Are you here to see the Dakota War exhibit?” a male worker at the Minnesota History Center in St. Paul asks me.

Are you here to see the Dakota War exhibit?” a male worker at the Minnesota History Center in St. Paul asks me.

It takes a moment before I can answer. I didn’t expect anyone in Minnesota to be broadcasting the 150th anniversary of a war that most people here would just as soon as forget.

But, “Yeah,” I reply, and head upstairs to take in “The US-Dakota War of 1862,” which opened last June and closes on September 8.

This is an impressive, well-balanced exhibit, low on artifacts, but high on historic interpretation. It is a good start on an important Renegade Roads.

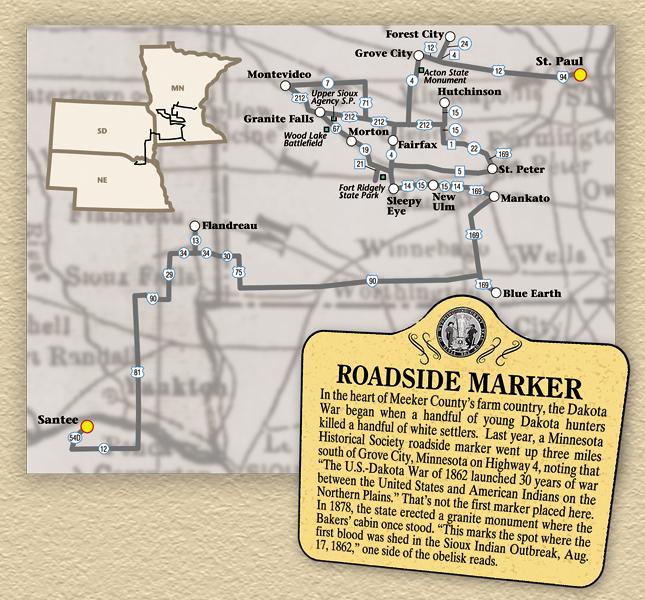

The Dakota War is said to have started in Acton, about a two-hour drive west. In reality, the war started much earlier.

Bad Times

By the time Minnesota entered the union in 1858, most American Indian lands had been ceded, and the Dakota were living on reservations. The Homestead Act of 1862 would send more white settlers into the state.

Now, stop me if you’ve heard this story before: Some Indian agents and traders were corrupt! Because of such corruption, annuity payments to the Indians were late. By August 1862, many Dakota were starving.

Months earlier, George E. Day had written his boss, President Abraham Lincoln, about the corruption rampant among Indian Affairs, but Lincoln was preoccupied trying to keep the Union intact. When Indians complained to white trader Andrew Myrick, he said, “Let them eat grass, or their own dung.”

On August 17, four young Dakota hunters, pretty much on a whim, murdered five white settlers in Meeker County near Acton Township. The young Indians fled to their village, begging for protection. Warmongers of the group appealed to the Dakota leader Taoyateduta, known to the whites as Little Crow, to lead the Dakota in a war against the whites.

Little Crow didn’t want to, but he did, and Minnesota almost went up in flames.

In about six weeks, an estimated 400 to 600 white settlers and soldiers were killed. Indian casualties are uncertain. The ending of the war is also ambiguous; it ended in September at Camp Release near Montevideo, or maybe in December in Mankato, or maybe on July 3, 1863, when Little Crow was killed while looking for berries in a farmer’s field near Hutchinson. Nathan Lamson collected not only a bounty for the dead Indian, but also a $500 bonus for killing Little Crow.

Or … maybe … the war still isn’t over.

John Koblas recalls a book signing for the first volume of his history, Let Them Eat Grass, when Dakota Indians protested a white man writing about an Indian war: “I told them I thought I was fair, that I told both sides of the story—as I always do— and that I was, and am, very sympathetic to Little Crow,” Koblas says.

The Minnesota History Center gives both sides of the story and doesn’t sugarcoat one thing.

This is a promising start.

Also in St. Paul, Fort Snelling State Park is a must stop, whether you’re following the Dakota War or you just like old forts. Established in 1819 and originally known as Fort Saint Anthony, the post would serve many soldiers fighting against the Dakota. After the war, some 1,600 Dakota were held at the nearby agency. The whites called it an internment camp. The Indians saw it as a concentration camp.

Loggers and Farmers

From St. Paul, drive to Forest City, a town established by lumberjacks in 1855. After the Dakota outbreak, Meeker County treasurer George Whitcomb arrived with guns and ammunition—a gift from the governor. Of course, by that time, only 13 men and three women remained in the town. Most had fled. In early September, Capt. Richard Strout and his company engaged the Dakota in the Battle of Acton. The Dakota numbered some 200. Strout lost six killed and between a dozen and two dozen wounded. That’s why you’ll find a reconstructed stockade at Forest City. Within a day after the Acton fight, the Home Guard and other settlers had built the stockade for protection, using timbers that had been cut to build a church. The stockade protected scores of settlers during the war.

This is farm country, and most of the settlers had come there to farm. In fact, the historical markers in Acton are found at a farm, on a dirt road off Minnesota Highway 4, south of Grove City. The plaque on a small rock that marks Little Crow’s death is next to a field off a county road about six miles north of Hutchinson.

Yet the Dakota War wasn’t just about attacks on farmers or at farms. Let’s swing by St. Peter. The Treaty Site History Center, home of the Nicollet County Historical Society, examines the 1851 treaty in which the Dakota Nation sold 24 million acres—roughly half of Minnesota—to the United States. The museum also covers the fur trade and Dakota culture. You can even hike along Traverse des Sioux, the shallow river crossing that made this an ideal meeting place for U.S. and Dakota officials to meet in 1851.

Fore! for Forts

From St. Peter, I’m off to Fort Ridgely State Park near Fairfax.

This tour is more along the lines of what I expected to find in Minnesota while touring the Dakota War sites. While I saw a few people at the Minnesota History Center, I have been alone at most of the other spots. Even the McLeod County Historical Society Museum was closed, though the hours said it should be open.

The only person I find at Fort Ridgely is a guy in a golf cart, who seems annoyed that I’m reading the markers, which is interrupting

his game.

We think of Indians attacking forts as something out of B-Western movies, but in reality these attacks did happen during the Dakota War. In 1862, the fort, then a training base for Civil War volunteers, was attacked by Dakota Indians—twice, on August 20 and August 22. Some 280 military and civilian defenders held out until Army reinforcements ended the siege. The Dakotas also attacked Lake Shetek, abducting women and children as their hostages.

Ridgely wasn’t the only institution the Dakotas attacked. Head over to Morton to visit the Lower Sioux Agency and Birch Coulee Battlefield Site.

Birch Coulee was among the hardest fought battles of the war. On September 2, 1862, Dakotas attacked a burial party of soldiers and kept the Army troops pinned down for 36 hours before Fort Ridgely reinforcements arrived. Today, the self-guided site offers perspectives from both Dakota and white viewpoints.

That’s near the end of the war. For a look at the beginning, head to the Lower Sioux Agency near Redwood Falls. Here, the Dakota War began in earnest when Little Crow’s forces killed 18 traders and government employees on August 18.

Among those killed here: Myrick. Remember him? According to reports, grass was stuffed in his mouth.

The Dakotas took their war to the people, attacking settlements and farms in Renville and Brown Counties, killing some 200 settlers and taking more than 200 white and mixed-blood hostages.

Today, the Lower Sioux Agency features numerous exhibits and interpretive trails. The same can be said of the Upper Sioux Agency near Granite Falls. The agency was evacuated on August 19. When the warring Dakotas reached the site, they destroyed most of the buildings. Today, the agency, now a state park, includes several trails, foundations and a restored agency house.

By this time, Gov. Alexander Ramsey had commissioned Henry H. Sibley to lead a volunteer militia against the Indians. As more settlers fled western Minnesota for the safety offered back east, the state was pretty much in panic.

Two Sides to the Story

The Upper Sioux Agency is a short drive to Wood Lake, where Sibley’s forces defeated Little Crow on September 23. Wood Lake is where I run into people, in fact, students from area high schools on a field trip. I was glad to hear that they were being told both sides of the story of the Dakota War.

Which, even today, doesn’t always happen. Because, after quick stops to Montevideo, where Camp Release basically ended the war, and Sleepy Eye (Sleepy Eye’s grave), I find myself in New Ulm. Indians attacked this town on August 19 and August 23, burning buildings along the river and destroying practically a third of the town. So I check into the Brown County Historical Society museum in downtown. “Never Shall I Forget: Brown County and the Dakota War” occupies the third floor. This is an amazing, moving exhibit, even if it is told predominantly from the white viewpoint. I have a hard time blaming New Ulm for that. After the uprising, the town wasn’t reorganized until December.

Having been defeated at Wood Lake, the Dakotas released white and mixed blood hostages at Camp Release on September 26, but that’s not the end of this story. That’s not why folks feel so much bitterness 150 years later.

To understand that, I’m off to Mankato.

Reconciliation?

Mankato is the place where, on December 26, 1862, thirty-eight Dakotas were hanged after being convicted by military tribunals of murder and rape during the uprising. The death toll could have been much worse. President Lincoln commuted the sentences of another 264 who had also been condemned to death, with one more, Tatemina, later given a reprieve because the testimony against him was deemed questionable. Still, many white settlers protested this clemency. Despite such popular outcry, Lincoln told Minnesota Gov. Alexander Ramsey, “I could not hang men for votes.”

Those 38 Indians who were hanged, on a single platform, would go down in history as America’s largest mass execution. Their bodies were buried on the riverbank; grave robbers dug up many of them.

By 1863, thousands of Dakota had been forced to South Dakota and Nebraska reservations. Most Dakota Indians today still live outside of Minnesota, but before taking off for today’s Dakota homelands near Flandreau, South Dakota, and Santee, Nebraska, I find myself in Mankato, at a place called Reconciliation Park.

The park is small. Again, I’m the only one here, walking around a 67-ton sculpture of a limestone buffalo as traffic buzzes along Riverfront Drive. The park was dedicated on September 19, 1997, at the site where those 38 Dakotas were executed. It’s a place of reflection, to come to terms with what happened 150 years ago, whether you’re white or Indian.

As Dakota Elder Amos Owen said in 1997, it is “a reconciliation for all people.”

Johnny D. Boggs recommends John Koblas’s three-volume history Let Them Eat Grass: The 1862 Sioux Uprising in Minnesota (North Star Press of St. Cloud).

Photo Gallery

– All photos by Johnny D. Boggs unless otherwise noted –

– True West Archives –