Each year Western Writers of America (WWA) adds a distinguished writer to the Western Writers Hall of Fame (HOF).

Each year Western Writers of America (WWA) adds a distinguished writer to the Western Writers Hall of Fame (HOF).

With the breadth and depth of writers who created “Literature of the West for the World” to select from, the decision is based on a vote of the organizational membership.

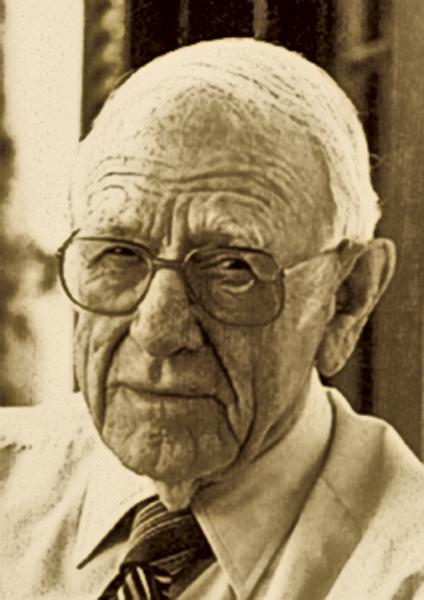

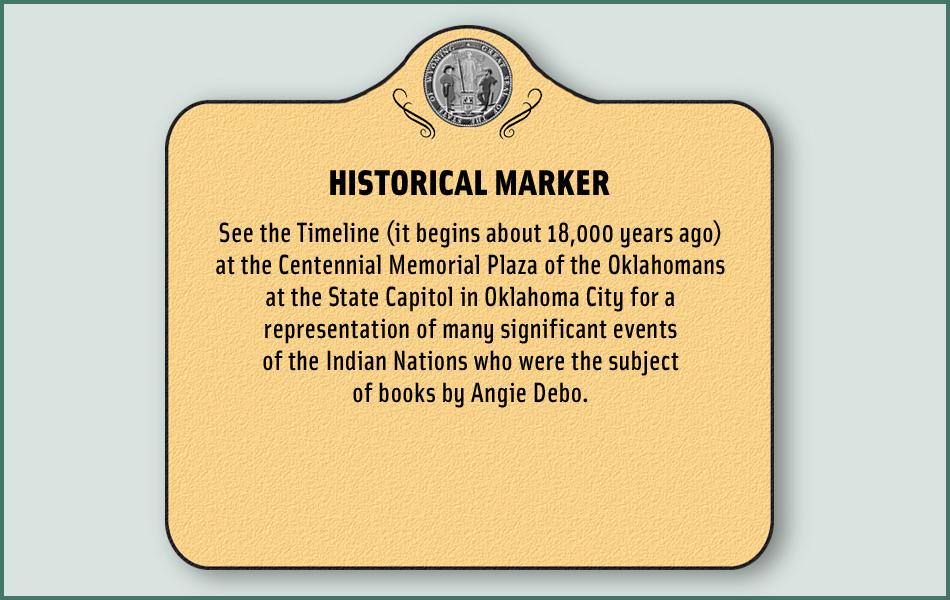

Inducted into the HOF this year is Angie Debo, a writer who broke through boundaries when she departed from the Turner thesis to view the West as a story of conquest rather than settlement. Her first book, The Rise and Fall of the Choctaw Republic set the theme of her writing as she developed major histories of the tribes of Oklahoma including The Road to Disappearance: A History of the Creek Indians. She also wrote Tulsa: From Creek town to Oil Capital; a revisionist biography, Geronimo: The Man, His Time, His Place; and, a summary of all tribes, A History of the Indians of the United States.

Debo is the latest of the important women of Western Literature to be included in the Hall of Fame.

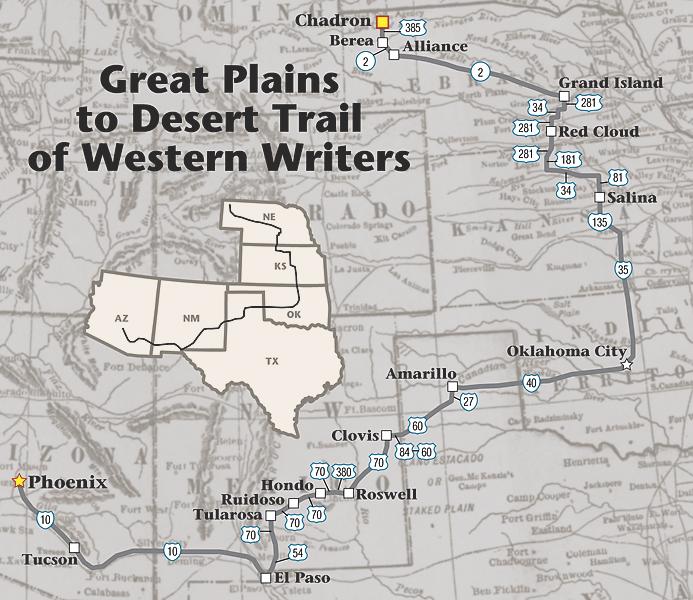

Let’s take a little journey through the writings and the places of some other Hall of Fame members.

Sandoz and Cather write of Nebraska Landscapes

The Sandhills of northwest Nebraska inspired Mari Sandoz, known for her biographies, Crazy Horse and Old Jules, a story of her father, plus other books drawn from the landscape: The Buffalo Hunters, The Cattlemen and The Beaver Men. Of all her books, the one that is my personal favorite is Love Song to the Plains, a homage to the landscape that shaped her and influenced everything she ever recorded with pen or typewriter.

The Mari Sandoz High Plains Heritage Center at Chadron State College includes details about Sandoz and her work in the Carmen and John Gottschalk Mari Sandoz Exhibition Gallery. Sandoz won a Spur Award from WWA for her juvenile book, The Storycatcher and received the Saddleman Award (now called the Owen Wister Award) given for lifetime achievement from WWA in 1964. She was also inducted into the Hall of Great Westerners at the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.

Also making a name for herself by writing the stories of Nebraska’s pioneers is Willa Cather who spent her early youth in Red Cloud, Nebraska. Although she made her home in the prairie town only six years during her childhood, Cather called upon her experiences there, and most of all upon the people she knew there, for scenes and characterizations in the novels that won her critical acclaim. The community is the Sweet Water of A Lost Lady, the Frankfort of One of Ours, the Haverford of Lucy Gayheart, the Black Hawk of My Antonia and the Hanover of O Pioneers!

Among the individuals she knew who cropped up in her work, the best known character is Antonia, drawn from the real-life Annie Pavelka, while the Harling Family in My Antonia is based upon the family of her best friend, Carrie Miner. Similarly Cather used real places for her scenes and settings. The Garber Grove and Garber house in Red Cloud sit within a thick growth of cottonwood, which marks the original site of the Red Cloud Stockade, the Silas Garber House and his earlier dugout. Cather wrote A Lost Lady about Lyra Garber, wife of Silas, the man who once served as Nebraska’s governor. The homestead of Cather’s uncle, George Cather, southwest of Bladen, became the setting for her Pulitzer Prize winning novel One of Ours. Of course the Pavelka farmstead, also located near Bladen, became a setting for My Antonia.

The Pavelka homestead is part of a Bohemian settlement in Webster County, and is now included on the National Register of Historic Places, due to its Bohemian influence and also because of Cather’s writings. The Republican River itself became a predominant setting—almost a character—in several of Cather’s works.

Located just south of Red Cloud is the Willa Cather Memorial Prairie, a 600-acre area now owned by the Nature Conservancy. The prairie characterizes the land Cather and her family found when they arrived in Nebraska, and it had a profound, and lasting influence on Cather. She once wrote: “This country was mostly wild pasture and as naked as the back of your hand. I was little and homesick and lonely and my mother was homesick and nobody paid any attention to us. So the country and I had it out together and by the end of the first autumn, that shaggy grass country had gripped me with a passion I have never been able to shake. It has been the happiness and the curse of my life.”

The people of Red Cloud and Webster County call the area Catherland. They promote it with an annual festival the first weekend in May devoted to Willa Cather’s work. The Nebraska State Historical Society has preserved Cather’s childhood home.

This route takes us through Oklahoma, the home of the people most central to Angie Debo’s books. She is remembered for And Still the Waters Run, a controversial assessment of how Indian lands in Oklahoma were taken from the tribes. Debo also wrote two books that fall in the fictional realm, albeit with a large measure of history thrown in: Prairie City: The Story of an American Community and Tulsa: From Creek Town to Oil Capital.

Southwest History, Novels and Screenplays

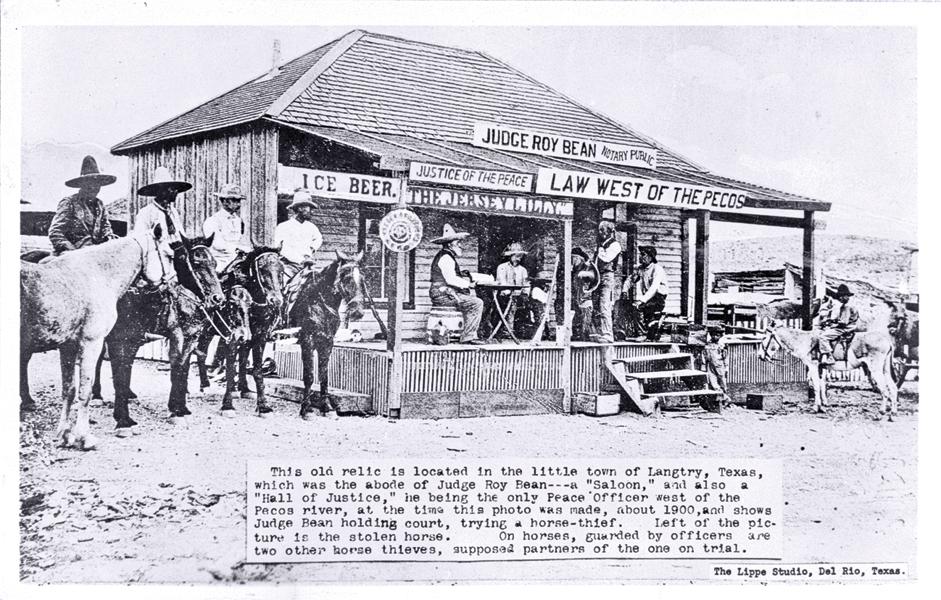

From Angie Debo’s Oklahoma, I continue south to Texas where Charles Leland Sonnichsen, known to friends and colleagues as Doc Sonnichsen, worked and wrote. This English professor at the University of Texas El Paso also chaired the English Department, served as dean of the graduate school and became a renowned researcher and writer. Among his 27 books are Roy Bean: Law West of the Pecos; Cowboys and Cattle Kings; The Mescalero Apaches, Tularosa: Last of the Frontier West; Pass of the North: Four Centuries on the Rio Grande (two volumes); Colonel Greene and the Copper Skyrocket; From Hopalong to Hud: Thoughts on Western Fiction; and, his books on Texas feuds, I’ll Die Before I’ll Run, Ten Texas Feuds and Outlaw: Bill Mitchell, Alias Baldy Russell.

Doc Sonnichsen, too, has Spur and Saddleman Awards from WWA, along with a slew of other recognition.

Eve Ball devoted her life and her writing to the Apaches she came to know while living around Ruidoso, New Mexico. Among her best-known books are In the Days of Victorio and Indeh: An Apache Odyssey, co-authored by Lincoln County residents Nora Henn and Lynda A. Sánchez. Her use of Indian oral history for both histories was ground-breaking.

Ball earned college degrees in Kansas, and taught there, but during WWII she relocated to Hobbs, New Mexico, and later to Ruidoso, where she bought property near Ruidoso Downs, the famous horse-racing track. This was on a route Apaches took when they walked to town from the Mescalero Apache Reservation. The Apaches would stop and visit with Ball, who provided them with cold water, or sometimes a glass of lemonade.

In their first “visits” she would ask questions and get “yes” and “no” answers. But in time she realized “that the fewer questions I asked, the more they would tell me,” she once said. The visits became interviews with such individuals as James Kaywaykla, nephew of Warm Springs Chief Victorio and grandson of Nana, and Ace Daklugie, a nephew of Geronimo.

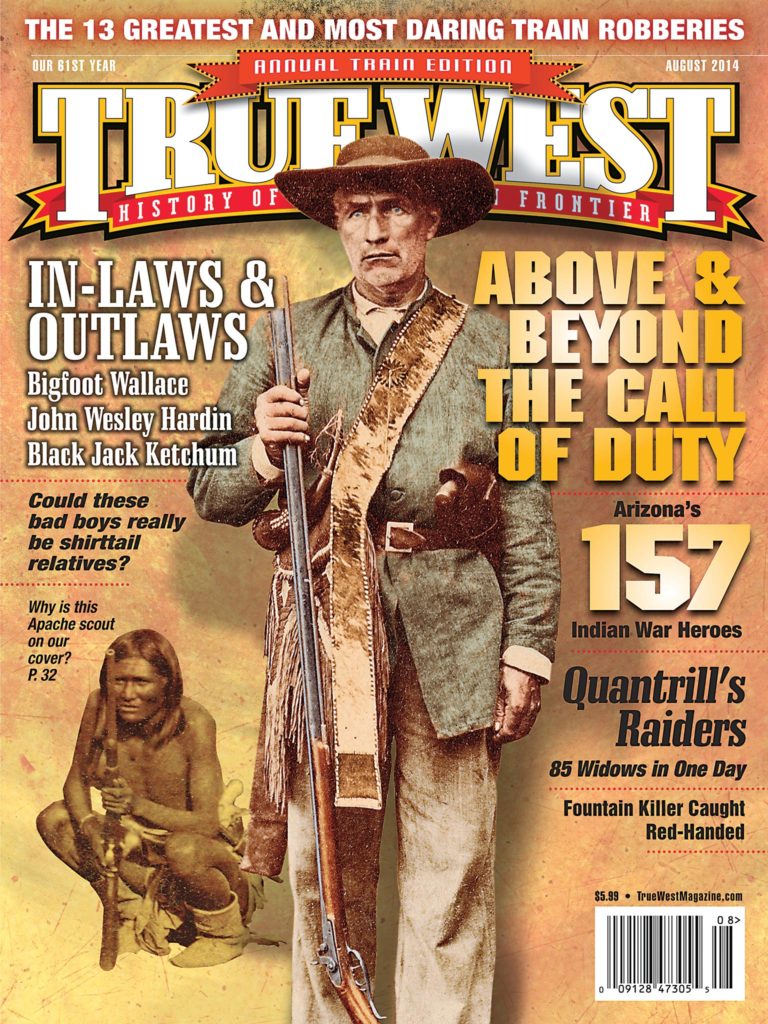

She also wrote articles for Western magazines, including True West and Frontier Times. Her short subject article, “Buried Money” published by True West won her a Spur Award from WWA for 1974.

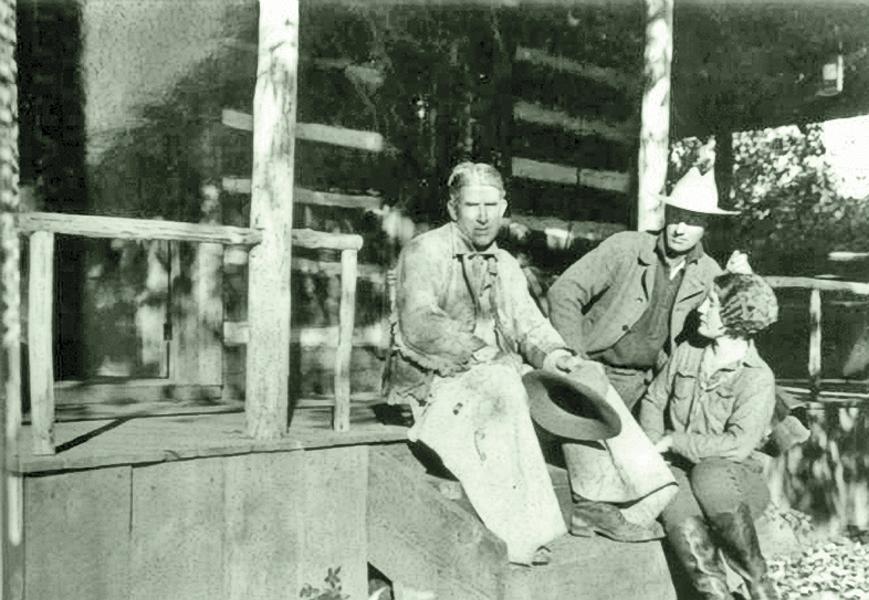

Zane Grey wrote books strongly rooted in the traditional West. This man who studied dentistry in Pennsylvania, first saw Arizona on a mountain lion hunting trip. The landscape captured him, and he began writing of the Southwest. Grey’s Riders of the Purple Sage, published in 1912, propelled him to Western writer stardom. He churned out books, writing in a cabin on the Mogollon Rim in Arizona, bringing to readers around the world stories of the Southwest and Manifest Destiny. In 1990, the Dude Fire burned the Zane Grey Cabin, which had been restored and had become a popular tourist destination. In 2003, a replica of the Zane Grey Cabin was rebuilt in Payson on the grounds of the Rim Country Museum. Also, the Zane Grey Museum in Lackawaxen, Pennsylvania, is far from the landscape where he set so many of his books, but it holds collections related to his Western writing career.

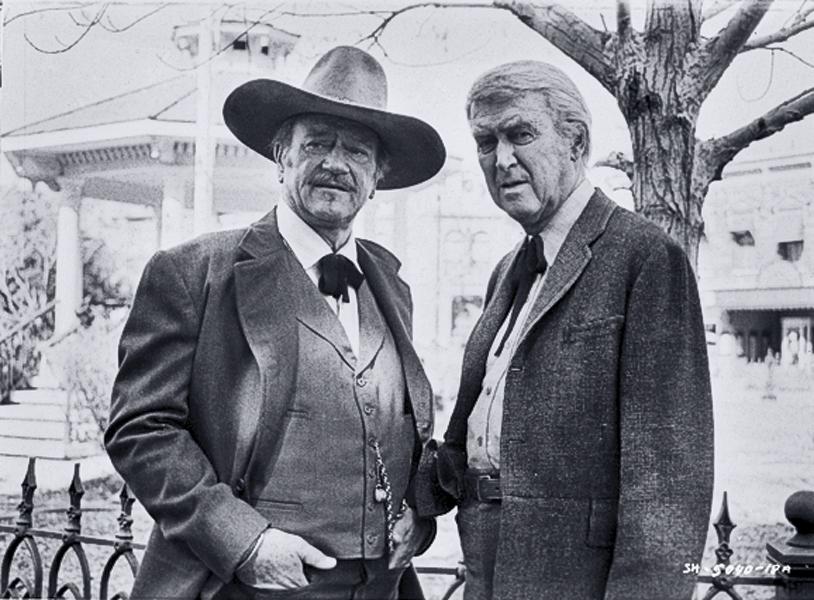

Glendon Swarthout came from Michigan to Arizona and created characters larger than life, developing storylines that would transcend generations. One of his best-known stories, The Shootist, was adapted for film by his son Miles Swarthout, and became the final, powerful film role for John Wayne. Swarthout turned to the Nebraska plains for another of his signature character studies, The Homesman, a tough story about Nebraska homesteader women who, unable to deal with the isolation, hard work and sometimes unbearable loss they face in their lives, are sent back east with a man whose job it is to take them to a home where they can be more secure. This novel is now on the big screen in a film released this year starring Tommy Lee Jones, Meryl Streep and Hillary Swank.

Other Swarthout books also became films including Seventh Cavalry, They Came to Cordura and Bless the Beasts & Children, all produced by Columbia Pictures, and A Christmas to Remember, which became a CBS movie in 1978. In a departure from the West, his early work as a college professor gave him a unique view of life and led him to write Where the Boys Are, a comic account of the spring break ritual of college students from Michigan State, which became an instant beach story classic when filmed by MGM in 1960.

A common theme for all these writers is how the landscape from the Great Plains to the Southwest shaped their work.

Candy Moulton is the executive director of Western Writers of America.

Photo Gallery

Oklahoma writer Angie Debo is the newest inductee into the Western Writers Hall of Fame.

– Courtesy University of Oklahoma Press –

– Lynda Sanchez –

– Courtesy Miles Swarthout –

– Courtesy Warner Bros –

– Courtesy Western Writers of America –

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

– Courtesy Nebraska Tourism –

Mari Sandoz wrote the lyrical Love Song to the Plains, a literary biography of Crazy Horse, and the story of her father in Old Jules.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

– Courtesy Nebraska Tourism –

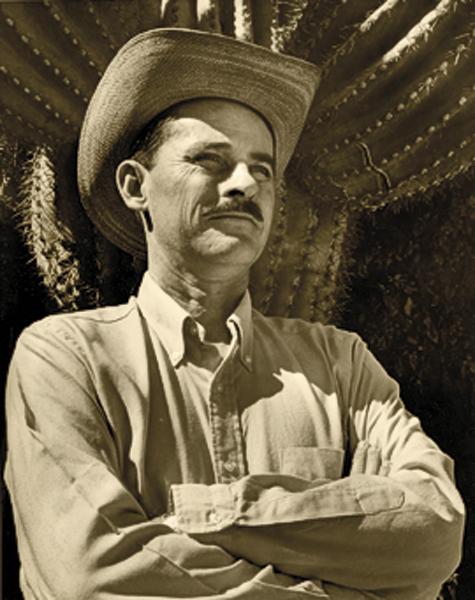

Zane Grey (holding hat) loved spending time at his cabin near Payson, Arizona, and hunting, fishing and riding the wild lands of the Mogollon Rim country, which inspired many of his novels, including To the Last Man, based on the Pleasant Valley War.

– Courtesy True West Archives –