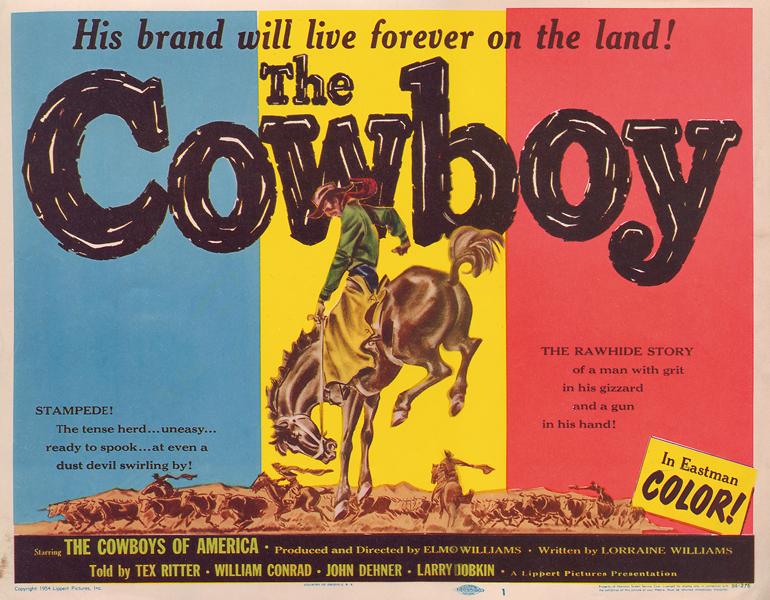

Deming, New Mexico, recently rounded up its cowboys to celebrate the rediscovery of a classic feature-length color documentary, The Cowboy, produced and directed by Elmo Williams, famed High Noon film editor.

Deming, New Mexico, recently rounded up its cowboys to celebrate the rediscovery of a classic feature-length color documentary, The Cowboy, produced and directed by Elmo Williams, famed High Noon film editor.

This powerful documentary depicts a lifestyle that was rapidly vanishing in the West by the mid-20th century. Williams filmed old-timers recalling the past and cowboys rounding up cattle, breaking wild mustangs and square dancing with the ladies, revealing a way of life that dates back to the cattle drives in the 1800s.

In 1952, Elmo Williams arrived in New Mexico’s high desert to film The Tall Texan and soon afterward, The Cowboy for Lippert Pictures. Taking a chance on this Oscar-winning film editor, studio head Robert L. Lippert had hired Williams for his directorial debut. “He was always looking for new talent that worked cheap,” the 93-year-old Williams recalls.

Williams decided to head to Deming to make The Tall Texan because his brother, “Skeeter,” co-owned a meat packing plant there. In the 1950s, Deming was a small ranching community, which had a promising beginning in 1882 when the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad connected with the Southern Pacific. This gave birth to a brawling railroad town considered to be so lawless that outlaws rounded up in Arizona were given one-way tickets to Deming.

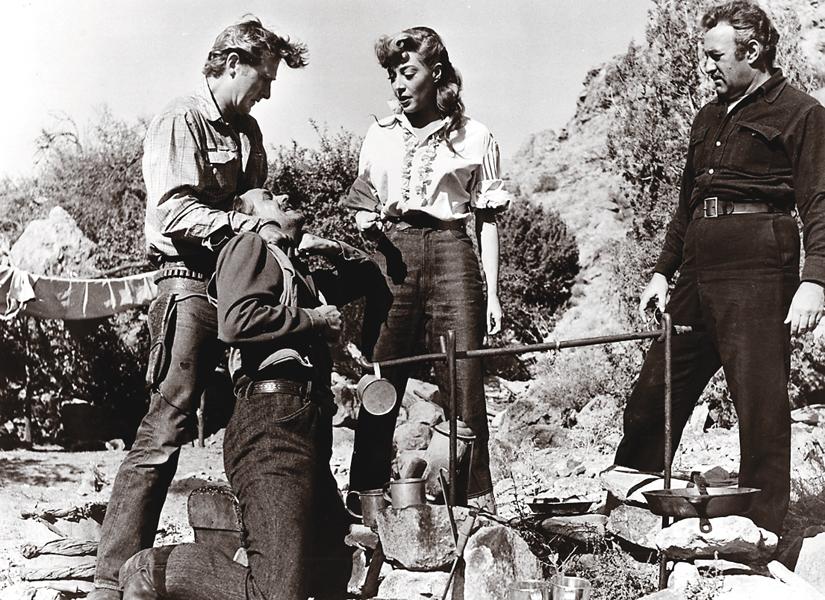

Born and raised in New Mexico, Williams crafted a story about a group traveling through the high desert and discovering gold on Indian burial grounds. Lippert liked the concept and hired a screenwriter. Williams brought in a solid cast, which included Lloyd Bridges, Lee J. Cobb and Marie Windsor. He also gave them his percentage of the film. “They worked cheap because this was during the red scare in the ’50s and they were on the boycott list,” he explains.

The actors read the script on the plane and hated it. They staged a revolt, saying they were going back to Hollywood unless they got a better writer. Williams hired Elizabeth Reinhardt. She wrote dialogue for the next day’s scenes while the cast and crew filmed in the high desert. The crew included several Deming cowboys as wranglers and extras—but these men weren’t Hollywood actors, they were the real thing.

When the Teamster’s Union found out about these cowboys, though, it sent a representative from Chicago. His small airplane buzzed the set and landed in a dry lake bed, covering the actors and crew with dust and dirt. The union rep and Williams argued back and forth, but Williams gave way and hired union crew to complete the picture.

During the eight days of filming The Tall Texan, the cast stayed at a guest ranch near Deming called the Spanish Stirrup. Edgar May owned the place and provided the horses used during the filming. His son Ross, only 21 years old at the time, was the film’s head wrangler. Once the Hollywood cowboys arrived, Edgar didn’t want them riding his working stock and ruining his horses. After a good deal of persuasion by Williams, he finally relented and let those Hollywood boys ride after all.

This inexpensive Western was made for only $102,000 and launched Williams’ career as a director. It was a successful film for Lippert Pictures, which enticed audiences with its colorful poster, exclaiming: “Lure of Danger! Love of adventure! Lust for Gold!”

Capturing a Vanishing Breed of Men

Williams knew he had to return to New Mexico to film a documentary on the lives and times of this vanishing breed of men. He talked Lippert into loaning him $53,000 to make The Cowboy. Unlike The Tall Texan, Williams was able to film this documentary in color because Kodak was experimenting with a different film stock in the 1950s and gave Williams a new type of negative to try out. “I was their guinea pig,” says Williams, laughing while he recalls his later struggle to make color prints with this untried negative stock.

He persuaded his wife Lorraine to write the screenplay and two songs. A neighbor wrote the third song, which, in the end, proved to be the most expensive item in the budget due to music rights.

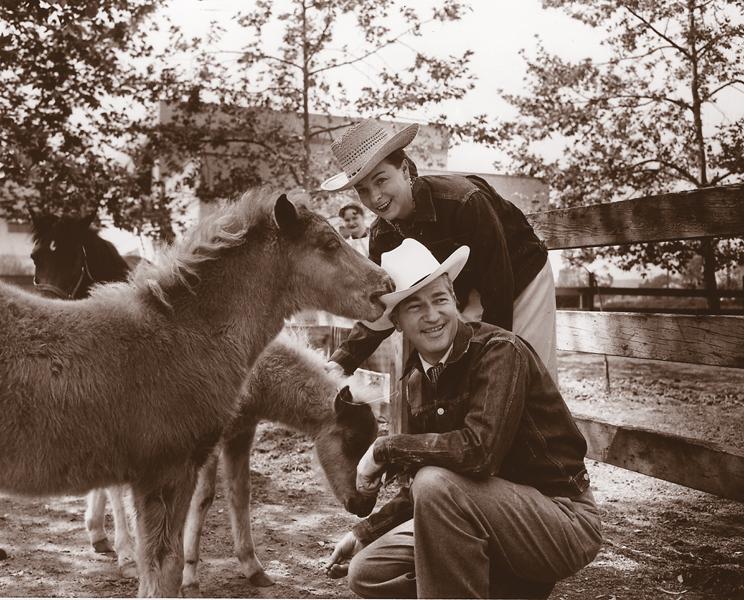

Lorraine protested that she didn’t know anything about the West, Williams says. But she read a lot of books and quickly picked up the cadence of the cowboys’ speech. Not only did she write a good screenplay, but she also accompanied him while filming on and off during a three-month stretch. He was the director, the cinematographer and the film editor. They slept under the stars with the cowboys, rode the same trails and shared their hot black coffee, tough beef and beans.

Williams rehired Ross, while Skeeter recommended several other cowboys, including Robert and L.B. “Beau” Johnson, who were delighted to work for the filmmakers because central New Mexico was suffering through a five-year drought. The cowboys worked for “beer and beans,” Ross says, but Williams had to pay for the use of the horses. L.B. recalls being paid $18 a day, at a time when ranch hands only made $3.50 a day. Williams would later dedicate his film to these hardworking cowboys who ranged in age from their teens into their 80s: “Bob, Beau, Manny and Ross and all the others whose hearts are as big as the country they ride!”

Williams wanted to film cowboys driving long-horned cattle known as Corrientes, but they had almost vanished from the American landscape. Later on, this breed was brought back into the states and is now often used in rodeos for roping stock. At the time of the film, though, the Yaqui Indians herded these cattle in the mountains of northern Mexico in the state of Sonora. Williams headed down to Mexico to make a deal with Octavio Elias, a local rancher and the Indian chief. At first, the Yaquis thought Williams was a cattle buyer and couldn’t believe that he only wanted to film their stock. The filmmaker had to drink endless cups of coffee with the chief until he agreed to let him use the cattle. “If he hadn’t liked me, not all the money in the world would have gotten me those cattle,” Williams says. “But since I didn’t have any money, it was all right.”

While filming the cattle drive which begins The Cowboy, the Williams slept on army cots while the cowboys slept on the ground. The Indians kept the fire going all night and during the day, and used their machetes to clear trail. These Indians were, “incredible people,” Williams says. At the end of the cattle drive, he gave them knives, photographs and a little money.

Afterwards, the couple returned to New Mexico, and Williams continued to film using cattle that were mostly Hereford and Angus stock. Borrowing a drive-in theater projection booth, Williams would edit at night. He and Lorraine filled the back of their battered Plymouth station wagon with ice chests to keep the film stock cool, while they slept underneath their car.

When a scene called for a desert whirlwind, Ross sent the Williams to a dry lake bed and told them to “be patient.” They waited several days in the hot, dusty area until, at last, the wind rose and Williams could film. He also filmed a coyote attacking a cow with her calf, which would not be allowed today because the coyote was tethered and the cow was not allowed to escape. Many scenes were also filmed near Monticello, which is nearly a ghost town, and Truth or Consequences, fondly known as “T or C” by the locals.

The Williams took good care of their cowboys. Several times, the couple rented a dance hall in Deming and threw parties for their amateur cast. The 71-year-old L.B. Johnson recalls feeling like he and his companions were “living high on the hog” during those few months.

Brought Back to Light

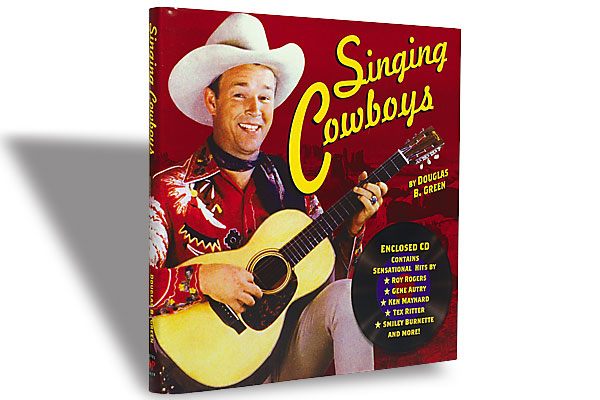

After returning to Hollywood, Williams hired several narrators, including Tex Ritter who also sang “Dodge City Trail” in the film. Williams never saw any money from the project because he was in England working on another picture when Lippert released it without his knowledge. But Williams says, “I paid my dues.” At 93, he is still as proud of this documentary as of any film he has directed or produced throughout his long Hollywood career.

This 1953 documentary has not been seen for decades and was thought lost, but Kit Parker, a veteran distributor of classic films, found it after purchasing the Robert L. Lippert film library in 2004. Parker discovered that Lippert’s films had been improperly stored for many decades in vaults that lacked air conditioning. Some negatives deteriorated almost beyond repair.

The Cowboy was in such precarious condition that Parker sent it to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences to be examined. The Academy advised Parker that the color negative would cost over $100,000 to restore.

With that news, Parker went back to the library, where he found a negative in good condition that was used for TV in the 1960s. But it was in black and white. With a stroke of luck, he located an excellent 16mm color print made directly from the color negative before decomposition had begun. This negative enabled him to painstakingly restore the highly acclaimed documentary with its original color photography that stunningly reflects this vanishing lifestyle in the Old West.

Last year, New Mexico’s Luna County Film Commission showed both films to celebrate its Western heritage and “Hollywood” connection. Part of the festivities included a grand reunion and interviews with the original cast members and participants in The Cowboy. Their colorful reminiscences make up a special commentary on the DVD, which will be released by VCI Entertainment this January.

Photo Gallery

– All images courtesy Kit Parker Films –