I loved to go to my grandmother’s house. She loved to cook, and she would sing and hum while she fried up the best potatoes and eggs you have ever tasted.

I loved to go to my grandmother’s house. She loved to cook, and she would sing and hum while she fried up the best potatoes and eggs you have ever tasted.

She also made knockout cowboy beans. (Even though she taught each of her five daughters how to do the same, each daughter’s pinto beans had a slightly different taste—all good—but my grandma’s were the best.)

I also liked to spend the night there because she and my step-grandfather, Ernie, had added on a room in the back, which had no heat. I would pretend I was a cowboy in a line shack way out on the range, and that was a definite plus in spending the night there.

One night, before I went to sleep, I heard cars racing up the street behind us. Then I saw lights raking off the ceiling of the little room, followed by the sounds of sirens, car doors slamming, loud voices and men talking. After a long while, the talking died down and the lights raked back across the ceiling and disappeared.

I found out in the morning that hotrodder T.J. Stockbridge, a shirttail cousin, had eluded the police and was hiding out behind my grandmother’s barn. That was very outlaw cool to me.

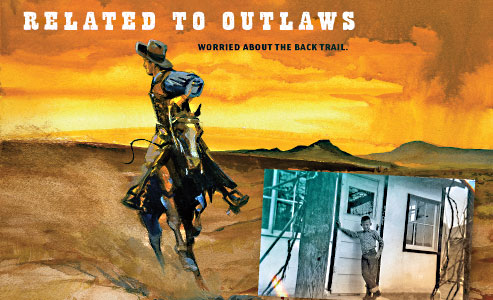

What was even better, however, was how my grandmother would get out all her old photos from a large box and tell me stories about all of our outlaw kin. She told of rustlers and train robbers and all kinds of bad men who resided on the outer edges of the law. Famous outlaws, she said, came in the middle of the night, leaving a winded horse and taking another. Sometimes, the horse they left was better than the one they took.

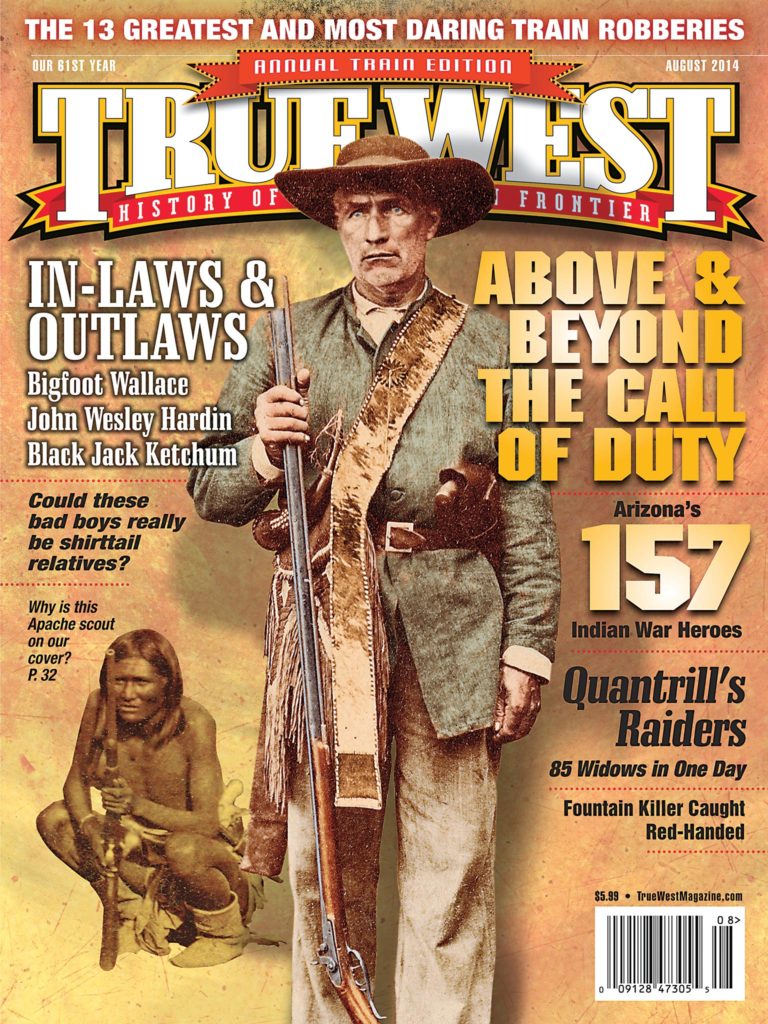

While all this thrilled me to no end, my mother hated it. And it drove her crazy when I’d tell other people about being related to outlaws. When I said we were related to Bigfoot Wallace, John Wesley Hardin and Black Jack Ketchum, what she heard was Jack the Ripper, the Boston Strangler and Charlie Manson.

My Grandmother Disses Wyatt Earp

Of all the story times at my Grandma Guessie’s house, one would have the most influence on me and my later career. My parents had gone to a dance at the American Legion, and while my grandmother regaled me with stories from the Old West, I was nervously watching the clock. My favorite television show came on at seven, and I didn’t want to miss it. I finally asked if I could turn on the TV, and she said I could. I rushed to the TV and turned it on, just in time to hear the lyrics to the theme song:

Wyatt Earp, Wyatt Earp,

Brave, courageous and bold.

Long live his fame,

And long live his glory,

And long may his story be told.

Yes, the show was The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp, starring Hugh O’Brian. I loved the show because Wyatt Earp cleaned up every cowtown in the West; he was a bachelor, he drank milk, and he had a very long pistol with a barrel that went all the way to the ground. He could write his name in the dirt with the barrel of that gun.

Well, right in the middle of that song, my grand-mother pointed at the TV and said: “Wyatt Earp was the biggest jerk who ever walked the West.”

I was stunned. Here I was looking at the TV, which never lied, and my grandmother, and I thought, “Wow, someone is not telling the truth here.”

I didn’t know it at the time, but the fuse had been lit. It would take another incident, a few months later, to crystallize my passion for finding out the truth about all the Old West outlaws and lawmen.

And it happened on Route 66.

The Buy of a Lifetime

For more than two decades, our family hit the road late each summer on the same stretch of road between Kingman, Arizona, and the Bell family farm north of Thompson, Iowa. Every year we followed the same regimen: up at 4 a.m., on the road by 5 a.m., drive for an hour or so, and then stop for breakfast (invariably at the Copper Cart in Seligman). My dad always ordered the same thing: bacon and eggs, coffee and orange juice.

Most cars going west had inner tubes on the top, vacation stuff, and the people were smiling and excited. They were on their way to Disneyland and the beach. We were Norwegians on our way to the family farm, and we were determined to get there so we could eat five times a day and talk about crops.

As the country rolled by, I stood on the transmission hump and gazed over the wraparound windshield at what my friend (and fellow Kingmanite) Jim Hinckley calls “America’s longest sideshow.” Long signs that traversed an entire mesa tempted us with tantalizing come-ons: “World’s Largest Buffalo!”

“Can we stop Dad?” Zarrooooom. We blew by there without even slowing down. “Gotta make time,” he’d say gravely.

When we got into New Mexico, I saw the sign “Live Indians.” I was hooked.

“Dad?” Zarrooooom.

In Santa Rosa, my heart leaped: “Billy the Kid’s Grave: 54 miles.” Zarroooom.

I finally realized Dad wasn’t going to stop for anything except gas, food and maybe open wounds.

After we got to Iowa—and we’re eating our fifth meal of the day, at the Hauans’s, as I recall—I asked if he’d let me choose just one place to stop at on the way home.

“We will, Kid,” he said, “if we have time.”

I knew what that meant. We were going to blast straight back to Kingman, and he wasn’t stopping for anything.

So I hatched a devious plan.

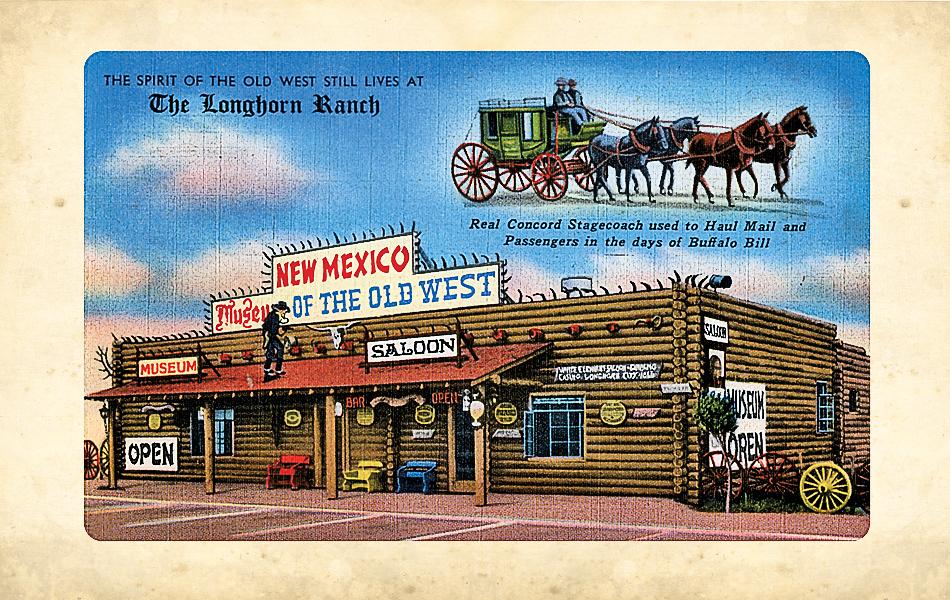

On the way to Iowa, I had picked out the place: 43 miles east of Albuquerque, New Mexico, on the south side of the road. The Longhorn Museum, it read, and it sat as part of a fantastic mini-street of Old West buildings. After breakfast in Santa Rosa at the Club Cafe, I went into action.

Every father has a weak spot, running from the ear down to the shoulder. You can discover it if you stand behind him while he’s driving and start poking him there, saying repeatedly, “You promised, Dad. Come on, you promised!”

Dad, of course, kept trying to shake me off, probably because he was in the process of passing 10 trucks. But I would not be denied. Finally, he swung that big, long ’57 Ford (with the continental kit on the back) into the dusty parking lot of the Longhorn Museum. He shut off the engine, turned to look at me in the back seat and said sternly, “Kid, you’ve got 15 minutes.”

The fantastic Longhorn Ranch Saloon and Museum loomed before me.

Those were the most precious minutes of my life. I ran in the museum, and there were all the things I love: saddles, longhorns on the wall, rifles and muskets everywhere. I was in a buying mood because my grandfather, Carl Bell, had given me a shiny quarter when we left the farm and headed west the day before, and told me to buy something special with it.

I asked the man behind the counter how much for a Flintlock rifle hanging on the wall. He said, “$100.” I said, “I’ll give you a quarter?”

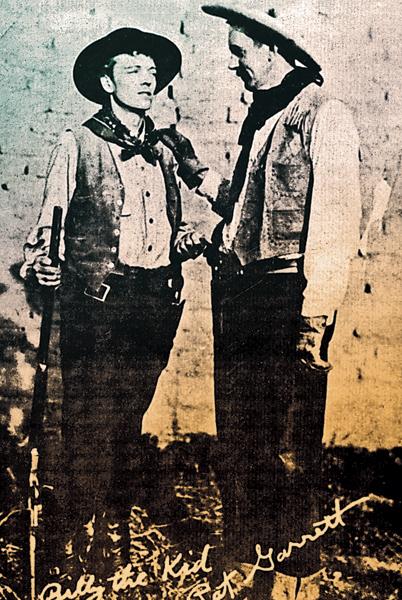

Then I saw it: “An authentic photo of Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid.”

The price? A quarter.

We got back in the car, and my dad blasted back out on Route 66 and floored it. He had to catch all the trucks that had gotten by him while we were in the museum.

Me, I was studying my authentic photo in the back seat. We fought our way through Albuquerque, then cruised around Laguna, Cubero, Grants and on into Arizona.

I was so quiet, my mother was concerned. “Are you alright?”

“Yes,” I assured her. “I am studying this authentic photo of Billy the Kid and Pat Garrett.”

I don’t even remember the rest of the trip through Sanders, Lupton, Holbrook, Joseph City, Two Guns, Flagstaff, don’t forget Winona.

When we got home, I put that photo on the wall by my bedroom door and studied it every day. I made a vow to someday have a rifle, hat, and vest exactly like the one Billy was wearing.

Two weeks later, I went with my mother to Desert Drug in downtown Kingman. While she was getting a prescription filled, I ran to the front of the store and bought the latest issue of True West. I took it out to the car to read, and on page 32, I discovered that the authentic photograph I had paid a quarter for was a FAKE! It had been taken at a parade in Santa Fe, New Mexico, in 1937.

I spent the rest of my youth—and a fair share of my adulthood—trying to find the real Billy the Kid. Thus began a lifetime obsession with Old West outlaws and lawmen.

It would take another 25 years to make it to Fort Sumner and the Kid’s grave for the first time.

The Ketchum Connection

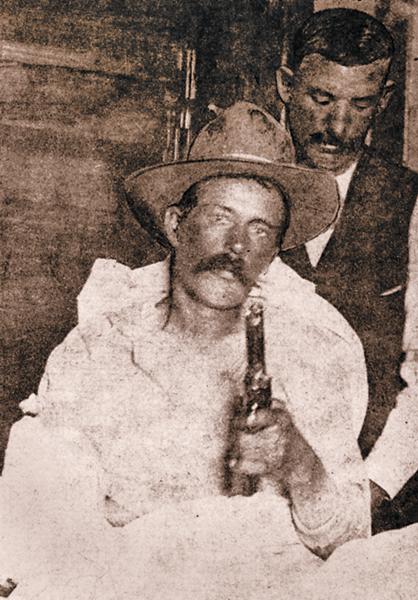

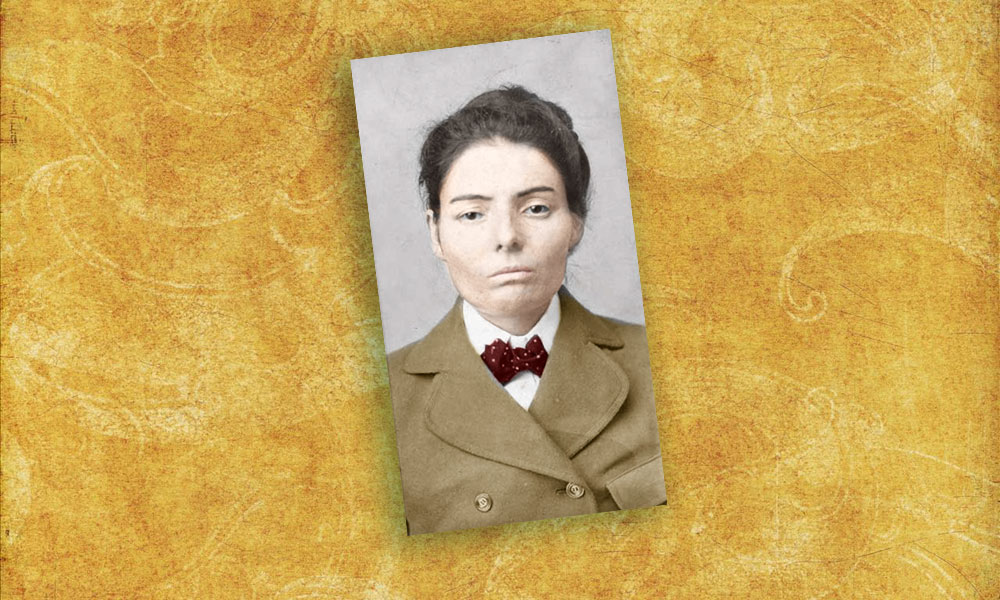

My grandmother regaled me with stories of our connection to not only Bigfoot Wallace but also Ketchum. That would be Black Jack Ketchum, the notorious train robber and member of the Wild Bunch who was hanged in Clayton, New Mexico, in 1901.

My grandfather Bob Guess came to Arizona’s Mohave County in 1912 to visit his grandmother in Hackberry. While there, he met legendary cowman Tap Duncan, who hired Bob to ride for one season with the Diamond Bar cowboys. Later, after a ranching career in the Bootheel of New Mexico and then on the Gila River near Duncan, Arizona, Bob was busted by the Depression. He returned to Mohave County in 1936, and his first stop was Tap’s Diamond Bar Ranch.

Bob now had a wife and five daughters. His oldest, Sadie Pearl, married Tap’s grandson, and that is how we are related to the Duncans. In 1879, Tap’s brother, Bige, married Nancy Ketchum, the sister of Tom “Black Jack” Ketchum. And that’s how we are related to the Ketchums.

Our connection to John Wesley Hardin came from my grandmother’s mother, Tiny Pickhart. She married a Hardin, in Texas, and they had a daughter named Rosie Hardin. Twisted stuff, but heady just the same for a nine-year-old boy.

Photo Gallery

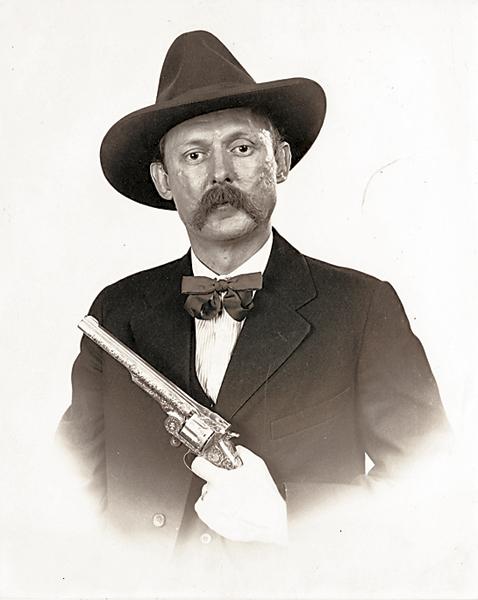

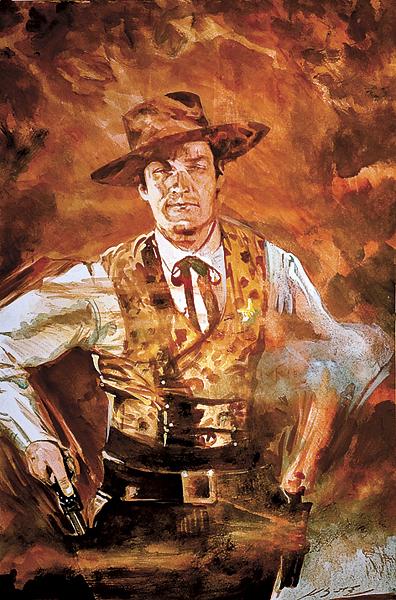

Black Jack Ketchum

Bob Boze Bell

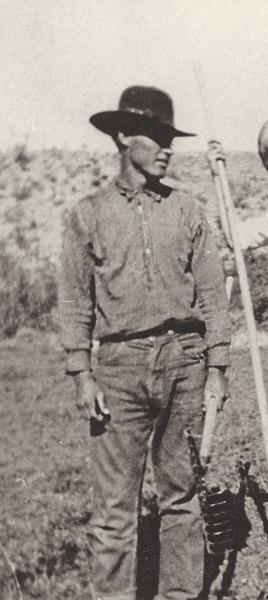

Bob Guess at the Diamond Bar

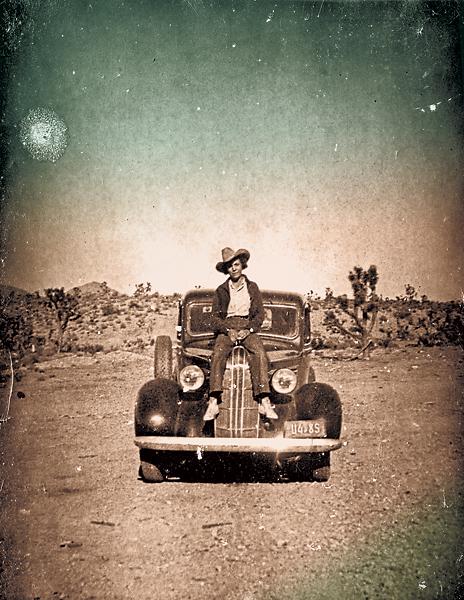

Bobbi Guess

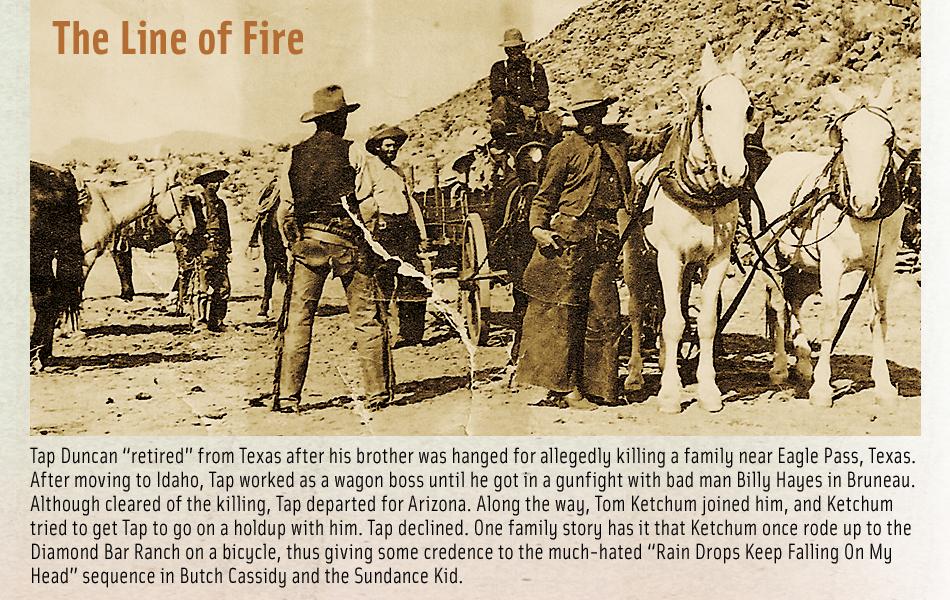

Tap Duncan “retired” from Texas after his brother was hanged for allegedly killing a family near Eagle Pass, Texas. After moving to Idaho, Tap worked as a wagon boss until he got in a gunfight with bad man Billy Hayes in Bruneau. Although cleared of the killing, Tap departed for Arizona. Along the way, Tom Ketchum joined him, and Ketchum tried to get Tap to go on a holdup with him. Tap declined. One family story has it that Ketchum once rode up to the Diamond Bar Ranch on a bicycle, thus giving some credence to the much-hated “Rain Drops Keep Falling On My Head” sequence in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

Tap survived the Wild Bunch (he was mistaken for gang member Kid Curry) and the Wild West, but in 1944, he was run over by a car just off Route 66 in downtown Kingman. He is buried in Mountain View Cemetery on Hilltop.

– All images courtesy bob boze bell –

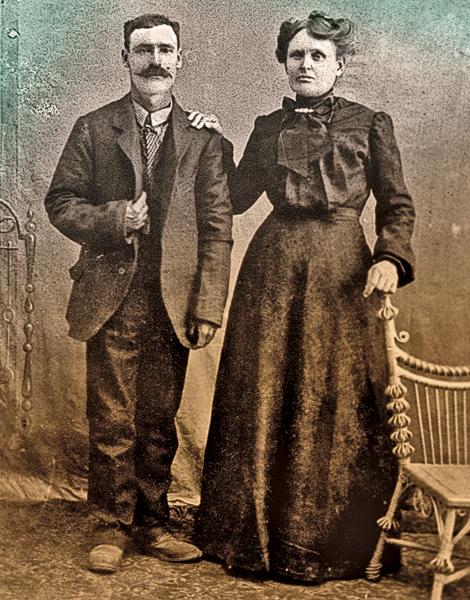

Tap Duncan