The first place to look for Western art has always been St. Petersburg, Florida. Falling to the ground with so many palm fronds and coconuts are the seeds of new trends in the genre.

Not convinced? Neither were we.

But the American West as pop culture has spread across the globe. So when the editors searched for the up-and-comers in Western art, we surprisingly found some of the most interesting examples at an exhibit at the Arts Center in that city along the central coast of the Sunshine State.

The contemporary artists whose works plaster these pages have all taken it upon themselves to locate a genuine West, or maybe just a sense of actuality in representations of that region. Although their art may seem far-fetched compared to works by more traditional artists who are paying homage to masters like Remington and Russell, these artists strive to answer the same questions: What is the West? And how do we best capture it?

Change in Western art might well be traced to the seminal work of Bill Schenck, who began to comment on clichéd Westerns in 1969. Born in the Midwest, Schenck grew to reject the West while attending art school during his youth. Saying he was tired of its lame incarnations in TV and film, Schenck admits he saw little potential for meaningful art. Spaghetti Western director Sergio Leone changed Schenck’s mind. “The Man With No Name” trilogy demonstrated to the young artist that the West could be simultaneously critiqued and refreshed all in one broad stroke. When Schenck moved to New York in 1970, the Pop Art influences of Lichtenstein and Warhol penetrated his own art and helped to formulate his vision.

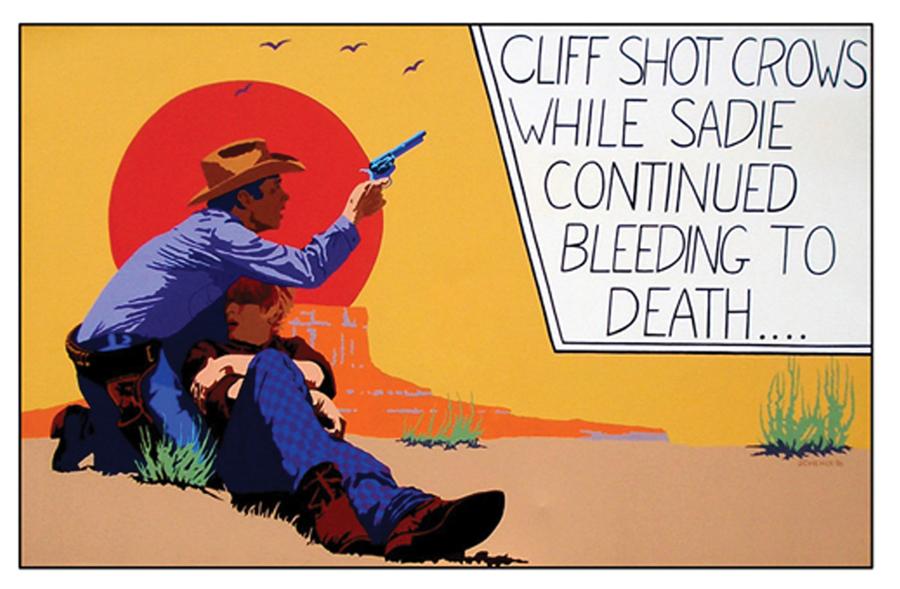

Like Leone, Schenck satirizes the B-Western by toying with our expectations to bring us to a well-constructed punch line. In portrayals of the American West, we are accustomed to seeing the proud figure standing over the injured woman, defending her against an attack or peacefully ushering her from sites of danger.

Schenck humorously and effectively reverses that expectation in Cliff Shot Crows While Sadie Continued Bleeding to Death…. He has painted a typical Western scene, but in neon colors and with the addition of a text bubble that reinforces the absurdity of the scene. The cowboy doesn’t seem to be defending the fallen victim against further attack, but rather he appears distracted from her condition by his own desire to hunt crows. Or perhaps the crows are the source of Sadie’s blood, and the cowboy is defending her, as is the code of the West; yet what good does his defense do her while she lies bleeding to death?

As much as Schenck’s works mock the popular portrayals of the West, and to a lesser extent the West itself, Schenck’s style of Western Pop Realism ultimately brought the artist closer to the region. He now resides in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

A love for the West also drove James Michaels, based in St. Petersburg, to comment on its popular representations. A Pop expressionist, similar to Schenck, Michaels was commissioned by Raymond James Financial to paint a Western image. Like so many other baby boomers, Michaels’ impressions of the West come mostly from film and TV.

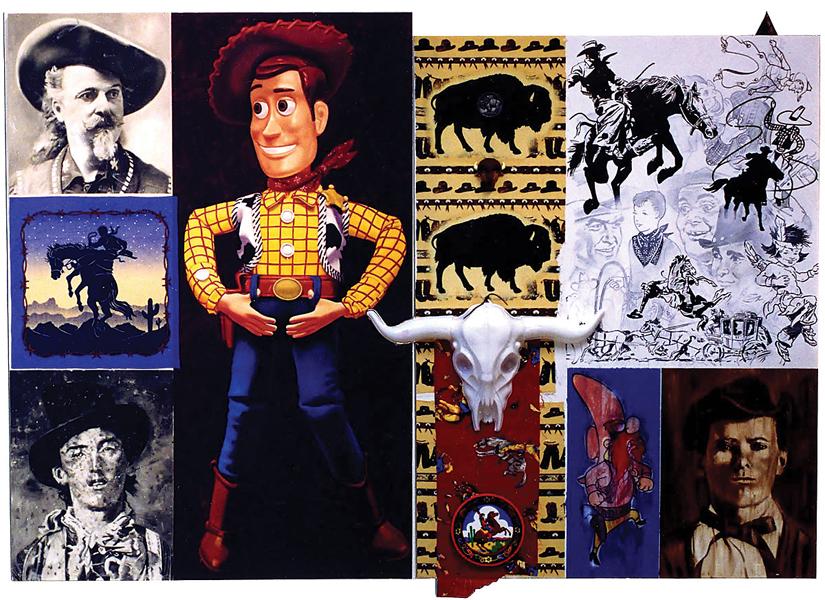

Painting on a large-scale, in part to give his work a sense of the theatrical, Michaels mixes images of his Western heroes without abandon. The result is a stunning juxtaposition of traditional cowboys placed dangerously close to their pop incarnations. His assertion that Woody, the Tom Hanks-voiced cowboy action figure from Pixar’s Toy Story, is not so far removed from Billy the Kid or Buffalo Bill seems natural in Michaels’ The Good, the Bad, the Ugly. At first, the connection between these characters seems forced and ridiculous, but the association of the real and the pretend West makes perfect sense. After all, Michaels is correctly saying that the West of myth, legend and fiction is forever tied to the real West.

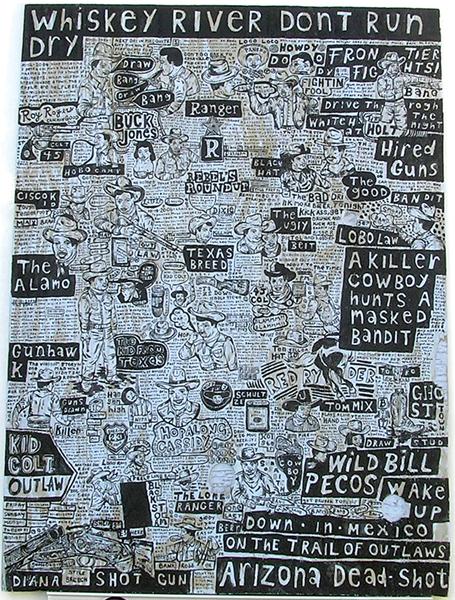

Just as Michaels weaves found images together, Fort Guerin blends found language with images to create a hectic tapestry that tells a Western story. If Michaels and Schenck use their art to come to terms with the West in popular culture, Guerin uses his art to portray his internal efforts to arrive at an understanding of the popular West. In Whiskey River, terms like “The Alamo” and “Hired Guns” come flying from Guerin’s mind in a united stream of consciousness. The words land in a scattered disarray. But in this chaos, there is order. These words and images somehow come together to form a logical and entertaining narrative. You’ll find a story in all of his pieces.

Dependent upon found subject like some of the other artists, Brooklyn artist Jennifer Zackin designed The Divine Fortune? after fate guided her to the small plastic cowboys comprising the piece while she resided in Trivandrum, Kerala, South India. The Divine Fortune takes the shape of a mandala, which is a traditional pattern that can recur in various forms of Hinduism and Buddhism. It most typically represents the universe but can also contain other meanings depending on both the colors used and the orientation of shapes within the elemental circle most mandalas are built upon. The typical mandala, however, is not fashioned out of plastic cowboys.

The search for the material objects was simply part of the art. As The Divine Fortune would have it, Zackin located the set of cowboys that precisely fit her color scheme and conveniently led her to a commentary on consumerism. Three of the Buddhas are popularly represented by these colors:?green aids in the release of jealousy; red, in the release of attachments; and yellow, in freeing oneself from pride or greed. Through this piece of art, she shares the lessons Buddha could teach our country through the iconic cowboy who bespeaks the American dream and the persistence of popular culture.

Or, as Kiowa artist Teri Greeves proves, we can meld popular culture with traditional arts in a fun and practical manner that exposes the beauty of each. Greeves, an extremely skilled bead worker, is best known for work that combines traditional Indian bead working with Pop culture items. The inherent contradiction of infusing Pop into a traditional native art mode gives her work a powerful message to complement its ornate beauty.

She takes modern-day Converse sneakers and embellishes them with beadwork, but not in a way that recalls the beadwork one would have found on moccasins made by her ancestors. Greeves places the word “Kapow!” upon the shoes as if her Indians were superheroes in a 1960’s-era TV show. In a way, this comic-style commentary recalls how Schenck’s work comments on the West, but it also serves another purpose. The unexpected mix is really just an obvious and outwards expression of the art’s overall intent: To mix Indian art with Western Pop culture and come to some sort of understanding between them. The shoes are a microscale representation of a much larger interaction between Native Americana and Pop culture that

is currently taking place in the United States.

Traditional Artists

Pop culture has a tremendous ability to shape thought processes, but no number of Clint Eastwood films can compare with years of work on a ranch. The following artists all bring a sense of realism to their works because much of their art is based on their lives in the West and genuine knowledge of its culture.

Born in California and raised alongside horses, Curt Mattson brings an explosive rawness to his sculptures. The attitude so clear in his work comes from firsthand experience working on ranches based in California to Alberta, Canada. Mattson even learned how to build saddles from his grandfather who encouraged him to pursue a career in sculpture.

His ranching experience translates into a profound realism in Bawlin’ Broncs and Clatterin’ Horns. The sculpture is partly inspired by photos Mattson saw of a cattle drive in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. Well versed in cattle behavior, Mattson recognized the effect that water would have on cattle as they pushed through the dry areas near Jackson Hole. His sculpture is an attempt to capture the bull’s violent need to get to the water. Not so much a comment on bovine behavior, the piece is a still moment taken from a long cattle drive. Far from Pop culture, the sculpture is the translation of a visceral experience.

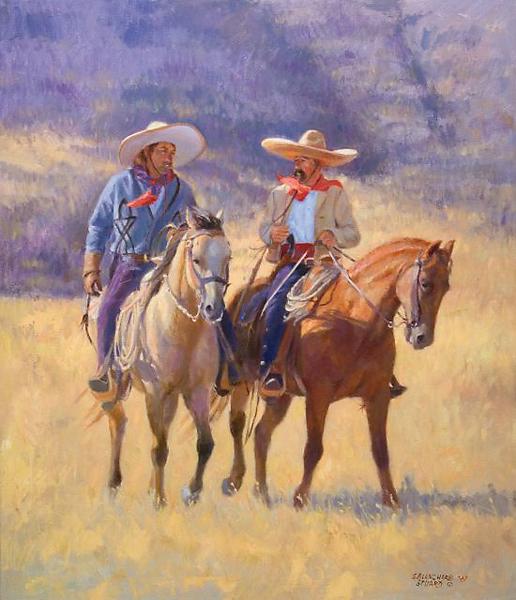

As intimate as Mattson is with horses and cattle, Scott Myers actually attended veterinary school. His background as a veterinarian is evident in his work, Cowhuntin’ as the horses that occupy its center possess a unique anatomic reality. As a consequence, they seem lively and real in a way beyond even the work of the early Western artists. Selectively researched and applied realism still has the potential to modernize a genre.

Larry Fanning brings animals to the center of his art as well. Although his wildlife art is part of a different genre, his practice in painting wolves, elk, moose and deer seems to pay dividends when he transitions to cowboys and historical scenes. His human subjects bring an animal ferocity to their postures and attitudes. Through a non-traditional method, Fanning brings the time-honored practice of portraying the independent cowboy as powerful and partially wild to life.

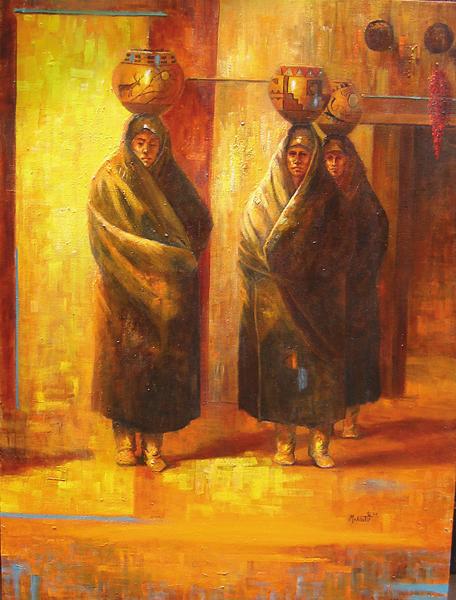

Pat McAllister asserts different sorts of tradition in her paintings. Partially informed by her heritage as a member of the Echota Cherokee Tribe of Alabama, McAllister often portrays Indians in her art with the help of friends and family as reference models. She also brings a European sensibility that she gained while studying there for 11 years. The Dutch Renaissance influences evident in her art are something of a departure from standard Indian art. For instance, her Water Bearers features elements of chiaroscuro, a strong differentiation between light and dark. The seamless transition between European art and Indian art influence lends an honest strength to McAllister’s work.

With Vaqueros, Sherry Blanchard Stuart recalls Frederic Sackrider Remington’s work directly. Stuart employs a color scheme similar to that used by Remington more than 100 years ago. Forward motion often comes from an understanding of the past. By reconstructing a historic subject, in this case cowboys, through a historic influence, Stuart actively preserves the medium. Like the contemporary artists, Stuart uses her work as a means of expressing commentary. For her, the message, as an accomplished artist herself (her work has been featured at the prestigious “Cowgirl Up!” show in Wickenburg, Arizona), is that Remington’s work is still valid.

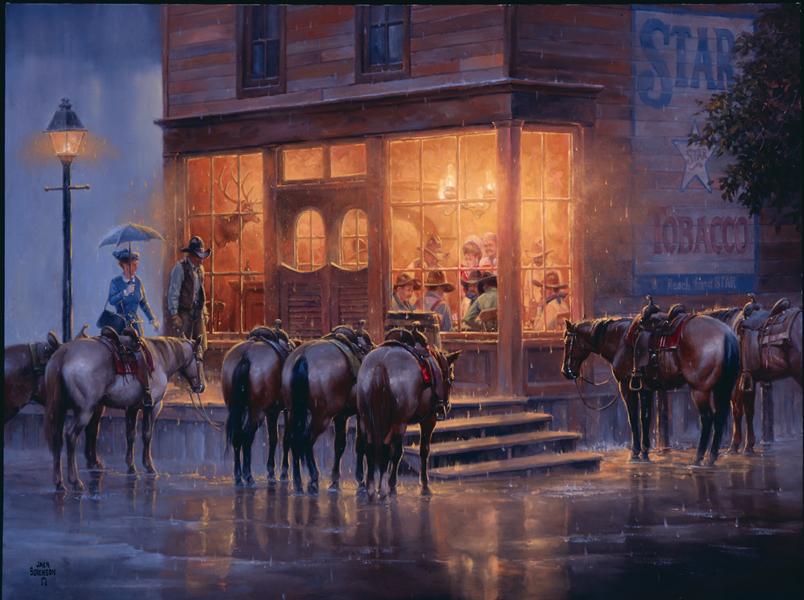

Jack Sorenson creates art to preserve the past as well. Raised in Amarillo, Texas, Sorenson actually drove a stagecoach for a living. He says his kids believe he was raised in the Old West thanks to the photographs that capture him behind the reins. Through his art, he recreates a frontier era that will never come again. Sorenson has the unique personal history of living in both the fantastic West and the genuine West.

What is Western Art?

To keep Western art fresh, the form and content of the message delivered in the medium must be masked by an artist’s experiences. For Zackin, she chose to evaluate Pop Western influence on Indians by placing small figurines in an elaborate pattern. Michaels examined his nostalgia of the West by placing his childhood Western influences side-by-side. And Myers’ work as a veterinarian brings a unique sensibility to animals not seen in most art in the genre.

Western art, for all these individuals, is really part of a search. They use the genre to locate themselves as well as the region. Art becomes a compass which points due West.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Curt Mattson –

– Courtesy Fort Guerin –

– Courtesy Raymond James Financial –

– Courtesy Larry Fanning –

– Courtesy Sherry Blanchard Stuart –

– Courtesy Pat McAllister –

– Courtesy Bill Schenck –

– Courtesy Jack Sorenson –

– Courtesy New Mexico’s Museum of Fine Arts –

– Courtesy Jennifer Zackin –