In the mid-18th century, when Spain’s King Charles III learned that Russian explorers and fur traders were settling along the Alaskan coast, he decided it was time to claim Alta California and establish colonial control.

In the mid-18th century, when Spain’s King Charles III learned that Russian explorers and fur traders were settling along the Alaskan coast, he decided it was time to claim Alta California and establish colonial control.

Successful colonization required three dwellings: Missions, so priests could convert Indians to Catholicism and teach them how to become self-sufficient; Presidios, for the military and Spanish administrators; and Pueblos, for civilian settlements.

Father Junipero Serra was chosen to coordinate the mission project, and between 1769 and 1823, he and his Franciscan followers built a chain of 21 missions that were a day’s travel apart by horseback. These missions stretch from San Diego in southern California to Sonoma in northern California.

California’s El Camino Real has its roots in 16th-century Spain with the building of new roads that led to the King’s residence. These roads became known as Royal Roads or Caminos Reales. What began as a rough footpath in San Diego (now Presidio Park) continued north 650 miles, carrying the culture and language of Spanish Mexico through Alta California and linking the missions. The original El Camino Real is no longer one road but a tangle of interstates, freeways, city streets and county roads. For this trip, I’ll visit the missions in the order they are found on the map, not according to when they were founded.

Northward Ho!

I begin my trek where Father Serra began. Well, sort of. I mistake San Diego’s Serra Museum (built in 1928) for the mission and am informed it’s a common error. But after receiving proper directions, I drive onto Highway 8, heading north.

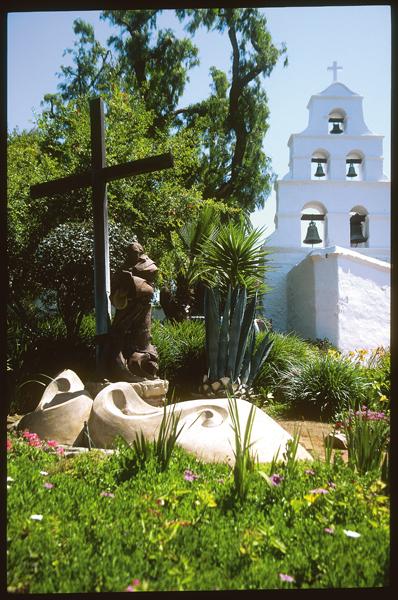

Mission Basilica San Diego de Alcala (the Mother of the Missions) was the first mission to be dedicated. On July 16, 1769, Father Serra swung a bell in a tree, raised a great wooden cross and preached a sermon. This simple ceremony was repeated at the founding of every succeeding mission. Here, I find an excavation in progress of a soldiers’ barracks and an archaeologist on duty who is happy to talk about it.

Venturing onto Interstate 5, I make a quick stop at Mission San Luis Rey de Francia, called the King of the Missions. It’s also home to a sub-mission: San Antonio de Pala, which was built for the Indians in the area. Today, it is the only mission-related structure still ministering to Indians.

I then head to Mission San Juan Capistrano, the Jewel of the Missions. Spring is definitely the time to visit this mission, if not all of them, because of the Capistrano’s spectacular gardens. For all its grandeur, this mission has gone to the birds—the swallows, that is. Every year, on March 19 (St. Joseph’s Day), the swallows return to Capistrano, build their clay nests under the tile eaves and raise their young. After spending hours at the mission, I head across the street to a patio restaurant and indulge myself—in everything.

Entering the Los Angeles Area

Not far off Interstate 5, I find Mission San Gabriel Arcangel, the corner stone for the city of Los Angeles. A little farther north is the Mission San Fernando Rey de Espana. In spite of the traffic, the congestion, the smog and the over-crowded freeways, they both are worth a visit.

Following the California Coastline

Only when I leave Interstate 5 for the 101 North do I begin to see why people love California. On Highway 126, on my way to Ventura, home to the Mission by the Sea, I pass Fillmore, home of the Fillmore & Western Railway (you may recognize it from Seabiscuit). Unfortunately, I don’t have time to check out the railroad’s collection of movie trains, but it makes a nice side trip.

San Buenaventura, my mission for this trip, is small and charming. When the Fathers discovered this place, they also found a large population of friendly Chumash Indians who were skilled in fishing, canoe building and weaving baskets so tight they could hold water.

Farther up the coast, Santa Barbara, the Queen of the Missions, stands in an amphitheater formed by the Santa Ynez Mountains and the curving coastline. The Lone Woman of San Nicolas Island is buried somewhere in the mission cemetery. She was immortalized as the character of Karana in the children’s novel Island of the Blue Dolphins.

A few miles after 101 turns sharply north, I make a right on 246, pass the Danish village of Solvang (not without stopping, of course) and come to Mission Santa Ines, where I hear the angels singing—or, rather, a choir that sings like I suppose angels would.

Heading the opposite direction on 246, toward Lompoc, is Mission La Purisima Concepcion de Maria Santisima, which is on a 2,000-acre California State Historical Park. The mission’s living history museum features Chumash homes built of tule reed, tallow vats and pens full of oxen and other animals raised for work and food. This is the U.S.’s only fully restored example of Spanish Colonial Mission architecture. The gardens show typical mission-era plants used for food, fiber, medicine and perfume. Signs identify each plant and its use, for example: “Hollyleaf Cherry: The cherry pits were crushed to prepare gruel known as atole.”

On the 101 again to San Luis Obispo de Tolosa and another embarrassment. I can’t find the mission. Between the traffic, the one-way streets and no visible signs, I don’t have a trail to blaze! (Although I never reach the mission, that’s no reason you shouldn’t. I later find out the way to the parish church, named for St. Louis, Bishop of Toulouse. Exit U.S. 101 at Broad Street and go west. Turn right on Lincoln Street, then right on Choor Street and right again on Palm Street. Mission San Luis Obispo de Tolosa is on the left.)

Miles and Miles of Croplands

Just beyond the town of Paso Robles, where wineries beckon tourists to stop and taste, I discover Mission San Miguel Arcangel is closed due to damage from a 6.5 earthquake (it hit on December 22, 2003). Most of California’s missions have been partially or wholly destroyed by fires, floods, earthquakes, attacks, neglect or any combination.

A few miles up the road, I take the G18 exit to Jolon, which is so small, I’m not sure I saw it. Mission San Antonio de Padua is in the middle of the Fort Hunter Liggett Military Reservation. After presenting my driver’s license to a soldier at the gate, I drive a couple of miles and then, there it is, all alone in the middle of nowhere. I am absolutely certain I have just traveled back into another time.

Mission Nuestra Senora de la Soledad is also difficult to find due to poor and non-existent signs. I zig and zag on the G-roads until I’m dizzy. Once I find it, I am welcomed by a delightful docent named Paula Sarmento and a fat feline named Olivia, the Queen of the Mission. Destroyed by a flood and an earthquake, the mission was rebuilt in the 1950s by the Native Daughters of the Golden West.

Paradise Found

Instead of getting back on the 101 and heading north to Carmel, I take G16, a windy road halfway between the ocean and the agricultural fields of the Salinas Valley. I’m in awe of the changing terrain: tall buttes, deep gorges, gentle hills and grassy valleys.

Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo has magnificent gardens and vine-covered doors. In 1818, when Hippolyte Bouchard, a pirate sailing under the Argentine flag, sacked Monterey, the mission used its resources to help the homeless and rebuild the city. In 1852, when a neglected roof caved in, Joaquin Murietta, the Robin Hood of El Dorado, hid in the ruins.

Taking Highway 1 north to the 156, I travel inland to Mission San Juan Bautista, which overlooks the original El Camino Real. Across the quadrangle is the Plaza Hotel (1814), which later became a famous stage stop, nestled among other buildings of historic interest. This is the last mission in the chain that isn’t plagued by traffic and congestion.

The End of the Trail

Backtracking to Highway 1 and again heading north, I find Mission Santa Cruz. It’s a 20th-century replica in the center of a very busy town. The ruins of the original mission can be found across the street.

The Mission Santa Clara de Asis is inland on the grounds of the University of Santa Clara. During the war with Mexico, this mission held the families of Col. John C. Fremont and his battalion while they headed toward Los Angeles, unaware that Don Francisco was marching on Santa Clara.

Mission San Jose de Guadalupe, on the highway to Oakland, hosted Jedediah Smith, the famous American trapper, mountain man and explorer. Next I travel to Mission Dolores, which is at 16th and Dolores Streets in San Francisco. Then to Mission San Rafael Arcangel, which began as a sanitarium. Mission San Francisco de Solano, the last mission to be built, is in Sonoma, 30 miles north of San Francisco.

The End of a Dream

A number of factors contributed to the missions’ decline: Mexico winning its independence from Spain; corrupt Mexican governors; and supplies being cut off, leaving the missions to support not only their own but soldiers and civilians, as well. Other contributing factors included Indian rebellions, California’s independence from Mexico, the California Gold Rush, natural disasters and neglect.

Women Preserving History

In 1892, Anna Pitcher, director of the Pasadena Art Exhibition Association, proposed preserving El Camino Real but couldn’t find any support. A decade passed before two groups came forward: the California Federation of Woman’s Clubs (CFWC) and the Native Daughters of the Golden West. In 1904, El Camino Real Association was formed and began studying ways to reestablish the route. Mrs. A.S.C. Forbes (CFWC) created the now famous cast iron bell that hangs from an 11-foot bent guidepost. The marker served well, as it awakened public awareness to the historic route and its many branches.

The first bell was dedicated on August 15, 1906, and placed in front of the Old Plaza Church in downtown Los Angeles. Although the bells completely marked the route by 1913, many of the originals have been stolen or vandalized, and need to be replaced. The route should have 555 new bells erected in time for this year’s centennial anniversary of the marker. Look for the bells during your trip along the Royal Road.

Photo Gallery

– All photos by C. Clarke –