On the first day of summer in 1850, John Beck, a Cherokee preacher en route to California’s goldfields, stopped to do a little panning along the Front Range of the Colorado Rockies near what would become Denver.

On the first day of summer in 1850, John Beck, a Cherokee preacher en route to California’s goldfields, stopped to do a little panning along the Front Range of the Colorado Rockies near what would become Denver.

He found a few flecks of color, but he didn’t think the stream would pay adequately for his efforts, so he continued on toward California.

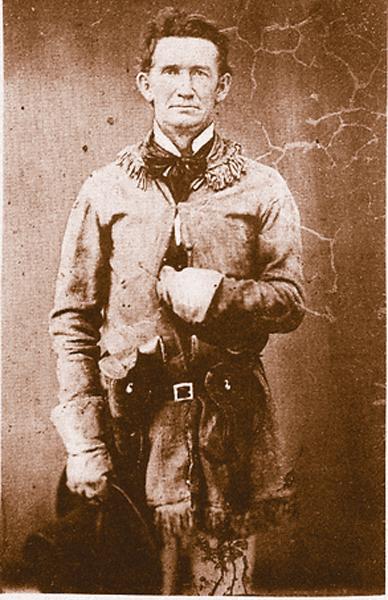

A few years later, Beck had left California and corresponded with William Green Russell in Georgia, who had also been in California during the gold rush, and the two organized a return trip west in the spring of 1858. They struck out along the Cherokee Trail, adding new members to their gold-seeking party until it numbered 104 prospectors by the time they stopped at what became Cherry Creek on June 24, 1858. Success didn’t happen overnight, and by July 6, only 13 men, including Russell, were present when they found color in their gold pans.

At the same time, a group of men from Lawrence, Kansas, who had heard about the gold from Fall Leaf, a Delaware Indian who saw it while on a military reconnaissance in 1857, also headed west. They reached Pike’s Peak a couple of weeks after Russell’s party had stopped farther north. The Lawrence men hunted and searched for gold, to no avail.

Russell’s men tried to keep their find quiet, but on August 26, word of their discovery hit the newsprint of the Journal of Commerce in Kansas City:

THE NEW ELDORADO!!!

Gold in Kansas Territory!!

The Pike’s Mines!

First Arrival of Gold Dust in Kansas City!!!

Mountain trader James Bordeaux brought the news from the diggings when he returned to Kansas City to obtain tools and outfits necessary for working the gold-laden streams. “They bring several ounces of gold, dug up by the trappers of that region, which, in fineness, equals the choicest of California specimens,” the Journal of Commerce reported.

“Mr. John Cantrell, an old citizen of Westport, has three ounces which he dug with a hatchet in Cherry Creek and washed out with a frying pan,” the paper added.

Soon, word of the Colorado gold had been published in St. Louis and Boston newspapers and the rush was on as people threw their mining tools and supplies into wagons, tied on signs that said “Pike’s Peak or Bust!” and headed west. At that time gold had not actually been found on Pike’s Peak, or even nearby, but that was the most recognizable point and it became the identifying landmark.

Unsuccessful farther south, the Lawrence party moved north and organized the Montana Town Company on September 7, 1858, but they abandoned it within a year. Some Lawrence men also organized the St. Charles Association on September 24, and with it a town site on the South Platte, about five miles from the mouth of Cherry Creek. Meantime, the Auraria Town Company organized on Cherry Creek on October 30, and then the Denver City Town Company organized on November 22. Before long Auraria and Denver were the strongest rivals, eventually merging into Denver City, the name coming from Kansas Gov. James W. Denver. It then became the central commercial hub for all gold seekers.

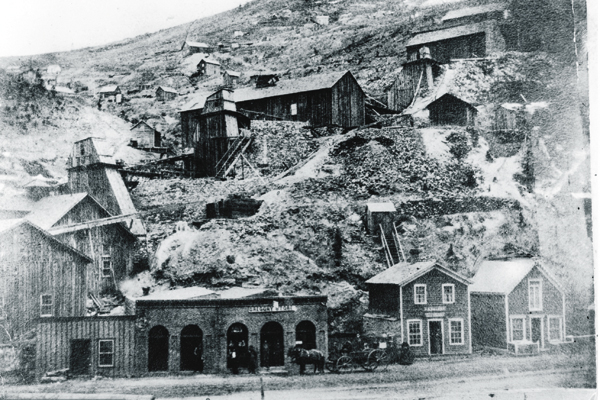

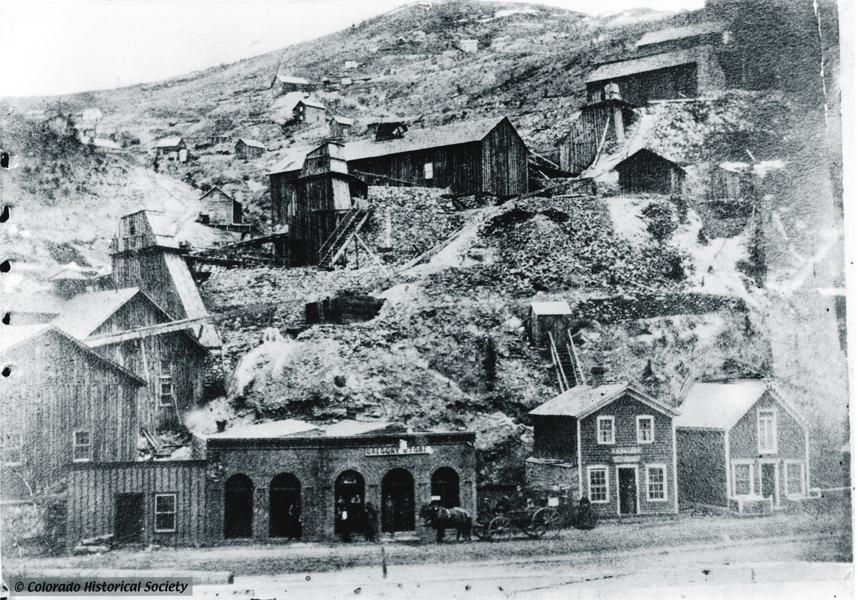

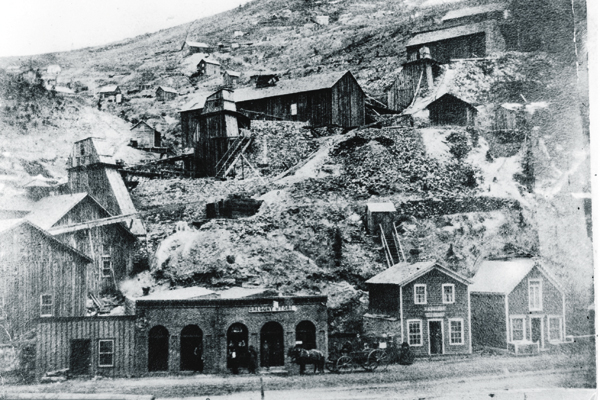

Gregory Gold Strike

In January 1859, independent miners struck gold in three additional locations. George A. Jackson on the 7th, while hunting for deer, found gold in Chicago Creek, as it entered Clear Creek at what became Idaho Springs. John Gregory found gold in mid-January near Gregory Gulch at what became Black Hawk. Six men struck gold on the 16th at the mouth of Boulder Canyon at the foot of Gold Hill.

By June 1, Gregory Gulch “was crowded with canvas tents, log shanties, and bough houses, as thick as they could stand…. The more recent arrivals began to murmur about the first comers—none of them had been here a month yet—monopolizing everything, and contended for a re-distribution of claims … cutting them down to twenty-five feet each,” Ovando J. Hollister wrote in 1867.

New York Tribune Editor Horace Greeley visited the Gregory Gulch diggings on June 6. Three days later, the “Greeley Report” appeared as an extra in the Rocky Mountain News. “We have … seen the gold plainly visible in the riffles of nearly every sluice, and in nearly every pan of the rotten quartz washed in our presence,” Greeley wrote. That sealed it. There were riches beyond belief in the mountains and their clear streams. Or so the miners who began rushing to the area thought. To their credit, the journalists made some attempt to head off the stampede, writing, “We charge those who manage the telegraph not to diffuse a part of our statement without giving substantially the whole; and we beg the press generally to unite with us in warning the whole people against another rush to these gold-mines, as ill-advised as that of last spring.”

Greeley, in a June 11 letter to the New York Tribune, added, “As yet the entire population of the valley sleeps in tents or under booths of pine boughs, cooking and eating in the open air. I doubt that there is as yet a table or chair in these diggings, eating being done around a cloth spread on the ground, while each one sits or reclines on mother earth.”

Other strikes followed on Boulder Creek and then prospectors moved into South Park, closer to Pike’s Peak, where they struck pay dirt on Tarryall Creek. On August 13, the Rocky Mountain News reported: “Five days ago the rush began for South Park; ever since[,] a continual stream of miners have passed through our streets. Wagons, carts, pack animals and footmen—all heading one way; all bound for the same destination—the head waters of the Platte.” Some of the prospectors who didn’t find good claims on Tarryall Creek said the stream should have been “Grab All.” Later when those same miners found gold farther west, they named their camp “Fairplay,” attempting to show that their practices and policies would provide equal opportunity for all gold seekers.

A Mining Outfit

The miners who flocked to the region came primarily from four states: Ohio, Illinois, New York and Missouri, which sent around 4,000 residents. Smaller numbers came from Connecticut, Indiana, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Virginia and Wisconsin.

When newcomers reached the gold camps, they found supplies limited and expensive. Much of the early trade came up the well-established Trappers Trail from Taos, New Mexico. One man noted, “Flour is worth $12 per sack, 100 lbs. Groceries are rather scarce.” Another added, “Bacon is worth 50 cents, flour $15 per barrel, as they get it from Taos, New Mexico, which is 300 miles from Cherry Creek.”

Early arrival Alexander O. McGrew, on November 20, 1858, outlined plenty of business opportunities: “a good drug store, a hardware store with plenty of building materials, a printing office with a good job office attached, clothing and dry goods; in fact, a general assortment would do a good business. Sheet iron is in demand; lumber is worth fifty cents a foot, so that a good saw mill, shingle machine and lath cutter would do a good business. A daguerreotypist could make his fortune here at present…. Let mechanics who anticipate coming bring their tools, as wages will be high.”

Prospector E.C. Mather, perhaps having little luck in mining but seeing the prices of food, advised, “come out in the spring as early as possible, and be sure and bring a plow, and a supply of seeds, bring a light plow as the soil is very loose and sandy, it is well adapted to raising wheat and corn; there can be fortunes made in farming.”

In their Complete Guide to the Gold Districts of Kansas & Nebraska published in Chicago on January 11, 1859, Edwin R. Pease and William Cole wrote, “A company of four can supply themselves with all necessary articles for mining, and provisions for from five and a half to six months, including two yoke of oxen and one wagon, for $140 per man, and a company of six for $120, including fares and freights from Chicago or St. Louis to [Leavenworth] City. Good oxen can be bought for from $65 to $80 per yoke and a good wagon from $75 to $80.”

Pease and Cole also noted that miners could travel by stage “running regularly to the mines from Omaha City early in the spring, carrying through passengers to the mines for one hundred dollars each, including meals and fifty pounds of baggage.”

As might be expected, there were conflicts over the value of gold. Generally, a pinch between the thumb and forefinger was valued at 25¢ while larger amounts were weighed on a scale to determine value, but gold dust stuck to scales, fingers, thumbs and even in the pouches miners used to transport it. To resolve differences, Clark, Gruber and Company of Leavenworth, Kansas, established a banking house in Denver in 1860 and began minting $10 gold pieces, later also striking gold coins valued at $2.50, $5 and $20.

If You Don’t Find Gold, then Goback!

About 90 percent of the estimated 100,000 prospectors and miners who sought riches as part of the Pike’s Peak gold rush weren’t successful, and they soon departed the region. There were so many returning to their homes that they became known as “Gobacks.” Indeed, some never even made it to the mining region before turning tail.

Goback J.M. Newhall of Lawrence, Kansas, told of his venture in an article for The Kansas Magazine, published in Topeka in 1873:?“About the first day of March, A.D. 1859, four of us started for the Pike’s Peak gold diggings…. There were no regular ‘diggings’—nobody digging for gold—that we could see…. I shoveled often in the river bed—got lots of shining stuff; but … all is not gold that glitters…. We wanted to stay because we were ashamed to go back home flat broke.”

Eventually Newhall did start toward home in Lawrence, later writing, “On I rolled, meeting teams once in a while, and among others the famous one chalked in letters more than a foot long across one side of his covered wagon, ‘Pike’s Peak or Bust!’ ‘Busted by G—d!’ was not on the other side at that time.”

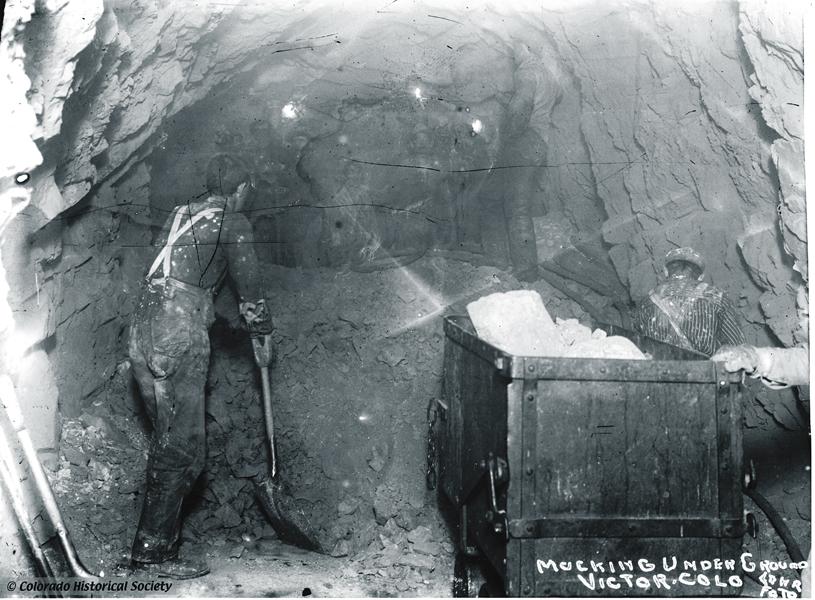

As with most mining booms, the early rush to Colorado settled into a sustained flow, then withered before additional gold and silver claims focused attention on the region once again as new boomtowns sprang up at Cripple Creek, Leadville, Georgetown and many other locations. During the latter half of the 19th century, millions of dollars in both gold and silver came from the cold streams and underground veins of Colorado. Mining continued into the 20th century, and places like Cripple Creek still have active gold mines in operation.

Candy Moulton makes her home near Encampment, Wyoming, when she isn’t on the road seeking out information for articles about the American West.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Colorado Historical Society, CHS.J653; By William Henry Jackson –

– Courtesy Colorado Historical Society, CHS.X7582; By W.H. Reed –

– Courtesy Colorado Historical Society, CHS.X6594; By Bill Lehr –