Put me somewhere west of East Street, where there’s nothing left but dust,

Put me somewhere west of East Street, where there’s nothing left but dust,

And the boys are all abustling

and everything’s gone bust;

And where the buildings that

are standing sort of blink and blindly stare

At the damnedest finest ruins ever gazed on anywhere.

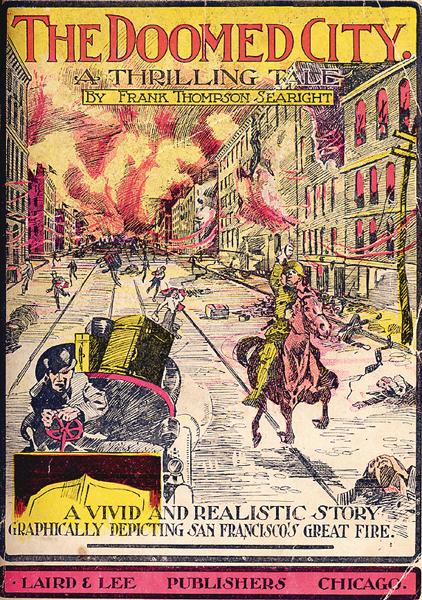

So went the verses by Larry Harris, written soon after a double disaster that all but destroyed one of the West’s social and commercial hubs and, indeed, one of the world’s greatest cities. His lines proved that, regardless of what might happen to San Francisco itself, no force was capable of extinguishing its unique spirit of pride and pugnacity.

Of the twin perils, the earthquake was the first to strike—at 5:12 a.m. on Wednesday, April 18, 1906. The precise time is unascertainable, as the clocks and measuring instruments which felt the disturbance were all at slight variance with each other. Since the Richter Scale had yet to be invented, no precise magnitude for the shock is available; 8.3 is one of the more common estimates, devised from the abundant evidence. By some standards, it was a “moderate” temblor, though there was certainly nothing un-spectacular about its after-effects.

The quake took place on the San Andreas Fault, a long fracture in the earth that has cleaved California in half for millennia. Its epicenter was first thought to be at Tomales Bay, northwest of San Francisco, but more recent evidence suggests it was closer to the immediate southwestern portion of the city. Boats in the water at that time were slapped around like children’s toys in a bathtub; one crew swore its ship hit bottom three times.

The shock was felt around the world. In Tokyo, seismographs tracked it for almost 10 minutes, and in Birmingham, England, the waves continued for a quarter-hour more.

In town, the pavement undulated furiously—as though the ground was sitting atop a heavy surf. Some buildings literally danced on their foundations. Gaping holes and fissures opened all over the streets. The noise was described by one witness as sounding like “thousands of violins at discord.” Most of the chimneys in town collapsed, making the skyline look oddly different in the quake’s immediate aftermath.

The damage was not confined to San Francisco. To the northwest, at the Skinner Ranch in Olema, sitting astride the fault zone, the soil shifted to an amazing degree: a row of cypresses moved 15 feet toward a shed, and a manure pile was lifted up and replaced 16 feet from its original location. Farther north, in Santa Rosa, a pattern of destruction similar to San Francisco’s took hold. After all the major buildings were shaken down, fires began sprouting in the ruins and succeeded in destroying most of the city. To the south, the almost-new campus of Stanford University was badly smashed, as was the Agnews State Insane Asylum near San Jose, where a total of 112 perished.

Because the earthquake had hit at an early morning hour, many fires and stoves had been lit throughout the area. The shock upset many of them, so San Francisco was soon dotted with small conflagrations. Unfortunately, the mains and pipes delivering water to San Francisco were now broken and twisted, so there were no effective ways to fight the blazes—and they began to multiply. In the meantime, citizens—most of them dazed, some of them naked—began to wipe off the dust and pick themselves out of the debris.

Three prominent citizens helped establish order: the sitting San Francisco mayor, Eugene E. Schmitz; Brig. Gen. Frederick Funston, temporarily in charge of the nearby military installations; and former mayor James D. Phelan. By quickly assigning tasks to a multitude of committees, the city continued to function, and among the ruins general unrest and rioting was unknown. Looters—some of them soldiers, looking to make fast money—were found, though the extent of their pillaging is unknown and disputed. Rumors arose that many were shot and their bodies hurriedly buried or even thrown into the bay.

Explosions After the Dust Settled

While the work of the Schmitz-Funston-Phelan trio and the committees was praised widely after the dust settled, one consensus decision made the city suffer irreparably. With little water available, the use of dynamite to fight fires was sanctioned. The resulting explosions lifted cinders and flaming debris high into the air, depositing them all over town, and creating a monstrous (and, obviously, unanticipated) chain effect. Soon, so many fires had broken out that there was no way to tackle them all quickly.

Volunteer bucket brigades and soldiers used any watery substance or liquid-containing vessels available to fight the ever-advancing fires. Wine, siphon bottles, mops and wet towels were all called into service. Amazingly, a number of houses were still saved by resorting to this crude methodology. At a house situated on Russian Hill, resident and Civil War veteran Edward A. Dakin hoisted his best American flag on a mast, dipped it three times in salute and then left. Military personnel in the area quickly agreed that such a patriotic house should be saved at all cost. It was, and it remains there to this day.

A number of people, some famous at the time and some to become famous later, survived the earthquake. A very young Ansel Adams was pitched against a brick wall when an aftershock hit, breaking his nose; it never healed properly. Writer Mary Austin was staying at San Francisco’s Palace Hotel, as was “tenor of the century” Enrico Caruso. While Austin soon left and sought out refuge with friends, the dazed Caruso insisted on eating a full breakfast and touring the ruins. A day later, as he came to his senses, fear struck, and he made a quick exit. He flashed an autographed photograph of President Theodore Roosevelt to signify his importance and secure his place on a boat leaving town.

Philosopher William James, then a visiting professor at Stanford, offered a sober reaction that could have come only from an academic’s mouth: “In my case, sensation and emotion were so strong that little thought, and no reflection or volition, were possible in the short time consumed by the phenomenon.” Less restrained was Jack London, who risked venturing inside the burning city with his wife Charmian: “East, west, north and south, strong winds were blowing on the doomed city. The heated air rising made an enormous suck. Thus did the fire of itself build its own colossal chimney through the atmosphere. Day and night this dead calm continued and yet, near to the flames, the wind was often half a gale, so mighty was the suck.”

As the flames advanced and whole neighborhoods had to be evacuated, tent cities began arising in the city’s major open spaces. The Chinese and some Italians flooded into Portsmouth Square, and Union Square soon became a ramshackle encampment for the homeless, complete with makeshift stores and soup kitchens. While the people clustered together for support, the flames were slowly eradicating most of San Francisco’s best-known features. The mansions of railroad magnates Leland Stanford, Mark Hopkins and Charles Crocker, sitting atop Nob Hill, were destroyed. Everything from the genteel (Old St. Mary’s Church and Temple Emanu-El) to the disreputable (the infamous Barbary Coast district of saloons and brothels) was consumed.

By Friday, the tireless combined efforts of volunteers and military personnel extinguished all the fires; luckily, they had kept the waterfront buildings safe. Had its port and storage facilities been lost, the job of rebuilding San Francisco would have been infinitely more difficult. The fires had burned for a total of 72 hours, wiping out all but a few scattered pockets of the downtown area and much of the territory “south of the Slot”—Market Street, the city’s main thoroughfare. Ironically, as the firefighting crews departed, a cold rain fell and doused the remaining embers.

Arresting Numbers

A total of 4.7 square miles of San Francisco was charred by the fire, with 28,188 buildings destroyed by flames—most of them wooden. The losses were estimated, in 1906 dollars, as being between $350 million and $1 billion. In today’s money, the losses would be well into the billions.

An “official” tally of the dead, released in 1908, reported that 478 had perished in the disaster. Evidence gathered since that time, accounting for the loss of travelers and minority group members who were undercounted at first, suggests that the real fatality total hovers somewhere between 3,000 and 5,000. Of all the disasters to hit the United States during recorded history, this mortality figure is exceeded only by the approximately 8,000 who died in the 1900 hurricane that hit Galveston, Texas.

Some significant buildings survived the quake and fire, and they can still be seen today. Among the most notable are the Fairmont and St. Francis hotels, the old post office and United States Mint, and the Flood and Mills office buildings. The Montgomery Block, a notable commercial building dating back to the Gold Rush days, was saved—only to be knocked down ignominiously, decades later, to create a parking lot. The noticeable Transamerica Pyramid now stands on its site. If the Block is no more, at least its space is occupied by one of the city’s newer major landmarks.

San Francisco was quick to rebound. The city had recovered sufficiently by 1915 to host the extravagant Panama-Pacific International Exposition. Today, it continues as a major center for commerce, culture and population. San Francisco proved that, whatever crises might take it down, it would never be out:

Got to give—why believe me! On my soul, I would rather bore a hole

And live right in those ashes than go to Oakland mole [across the bay];

And if they’d all give me my pick of their buildings fine and slick,

In those damnedest, finest ruins, I would rather be a brick.