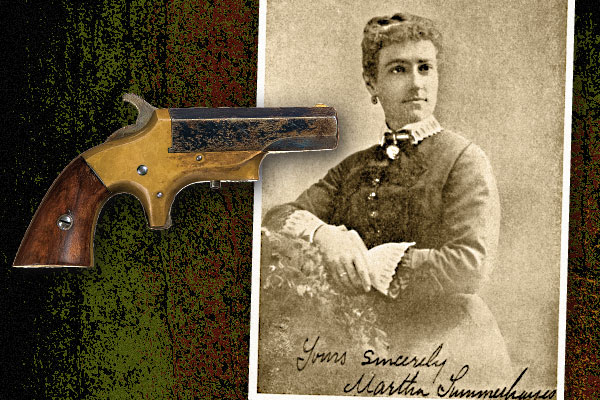

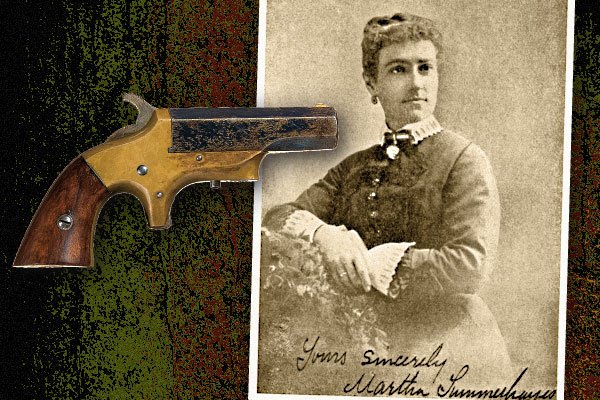

In 1875, when U.S. Army wife Martha Summerhayes’s Army ambulance was being escorted through Arizona Territory, from Camp Apache to Camp Ehrenberg (and ultimately Camp McDowell), she recalled, “I wore a small derringer, with a narrow belt filled with cartridges.

In 1875, when U.S. Army wife Martha Summerhayes’s Army ambulance was being escorted through Arizona Territory, from Camp Apache to Camp Ehrenberg (and ultimately Camp McDowell), she recalled, “I wore a small derringer, with a narrow belt filled with cartridges.

An incongruous sight…it must have been. A young mother, pale and thin, a child of scarce three months in her arms, and a pistol belt around her waist!”

While the exact type of derringer she carried remains unknown, her comment speaks of the felt need to carry some sort of firearm in the untamed West. Most enduring among these small pistols were the single-shot, metallic-cased cartridge arms of calibers larger than the .22 Rimfire.

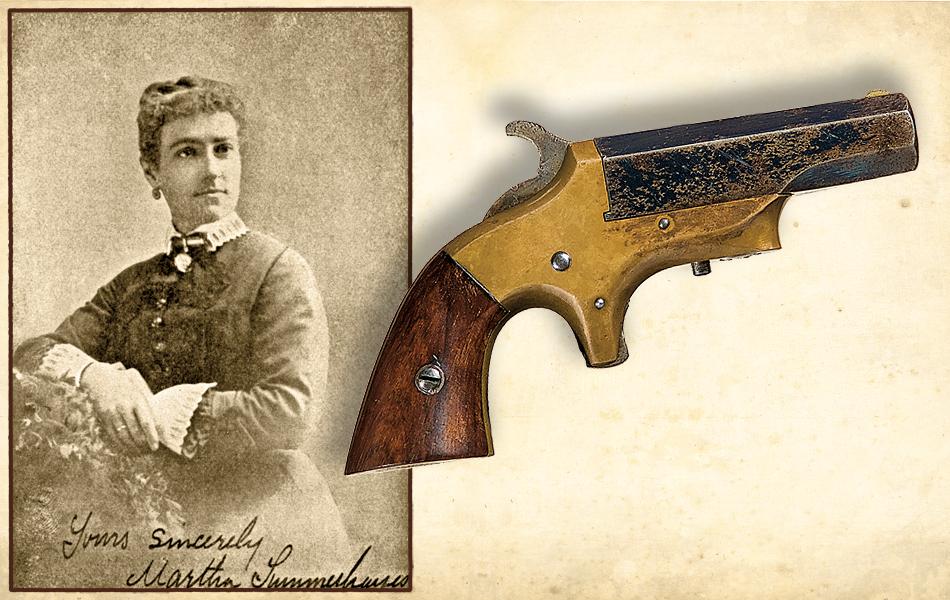

A favorite chambering of such derringers, the .41 Short Rimfire round with its 130-grain lead bullet, was the round used in a pocket-type handgun with the romantic sounding name of “Southerner” stamped on top of its barrel. This palm-sized one-shooter was a popular choice for both law-abiding citizens and those who lived in the shady side of society. The rakish name likely gave it special significance to those hailing from Dixie, despite the pistol’s manufacture in the north.

Charles H. Ballard, best known for his military and sporting rifles, designed the Southerner, which was patented on April 9, 1867. The Merrimack Arms & Manufacturing Co. of Newburyport, Massachusetts, produced about 6,500 Southerners between 1867 and 1869. Then Brown Manufacturing Co., also of Newburyport, took over Merrimack. The Southerner’s design remained the same, while the barrel stamping was changed to reflect the new ownership that produced another estimated 10,000 pistols up until 1873.

Depressing a button underneath the frame pivots the Southerner’s octagon barrel sideways to load, and it is unloaded via a breech-mounted “automatic” extractor. This spur-triggered derringer measured a mere five inches overall and had a blued iron, 2½-inch barrel, although a few were nickel- or silver-plated. Frames were generally silver-plated brass, although some brass frames were left unplated. An estimated 30 percent of Southerners had iron frames. Grips were rosewood or walnut, with a small number turned out with ivory or pearl stocks—generally found on the scarce plated or engraved models.

Most Southerners have square butts, but Brown did produce a limited number with rounded grips (referred to by collectors as “bag handled”) and either 2½-inch or four-inch barrels. Sparking the collector’s interest are the few seconds sold by the manufacturer; these were stamped “Imperfect” on their frames.

Although a derringer like the Southerner could be a handy tool at extremely close range, the .41 Rimfire’s 13-grain blackpowder charge greatly diminished its power beyond a few yards. Nonetheless, the number of specimens found that show significant wear prove these easy to use, small and lightweight cartridge derringers were often carried.

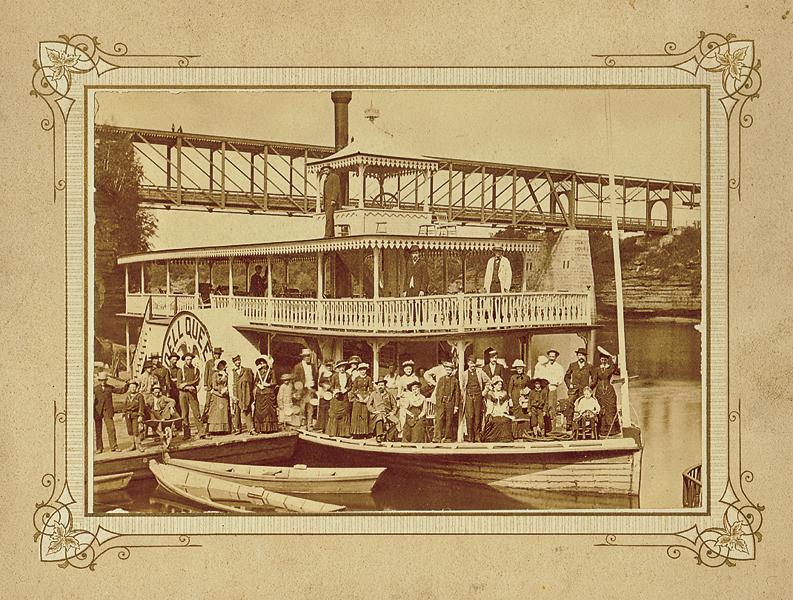

Today, the Southerner is little more than a colorful reminder of the days of smoke-filled saloons and churning riverboats, soiled doves and sporting gents, and everyday pioneers who made their way through the wild West’s precarious territory.

Phil Spangenberger has written for Guns & Ammo, appears on the History Channel and other documentary networks, produces Wild West shows, is a Hollywood gun coach and character actor, and is True West’s Firearms Editor.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Rock Island Auction Company –

– Summerhayes photo true west archives/ Firearm photo Courtesy Rock Island Auction Company –

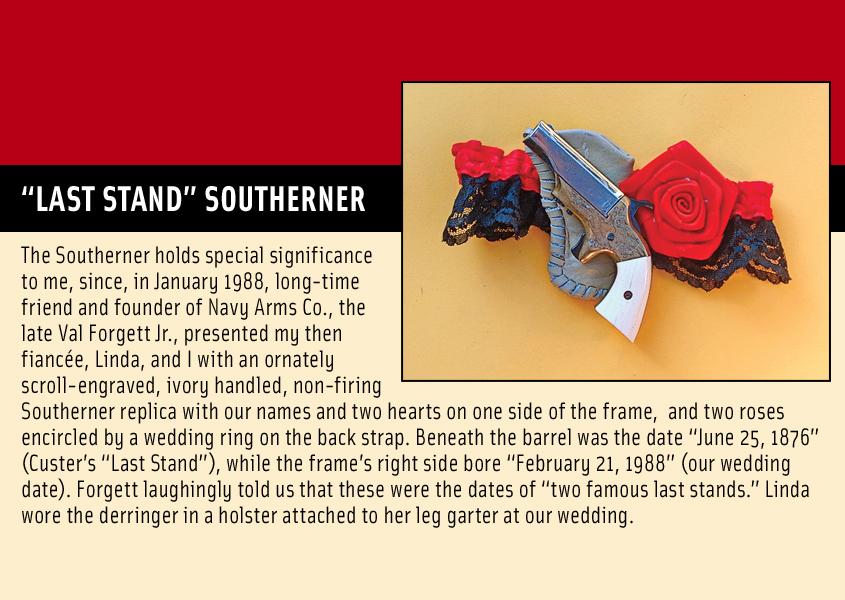

– Courtesy Phil Spangenberger collection –