Many men and women came west in the 19th century to pan out that dream of getting rich but none can match that of a pretty Irish lady named Nellie Cashman. A restless adventurer, Nellie ranged the Old West for fifty years prospecting for gold and spreading good cheer wherever she traveled. She made and lost, or gave away, a number of fortunes during her lifetime.

She ran restaurants and boarding houses, never refusing a meal or a room to some hungry, down and out miner who had no money to pay. When a miner was killed in a mining accident there were no benefits for the widow and her children, so Nellie headed straight for the saloons on Allen Street with her hat turned upside down, collecting money. And she always left with a hat full.

Ms. Cashman was always willing to grubstake some prospector on the slim chance that he might strike it rich, in which case she would share in the bonanza. More likely, she would lose her investment, but that never dampened her enthusiasm for “bucking the tiger,” or betting against the odds. She loved to make money and she spent most it on charitable causes. One of her grubstakes did pay off handsomely, netting her $100,000, enough for a secure retirement. But Nellie gave most of it away. Her philanthropy and generosity earned her the respectful title, “Angel of the Mining Camps.”

The Tombstone Epitaph, had this to say about Nellie and a September, 1880 edition: “Nellie Cashman, the irrepressible, started out yesterday to raise funds for the building of a Catholic Church. We don’t know what success attended her first effort, but will bet that there is a Catholic Church in Tombstone before many more days if Nellie has to build it herself.”

Nellie Cashman participated in many worthy causes. Her requests for donations brought her in contact with cowboys, miners, gamblers, and the ladies of the evening. The source of donations never bothered her. She said: “Whether the money comes from an upstanding citizen, or a member of the outlaw faction makes no difference to me,” she said. “The money doesn’t know the difference either. What matters is what it is used for, and I see to it that in one way or another, it helps humanity.”

Nellie was born in Ireland’s County Cork in 1845. Historians disagree as to how she and her family arrived in the United States. One version says her father Patrick died around 1850 so Nellie, her younger sister Frances “Fannie”, and her mother, immigrated to the United States soon after. Around 1865, the three of them traveled by ship to Panama, across the Isthmus by train and on to San Francisco.

Another says her father Thomas came to America around 1858 to find work before sending for his family. Nellie, her mother and sister arrived in Boston in the spring of 1860. Thomas died during the Civil War and in 1869 the two adventure-seeking girls rode on the new transcontinental railroad to San Francisco.

San Francisco in those days was the nation’s tenth largest city and the Irish made up a third of the population. So, unlike Boston it was easy to fit in. There was no anti-Catholic, nor anti-Irish sentiment in the city made up of ethnic groups from all over the world.

Soon, Fannie met, fell in love and married another Irish immigrant Tom Cunningham. He was a successful businessman and being good Irish Catholics they soon had five children.

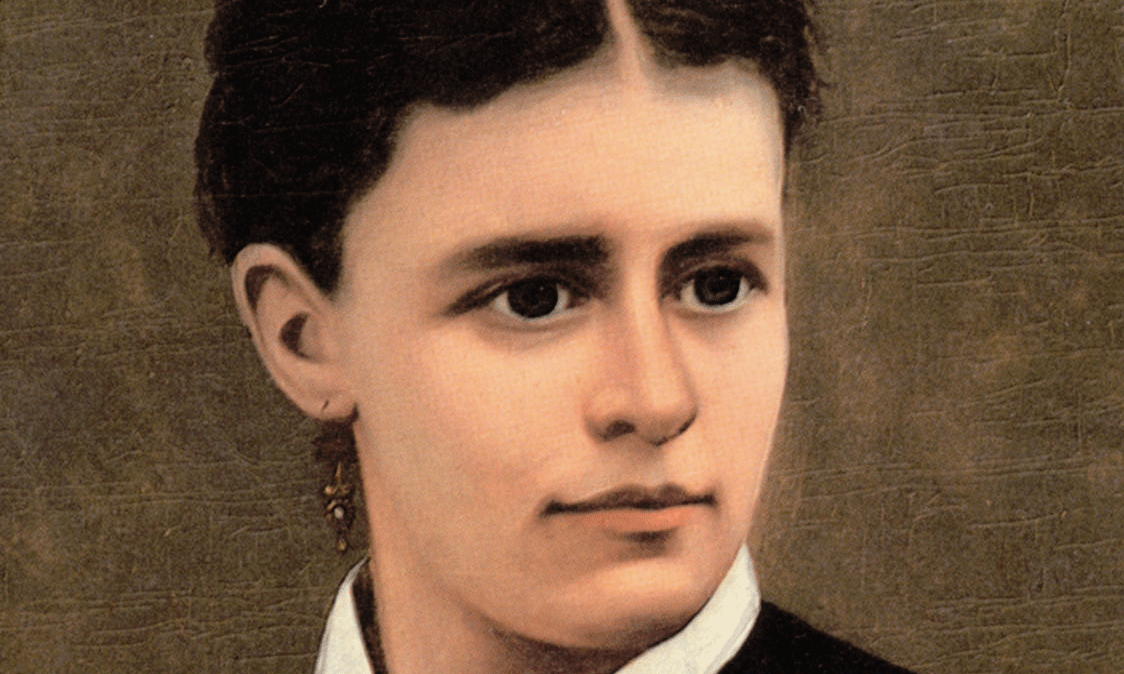

Nellie, a petite lady barely five feet tall, slender figure with dark hair and large, luminous eyes had many offers but preferred to stay single. Married women, even in the West, had too many restraints and Nellie was a lady filled with wanderlust. She did have suitors. One newspaper story had her romantically linked to an Irish mining entrepreneur named Mike Sullivan but nothing ever came of it.

Did being a pretty lady alone in a wilderness with love-starved men ever pose a problem? Not according to Nellie. She’d reply sweetly, “if you act like a lady, men will treat you like one.”

In 1872, she headed for the silver boomtown of Virginia City, Nevada and opened up a restaurant. Two years later she followed the gold rush to British Columbia where she prospected and ran a boarding house for miners. When she heard that a group of miners was ill up in the snowy high country, Nellie hired six men to help her haul 1500 pounds of provisions to the stricken men. She donned snowshoes and pulled a sled, surviving a snow slide along the way.

When Nellie learned of the great silver strike at Tombstone she pulled up stakes and headed for Arizona, arriving in 1800. A few months later, in February, 1881, her brother-in-law, Tom Cunningham, died of tuberculosis in San Francisco. Fanny, suffering from the same disease, packed up their five children and moved to Tombstone where she and Nellie opened a boarding house called the Russ House. Two years later Fannie died, leaving Nellie to raise the children. Her dying request to her sister was to raise her children and give them a good education. Nellie would that promise.

Now a single mom, she was busy raising four kids and running the Russ House in Tombstone during the heyday of the legendary “Town Too Tough to Die.” She quickly became one of the most influential leaders in the rough-hewn community, and was a resident at the time of the notorious “Gunfight at the OK Corral.”

In Tombstone, the Irish made up a big majority of the population, as they did in most of the communities of the West during those years.

Nellie had the “Luck of the Irish,” to go along with a keen knowledge of geology and business. She’d arrive when a boom town was in its early stages, build up a successful business, then sell out and move on before the boom town went bust. During her time in Arizona she operated businesses in Tombstone, Tucson, Nogales, Harqua Hala, Globe, Bisbee and Yuma. She made and gave away several fortunes mostly to the Catholic Church, other good causes and the poor.

Known for her gypsy-like moves, she might have also had businesses in Jerome and Prescott. The years, 1890 to 1895 are missing chapters from her life.

On numerous occasions she organized and led expeditions in the wilderness seeking another fortune. In 1882, she led a party of prospectors heading for Mexico’s Baja California in search of gold. Nellie was one of those rare individuals who became a legend in their own lifetime and it’s sometimes difficult to separate fact from fiction. One such story came out of the trip into Mexico. It was said the party got lost in the desert themselves and Nellie was the only one fit to go for water. She made her way to an old mission where the kindly padre helped fill her canteens with water. Nellie was all that saved twenty prospectors from dying in that searing Mexican desert. The story is told that she found gold near the mission and could have started a rush but the padre told her it was the mission’s only source of wealth and so she kept the secret. Nellie never told that story but her admirers did.

In reality, by the time Nellie and her friends, including future U.S. Senator from Arizona Mark Smith, reached the area, the gold had played out and they went home empty-handed.

On the return voyage home, again, this oft-told story could be an embellishment, Nellie booked passage for her and her friends on a small Mexican boat. On the way the captain got drunk and was unable to control his drinking so Nellie locked him up, took over the boat and landed them safely in Guaymas. In Guaymas, the now-sober skipper pressed charges against Nellie, accusing her of piracy on the high seas. Nellie was able to use her charm on the Mexican authorities and soon the group was back in Tombstone. If that story wasn’t true, it coulda been.

In the late 1880’s Nellie headed for South Africa looking for diamonds and by 1898 she had joined the gold rush to the Klondike. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police wouldn’t all Americans to enter Canada without 2,000 pounds of supplies and equipment so Nellie, now 54 years old, packed up and down the steep, snow-covered inclines of Chilcoot Pass several times until she met the Mounties requirements. While waiting for the spring thaw, she built herself a flatboat and then floated some 500 miles down the Yukon River to Dawson where she prospered by operating restaurants and prospecting for gold.

Nellie spent her last years with her dog sled team combing the vast lands of the frozen north searching for one more gold strike. She became known as the “Champion Woman Musher of the Yukon.” When she was 76 years old, the indestructible Irish lass mushed a dog sled 750 miles from Nolan Creek to Anchorage. Her health was now declining and she died three years later at Victoria, British Columbia on January 5th, 1925. Nellie Cashman was truly a “Woman Who Matched The Mountains.” That wasn’t her epitaph, it shoulda been.