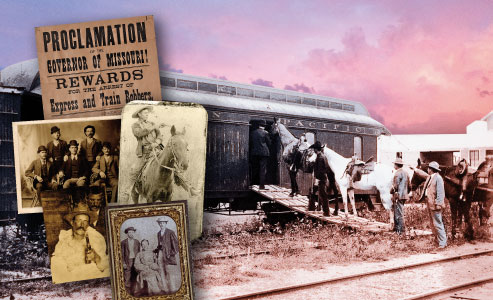

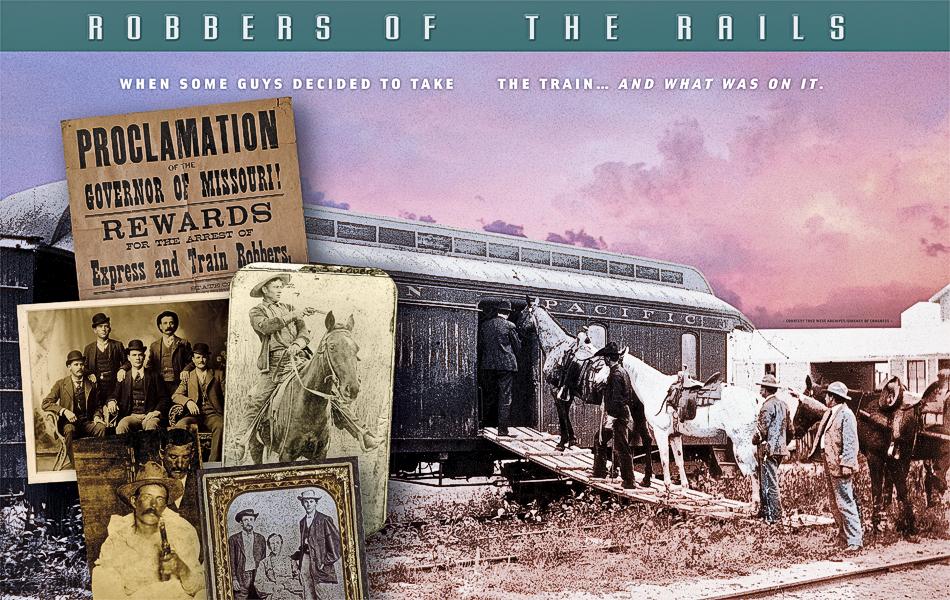

Face it—nothing says “Old West” quite like a good, old-fashioned, American train robbery.

Face it—nothing says “Old West” quite like a good, old-fashioned, American train robbery.

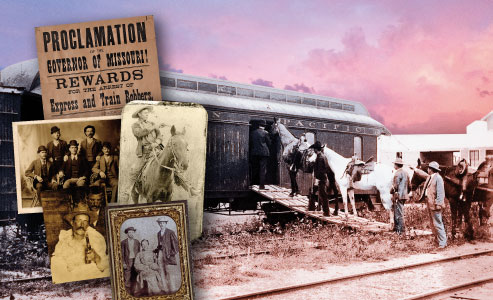

The image is burned in our brains: a gang of masked men stops the locomotive, holds passengers and crew at bay with gleaming .45s, blows the express safe with some well placed explosives, then rides hell-for-leather to safety astride the best horses money can buy (or that they could steal).

That’s not just a stereotype, sold by TV and movie Westerns and ink-stained wretches over the past 140 years. It really happened that way … more or less.

Take the first train stick-up in U.S. history, nearly 150 years ago—which didn’t happen in the West.

It was just after 8 p.m. on May 5, 1865, and the Ohio & Mississippi train was a few minutes out of Cincinnati, headed for St. Louis. At a remote location near North Bend, Ohio—in sight of the Ohio River and almost to the Indiana line—the train went off the tracks; somebody had pulled one of the rails.

The engine, express and baggage cars tipped over. The passenger cars stayed upright but several of the riders were injured. An estimated 15 to 20 desperados jumped aboard, firing their pistols and ordering everyone to shell out. Five of the outlaws went to the express car and used gunpowder to blow open the safes.

After about an hour, the robbers left—taking skiffs to cross the Ohio into Kentucky, where they mounted horses and rode away. Nobody knows the exact take, although some reports said they got up to $30,000 in government bonds and bank notes and several thousand dollars in cash and valuables from the passengers.

Federal troops pursued the thieves (technically, the Civil War was still on and civilian authorities lacked the power to cross state lines, especially into a border territory like Kentucky). For some reason, though, they didn’t head out for eight hours; some stories say the Union officer in charge had to be sobered up before they could start the chase.

When the posse got to Verona, Kentucky, they found that the robbers had celebrated with wine, women and song—there were even some stolen bank notes dropped in the streets. But the gang was never caught; the crime remains unsolved.

The North Bend train robbery set the standard for the countless railroad stick-ups that took place over the next 60 years.

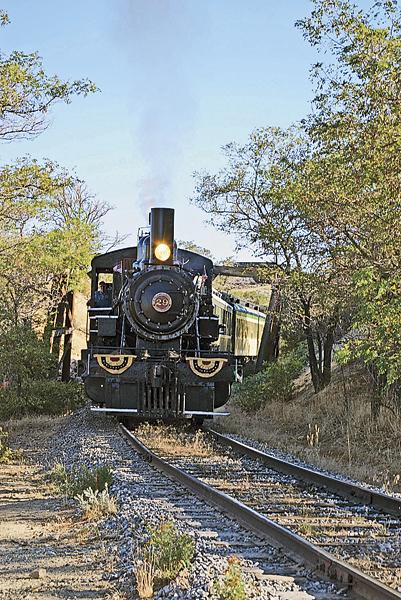

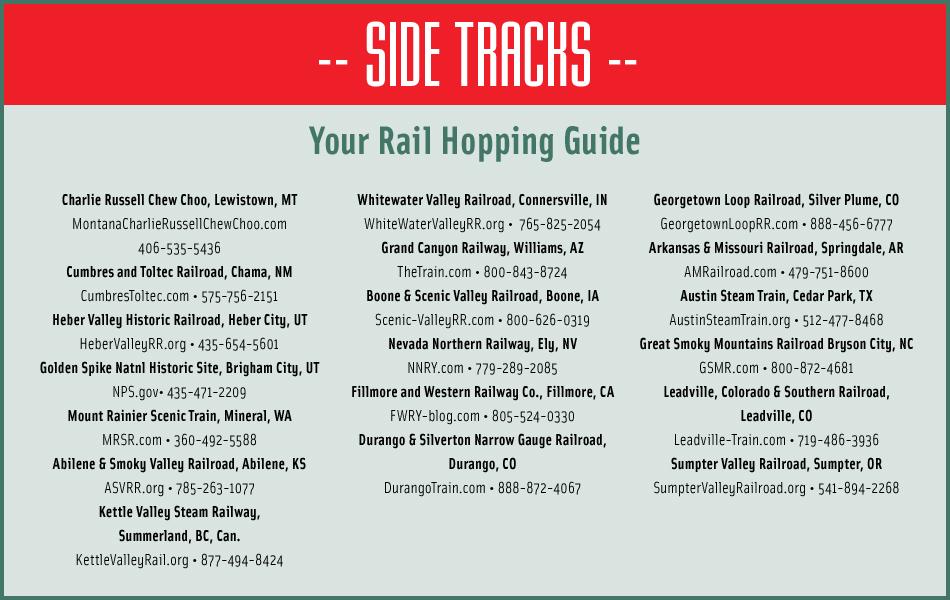

Some of those historic train lines are still in operation (as well as several that never suffered the indignity of a hold-up). They keep the Old West alive in interesting, informative and fun fashion.

Seeing as we’re talking about some of those railroads, it seemed appropriate to tie those in with some of the more interesting train robberies in Old West history.

So climb aboard—and hide your valuables!

Robbing the Rails from the Mountains to the Plains

Iowa

The first train robbery by the James-Younger Gang had some success and some failure—and showed just how little the outlaws knew about gold and silver bars.

It happened on July 21, 1873, and involved the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railway about three miles east of Adair. As the train went around a bend, an unseen hand pulled one of the rails. The engine, tender, baggage and express cars went off the track and rolled down an embankment, killing the engineer and injuring several passengers.

Three masked outlaws jumped into the express car, while two others held guns on the passengers and crew. The leader (who yanked off his mask) got into the safe and removed its contents, but kept asking, “Where’s the bullion?” The postal clerk pointed to more than a ton of gold and silver bars underneath … but it didn’t compute with the bandit chief, who apparently thought bullion was coinage. It wouldn’t have done much good if he had understood what the term meant—the gang hadn’t brought a wagon to haul the bars away.

So the outlaws got about $2,300, not millions. They didn’t rob the passengers (which they would do in a couple of later train jobs). As they left, the leader expressed regret over the death of the engineer. The gang mounted horses and headed for Missouri. There were no arrests, although the St. Louis police identified the robbers as Frank and Jessie James, Cole Younger, George Sheppard and Arthur McCoy.

Descriptions of the outlaw chief matched Jessie James to a “t.”

Colorado

The November 3, 1887, robbery of a Denver & Rio Grande train near Grand Junction, Colorado, is the stuff of legend. The legend being that it was the first big criminal act by Butch Cassidy (along with pals Tom McCarty and Matt Warner).

Nice story. But here’s what happened.

The train was about five miles east of Grand Junction when it ran into a pile of rocks blocking the tracks. When the locomotive stopped, three masked men entered the express car, while another held a gun on the engineer.

Express messenger Dick Williams had guts. The robbers gained easy entry to a small safe (with almost nothing in it). But when they ordered him to open the larger safe, Williams told them he couldn’t, that it could only be unlocked at the destination. They threatened to kill him; he continued his bluff.

The outlaws finally accepted his ruse and left, getting only about $150 in change and jewelry.

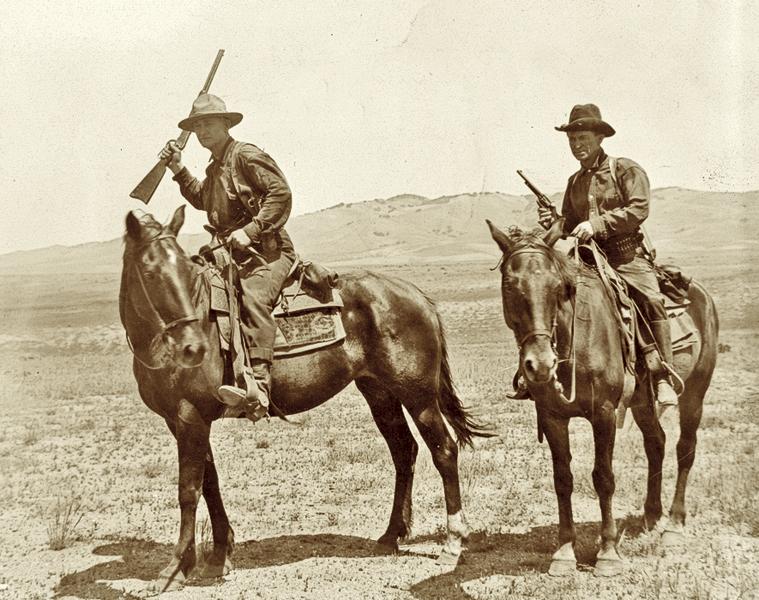

The railroad put up a $3,000 reward for capturing the outlaws, and the U.S. government tossed in another $1,000—a very big total for the time. It had the desired effect, pushing several lawmen to go after the robbers. Gunnison County Sheriff Doc Shores, who had a reputation as a dogged pursuer, was among them.

Eventually, Shores and his deputies caught up with the four men in Utah; they confessed and did prison time for the job.

But Bob Smith, Bob Boyd, Ed Rhodes and Jack Smith were definitely not Butch Cassidy and the Wild Bunch. The Hole-in-the-Wall guys were still a few years away from troubling the trains.

Wyoming

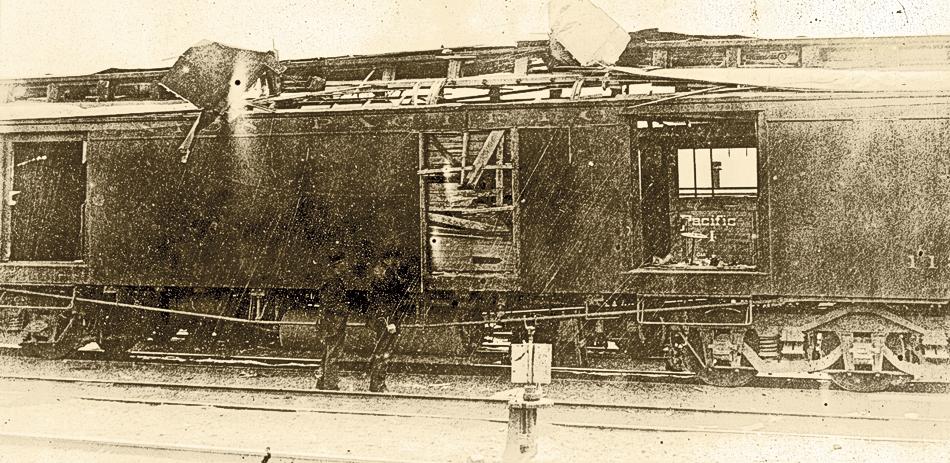

You’ve seen the movie: Butch and Sundance rob the Union Pacific Flyer near Wilcox, Wyoming, but in trying to open the safe they blow the express car to smithereens.

It’s a great scene, but it didn’t exactly happen that way.

Sure, members of the Wild Bunch did stick up that train on June 2, 1899. And a bit of mayhem ensued. But Butch wasn’t there—Harvey Logan (Kid Curry) led the Sundance Kid and George “Flatnose” Currie in the heist.

It started at 2:18 a.m., when two masked men, using red lanterns, flagged down the train. The forced the engineer to take the locomotive, tender, and express and mail cars down the track while they dynamited a trestle behind them. They then blew open the door of the express car, knocking the messenger unconscious (a third outlaw had joined them at this point).

That was when they tried to open the safes. And they used too much explosive. And the express car was blown to pieces. The robbers then grabbed an estimated $50,000 in bank notes and currency—all of which were damaged in the blast, making them easy to identify.

What followed was one of the largest manhunts in the history of Wyoming, with dozens of lawmen in various posses going after the robbers (and attracted by rewards totaling more than $18,000). During the pursuit, the outlaws shot and killed Converse County Sheriff Josiah Hazen. But they eluded capture; justice would have to wait for the three bad men.

Stealing the Southwest

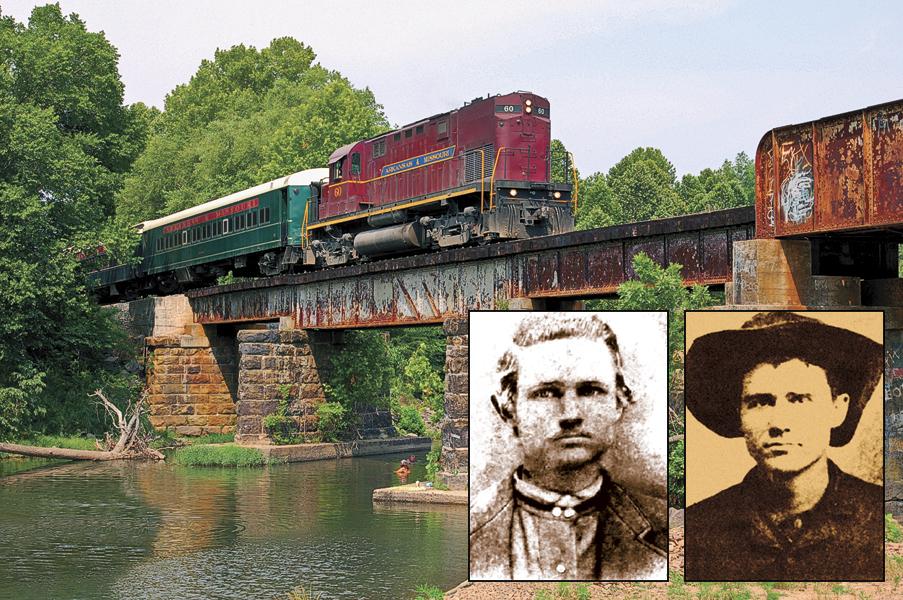

Arkansas

The Burrow Gang walked their way to and from a train holdup on December 9, 1887, at Genoa, Arkansas. Jim Burrow and Bill Brock boarded the St. Louis, Arkansas and Texas Railroad train just as it was leaving the station, ordering the engineer to stop a short distance away. That’s where gang leader Rube Burrow joined in.

The boys tried to get in the express car, but a Southern Express messenger wouldn’t let them in—even after they shot the door full of holes. He finally changed his mind when they started battering the door with a coal pick.

Inside, the bandits gathered up more than $3,000 in currency and silver before walking away with the loot—reportedly, some of it was from the Louisiana lottery. On this day, the Burrow outfit had the winning ticket—but only briefly. The trio hoofed it for Texarkana, Texas, about 30 miles away.

But en route, they got into a gunfight with a posse. The outlaws escaped, but left behind slickers and a hat. Pinkerton detectives traced one set of rain gear back to Bill Brock—and when he was arrested, he blew the whistle on his compatriots. Jim Burrow was arrested in his native Alabama and would die of tuberculosis in jail the next October. Rube continued down the outlaw trail for another couple of years. He was arrested in October 1890 and gunned down during an escape attempt on December 8—one day short of the third anniversary of the Genoa holdup.

Oklahoma

The Jennings Gang was probably the most idiotic criminal enterprise in the history of the West. Or East. Or South. Or North.

Al Jennings was a lawyer and former prosecutor, but in 1897—after some setbacks—he and his brother Frank went to the dark side. It did not go well.

On August 16, 1897, a couple members of the gang boarded the Santa Fe train at Edmond. They forced the engineer to stop about a mile away, where three of their compadres were waiting.

The gang went to the express car but had no idea how to get into the safe. They tried to shoot it open; they tried to blast it open. Nothing worked. They finally started robbing the passengers, but most of those folks had already hidden their money and valuables. The gang came away with just a few dollars.

It didn’t get any better after that. On two occasions, they attempted to flag down trains targeted for robbery, only to have the engineers try to run them down. They hit a small store and got $15. Overall, it is estimated the total haul for the Jennings Gang was less than $1,000.

The outfit quit the owlhoot trail around November of that year. Lawmen tracked them down and arrested the Jennings brothers—Frank got five years, Al was given life (!) but was pardoned a few years later.

Al then headed to Hollywood, where he wrote some books and made a few movies and consulted on others. And he told tall tales about his exploits as an Oklahoma outlaw.

Texas

In the Old West, sometimes the good guys were also the bad guys.

Jim Garlington was a bank robber who wanted to diversify. So he decided to hit the Santa Fe Railroad train at Saginaw, Texas, about 12 miles north of Fort Worth.

For whatever reason, Garlington decided to share his plans with Fort Worth’s Assistant Police Chief H.D. Grunnells. The cop seemed to be going along with the plot, although in reality he was setting up the old double-cross; he was going to arrest the gang during the robbery. Grunnells would be the hero in that scenario, of course, and be honored and feted for his master police skills.

It didn’t work out that way.

It was the evening of July 21, 1898, when the outfit boarded the train at Saginaw. A little farther on, Garlington—trying to get into the engine cab—accidentally fired his pistol. Other gang members opened up at the sound of the shot, killing the fireman and mortally wounding the engineer.

At that point, Grunnells and the police showed up, driving off the outlaws. Three of the bad guys were later arrested and one of them turned state’s evidence.

As a result of his testimony, Jim Garlington went to the gallows a year and a day after the botched holdup, convicted of killing the train crew members. Assistant Chief Grunnells was fired, then indicted by a grand jury for his role in the affair. But he went on the lam and never faced trial.

Pillaging in the Pacific Northwest

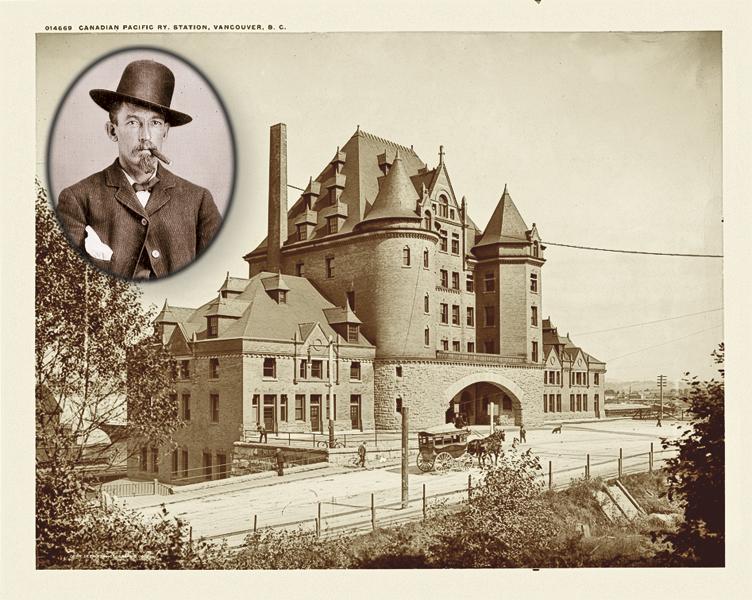

British Columbia

Bill Miner was 57 years old in 1904, a career criminal who’d spent a lot of years behind bars. But he just couldn’t give the life up.

He had relocated to British Columbia, and at about 9:30pm on September 10, he and two pals held up the Canadian Pacific Railway train some 40 miles east of Vancouver. In the express car they got $7,000 in gold dust and cash—and $50,000 in U.S. bonds and $250,000 worth of Australian securities. It was a huge score. And Wild West train robbery had come to Canada.

Despite being a suspect in the job, Old Bill stayed in Canada, taking it easy for a couple of years except for one foray to Washington State for another train holdup in 1905.

But in 1907, he decided to pull another job north of the border. He and two men held up a Canadian Pacific train about 16 miles east of Kamloops at 1am on April 30. This one didn’t go well. Miner and co. only got $15.50—and hot pursuit from the law.

The three were arrested on May 14. Miner was eventually sentenced to life behind bars, but he told the court that “no prison can hold me.” And he did escape that August, heading to the U.S. for more crime and jail time.

Interestingly, Bill Miner became something of a folk hero in Canada, noted for his kind and gentle ways as well as his anti-authoritarian attitude.

Washington State

In many cases, professional train robbers stayed away from holding up passengers. It took too much time and didn’t result in much loot. Leaving the passengers alone was also a good public relations move, allowing the outlaws to say they robbed the railroads or express companies but not average folks.

For whatever reason, the guys who pulled the first train stick-up in Washington did just the opposite.

On November 24, 1892, three masked men boarded a Northern Pacific sleeper pulling out of Green River Hot Springs, a tiny resort burg east of Seattle. One of the outlaws fired a shot through the ceiling of the car, adequately getting the attention of the passengers. When one of the male passengers protested, the same robber clubbed him over the head.

The bandits went through the car while the train continued on its way, demanding money and valuables. It’s estimated the take was worth about $2,000. But they had some compassion. T.C. Taylor asked for his 70 cents back, saying it would pay for his breakfast; one of the robbers handed him the change.

When they finished, they pulled the bell cord twice, which was the signal for the engineer to stop the train. They jumped off and ran into the night.

Some of the victims suspected that at least one of the robbers had worked on a railroad, but that was not confirmed. In fact, there’s no evidence anyone was ever arrested in the case.

Oregon

The D’Autremont brothers—Ray, Roy and Hugh—were amateur criminals. That cost the lives of four railroadmen in what may have been the last “Old West style” train stick-up.

The boys decided to hold up the Southern Pacific near Ashland, Oregon, on October 11, 1923. They had a plan—jump on the train while it slowly made its way through a tunnel in the Siskiyou Mountains, then blow the express safe and take the estimated $40,000 inside.

The first part of the plan went okay. The outlaws got on the train, forced the crew to stop and then prepared to get the money. But the express messenger wouldn’t let them in his car, so they used dynamite—blowing the car and messenger to kingdom come.

Then the train brakeman walked up to the outlaws, surprising them in the smoke from the explosion, and they shot him to death. The D’Autremont’s panicked, decided they couldn’t leave any witnesses, so they brutally killed the engineer and fireman. They then went on the run; they got not money from the disastrous incident.

And they stayed free for four years, until someone recognized Hugh D’Autremont on an old wanted poster. All three brothers were arrested, convicted of murder and sentenced to life in the Oregon prison. Hugh, Roy and Ray were each paroled at various points in their later years.

Their story and the account of the holdup were the subject of a book with a too right title: All for Nothing.

From California to New Mexico, Outlaws Rode the Rails

California

The Dalton Gang’s first foray into major crime was a major bust. On February 6, 1891, the boys tried to hold up the Southern Pacific train near Alila (now Earlimart), California, about 40 miles north of Bakersfield. Tried is the operative word.

It was dark when three men climbed onto the train and made their way to the locomotive, where they forced the engineer and fireman to stop the train. The masked outlaws then ordered the crew to go with them to the express car, where they tried to get the messenger to open the door. Charles C. Haswell refused, and he punctuated that with some blasts from a sawed-off shotgun. The bandits responded in kind, shooting through the closed door. During the firefight, the fireman was fatally wounded. But the messenger never did open the door.

The frustrated bandits finally gave up and left.

Southern Pacific Detective Will Smith believed that the Daltons were involved—even though they lacked major criminal records at the time. He went after them, but Bob and Emmett Dalton had already headed back to Oklahoma/Kansas. Bill and Grat Dalton both faced juries; the former, an upstanding California citizen, was acquitted while the latter was convicted (on pretty flimsy evidence). Grat escaped before getting to prison and rejoined Bob and Emmett—the Daltons always denied any involvement in the attempted holdup and claimed that the false charges drove them to a life of crime.

Surprisingly, Express Messenger Haswell—who drove the gang off—was tried as an accomplice, but he was found not guilty.

Nevada

“Gentleman” Jack Davis had the wrong nickname. He was a professional hardcase who specialized in robbing stagecoaches. On November 5, 1870, he turned his attention to trains—the first train stick-up west of the Mississippi.

On that night, he led five others aboard the Central Pacific train at Verdi, Nevada, just west of Reno near the California border. They stopped the locomotive a few miles away, forcing the crew to uncouple the engine and express car from the rest of the train. Then the outlaws made their way to the express safes.

Somebody in the crew had experience in that area, for they picked the locks and quickly got to the cash—about $41,000 in gold coins. The outlaws then lit out, but they somehow overlooked thousands of dollars more in silver, gold bars and bank notes.

Several of the bad guys were eager to live the high life, and their big spending habits caught the attention of Wells Fargo detectives. They questioned one of the suspects and he spilled everything, including the names of his confederates. They were all arrested—including the mastermind, a former Sunday school teacher named John Chapman who was a novice in the art of crime. Chapman just planned things; he was not at the robbery.

Almost all of the loot was recovered, and all six bandits did long stretches in prison.

New Mexico

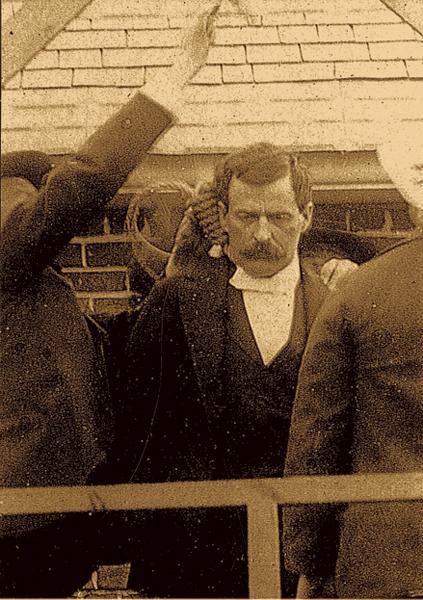

Tom Ketchum was crazy. Unpredictable, violent, reckless, self-destructive. Other outlaws knew it; many, including Butch Cassidy, refused to ride with him.

So Tom decided to go it alone on August 16, 1899. His plan was to hold up the southbound Colorado and Southern train near Folsom, New Mexico, It was a good plan; the train slowed to a crawl at a switchback, and a man could literally walk up and board it.

That’s why the train had been robbed several times at that place, including just a month before by Tom’s brother Sam. As a result, the crew was going armed.

It was around 8 p.m. when Tom stepped on the train. He threw down on the crew, cursing, threatening and actually shooting the express messenger in the jaw. Conductor Frank Harrington got angry—and got a shotgun. And he put a load of buckshot in Tom’s right arm. Tom fell away, and the train continued on.

The next morning, the northbound train passed the site and found Tom, near death from blood loss. But he was still crazy; he pulled a gun on the men who came to rescue/arrest him. He didn’t have the strength to pull the trigger.

Tom lost his right arm, but he would lose much more. He was convicted of train robbery, a capital offense in New Mexico, and sentenced to hang. The authorities didn’t know how to do it, and the drop tore off Tom’s head.

Oh, and that nickname of “Black Jack?” Folks at the time confused him with another outlaw who went by that moniker and began calling him that. Yet his crew never called Tom “Black Jack.”

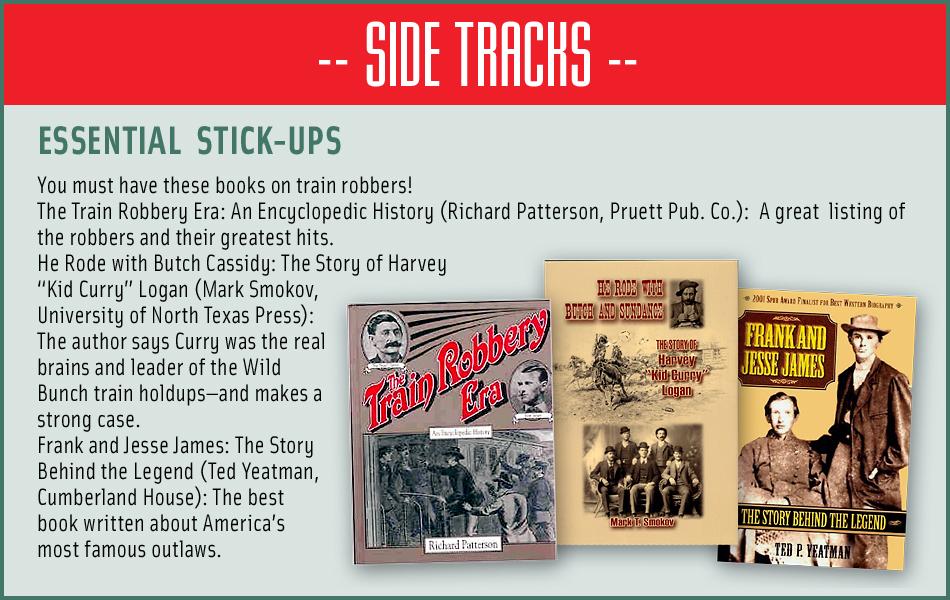

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Mark Boardman –

– Courtesy Arkansas & Missouri Railroad/Mark Boardman –

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin Collection –

– Courtesy True West Archives/Library of Congress –

– Courtesy Loren Brown, Iowa Railroad Historical Society/Twentieth Century-Fox –

– Courtesy Cumbres and Toltec Railroad –

– Courtesy Durango CVB –

– Courtesy Bob Crum, Fillmore, CA –

– Courtesy True West Archives –

– True West Archives –

– Courtesy True West Archives –

– Courtesy Hilary Mertcher –

— Courtesy Texas State Railroad/Warner Bros. –

– Courtesy Nevada Tourism –