” recalled William T. Sherman in his memoirs. “I cannot express my surprise at beholding a small, stoop-shouldered man, with reddish hair, freckled face, soft blue eyes, and nothing to indicate extraordinary courage or daring. He spoke but little, and answered questions in monosyllables.”

Daring he was, but my pocketbook is not as adventurous. You could go broke trying to cover every place Kit Carson touched, so I’m sticking to his Southwestern turf, such as Fort Garland, Colorado.

Established in 1858, Fort Garland was Carson’s home when he commanded the post in 1866, negotiating a peace treaty with the Ute Indians during his year there. In 1950, the Colorado Historical Society took over the adobe fort, restoring a number of buildings, including the commandant’s quarters, which re-create Carson’s era.

Fort Garland reveals Carson in full glory, but to see another side to this man, you will have to head west into the Navajo Country. Then you might understand why Carson isn’t as adored as Easy Rider.

The Other Side of the Story

Canyon de Chelly National Monument is a breathtakingly beautiful treasure of sandstone. Carson, under Gen. James H. Carleton’s orders, led a force into the Canyon in January 1864 to end the Army’s war against the Navajo. In this “scorched earth” war, Carson was relentless. Fires destroyed sheep herds and crops, including the Navajo’s pride and joy—ancient, wonderful peach orchards. Burned.

Okay. War is hell. Carson was following orders. But I hail from South Carolina, which produces more peaches (and better tasting) than Georgia. Peaches are my favorite food. Orders or not, in my book, any man who destroys peach trees by the thousands earns eternal damnation to hell.

At Canyon de Chelly and over at Window Rock (home of the Navajo Nation Museum), you’ll get a different perspective on Carson. The Army marched Navajo prisoners to Bosque Redondo near Fort Sumner. Carson had gone home by then, but many Navajo and some historians hold him responsible for the “Long Walk.”

Some 8,000 Navajos, famished and ill-clothed, began the 300-mile march to Bosque Redondo. The Army divided the prisoners into six groups and drove them east at various intervals, taking different routes. Hundreds died on the march. Many captives were sold into slavery.

The Navajo ordeal is probably the biggest reason Taos—and much of the West—remains hush-hush about Carson, and why Carson gets the short shrift at the new New Mexico History Museum in Santa Fe. I guess it’s not politically correct these days to call Carson a hero and a patriot. The lover of our country during the Civil War who resigned as Indian agent and took a commission as colonel of the New Mexico Volunteers at Fort Union. The guy who raised the American flag on the Taos plaza (Old Glory still flies there 24/7).

Scores of Navajo died at Bosque Redondo before the 1868 treaty sent them back to their homeland. At least one report has Carson pleading for their return: “I’m not sure the Great Spirit means for us to take over Indian lands. Let me lead them back while they still have the will to live.”

I admire that, but then I see burned peach orchards.

As a reservation, Fort Sumner’s Bosque Redondo was a terrible failure. As a memorial, it’s a success. The small museum, designed by Navajo architect David Sloan, provides a fine history about the Navajo ordeal, and we can hope the museum gets even better when the second phase of construction is completed.

A Lot of Adobe Walls

A more heroic look at Carson can be found in the Texas Panhandle. If you can find Adobe Walls, that is. It’s tucked away in the Canadian River escarpment in Hutchinson County between Stinnett and Spearman. (Best bet: Check in at the nifty Hutchinson County Museum in Borger for directions.)

In 1864, Carson had orders to attack Comanche and other Plains Indians. On November 26, he led a force of 400 soldiers and Ute and Jicarilla Apache scouts against a large Indian village. It was almost Carson’s last fight. Estimates of the village size range from 3,000 to 7,000, yet somehow Carson managed to hold off the Indians. Still, in terms of historical significance, it wasn’t much of a battle. Carson’s force suffered about 30 casualties. Indian casualties were estimated at 100 to 150.

More significant is Bent’s Old Fort near La Junta, Colorado. Established in 1833 as a trading post, the fort lasted only 16 years. Now restored to its adobe glory, full of re-enactors/interpreters, the national historic site brings the Santa Fe Trail to life.

Carson arrived here in the early 1840s, hired by William Bent as a hunter. Later, Carson returned to the area, leaving his mark at Fort Lyon and—my personal favorite spot on this trail—Boggsville.

What a name! Thomas O. Boggs founded Boggsville on the Purgatoire River in 1862, and Carson moved here to take up ranching after leaving the Army. Open in the spring and summer, Boggsville Historic Site strives to re-create the days of Boggs and Carson through restored buildings and events such as Boggsville Days, Old Santa Fe Trail Day and a Boggsville Christmas, none to which, by some crazy oversight, I’ve ever been invited.

End of the Trail

Carson was in failing health by the time he moved here. Josefa joined him, but she died of complications from childbirth on April 27, 1868. Carson “just seemed to pine away….” Deathly sick, he went to Fort Lyon. On the afternoon of May 23, Carson began coughing while in the post surgeon’s quarters. Blood flowed from his mouth. “Doctor, compadre, adios,” he called, and he died of a ruptured aneurysm.

He was buried beside his wife.

The following year, Josefa’s family requested that their remains be returned to Taos. Back to Taos I go, to conclude the loop by visiting his grave site at the Kit Carson Cemetery.

Of course, Carson stamped his name across the Southwest: Carson National Forest in New Mexico. The Kit Carson County Carousel in Burlington, Colorado. A town called Kit Carson in Cheyenne County, Colorado. Kit Carson Park in Escondido, California. Kit Carson Middle School in Sacramento. Roads named after Kit Carson in many places, including some towns in the Navajo Nation.

Yet today, even after Hampton Sides’s extraordinary book Blood and Thunder, with its balanced treatment of Carson, it is risky to say Carson’s name too loudly.

Paul Hutton explained why that is in the 2009 Spur Award-winning documentary on Kit Carson that aired on PBS’s American Experience: “He represented his country, and he represented what America was becoming. And so when we look at Kit Carson if we get uncomfortable, well, that’s cause we’re looking in the mirror, and we’re seeing ourselves.”