How many times have you looked at an antique photo and thought, “If this old photo could only talk?” Well, they do, in a way.

As a collector of antique photographs of Old West subjects, and through my studies of thousands of vintage photographs, I’ve learned much about the guns and gear of yesteryear. By the medium of photo-graphy, primitive as it was in those early years, these colorful folks were leaving a firsthand record of who they were, how they looked and, to a small degree, something about their personality.

While the study of antique arms is enjoyable, many firearms enthusiasts also share my curiosity about what life may have been like in the era of these arms being studied. In the photos I have collected, I have realized many of the pistol-packing cowboys and miners, the tomahawk-wielding Indians and the high-booted frontiersmen in these photos were not “Hollywood” costumed actors, so dressed for a theatrical role. These Westerners were the genuine articles, outfitted in their everyday attire and showing off their “hardware.” In cases where the subjects were obviously sporting dressier-than-usual clothes for the sake of the then-new camera, I know that the clothing and shooting irons were still authentic to the era, even if the subject might not have personally owned them.

A Record of Frontier Life

Through looking at old photos, certain myths about the Old West and its inhabitants have been proven true or false. I’ve learned to “never say never,” when it comes to stating a fact about when, where, how or by whom a certain firearm or piece of gear might have been used. For example, I’ve found photographic evidence of holsters being used long before their generally accepted time of usage. The photos, which are well documented as to the date of their exposure, showed troopers using this gear, when for generations collectors had assumed otherwise.

At the time of our Westward movement and the frontier years preceding Western statehood, photography was still in its infancy. Photographic equipment was big, bulky and tedious to handle. Exposures were slow, and developing the exposed plates or negatives demanded that a complete field laboratory be set up. Because of these factors, extra gear was out of the question. The same can be said for the subjects of these photographs; they did not lug photo props around in the wild, rugged terrain of the frontier. Therefore the most believable images of how people dressed and looked, and what arms they favored in the mid- to late-19th century, can often be found in those views taken in the field or candid shots, such as street scenes and store fronts.

As the 20th century approached, advancements in photography enabled amateur shutterbugs to take the smaller, less cumbersome equipment, like the Kodak Brownie box cameras, into the backcountry to record what they saw, thus producing an abundance of outdoor views from around the turn of the 20th century.

Back in their studios, many frontier photographers kept props, such as firearms, army uniforms, buckskin coats, chaps, hats and other colorful bits of Western gear, to provide to their subjects. For example, early Montana photographer L.A. Huffman kept a Sharps buffalo rifle in his studio for such purposes. This same rifle appears in several of his photos—sometimes cradled in the arms of an Indian, other times leaning against an Indian burial scaffold in the middle of an open prairie. Remember, these men were more than just photographers recording what was in front of their camera’s lenses. They were also artists, and some of them were very good! Huffman’s photos have stood the test of time and are, as an art form, as appealing today as ever.

How to Date a Photograph

I’ve spent many enjoyable hours speculating about the pioneers in these photographs and learning on the ways of our forebearers from them. For example, an early carte de visite photograph, which I purchased for the outrageous price of $6 in the late 1960s, shows a Western gent wearing a bib-front shirt and scarf tie, trousers tucked into high-topped boots (no spurs), a rakish broad-brimmed hat, turned up in front, and a Model 1860 Spencer seven-shot repeating carbine in his hand.

I bought this image primarily to display along with a Spencer carbine I owned in my collection. Yet without uttering a sound, this man was telling me about himself. I surmised that, possibly as a young fellow (he looked to be somewhere between the ages of 18-26), he was seeking his fortune in some profession, particularly one that required he be armed. He likely purchased the Spencer cheaply, as it was being sold as Civil War surplus. His attire suggests to me that he worked outdoors, while his natty look gives off the impression that he was somewhat fashionable in his dress and wanted to impress someone that he was indeed a Westerner, living an adventurous life.

As with so many antique photos, the back of this carte de visite carries the fancily printed name of the photographic studio’s location. This one is marked Durango, Colorado. The clothing style and the firearm are the only clues to the era of the photo, so I suspect the image to date from around the founding of the town in 1881. Of course, where no name or any form of definite identification can be found, such deductions are purely speculative. Nonetheless, my “guesstimate” as to the details of this frontiersman is based on what is seen in the photo.

Weeding Out the “Fakes”

In collecting antique photos—as with all other collectibles—one must be aware of forgeries. With today’s interest in living history, many hobbyists dress up for photo portraits in their authentic garb, with guns and other accessories. Because most of these pictures are taken for private enjoyment, modern photographic techniques are usually used. Occasionally though, an above-average quality, or even a modern-exposed tintype photo, will get out into the collector market to be passed on to an unwary or unscrupulous seller.

Modern “faked” photos are just one pitfall awaiting the antique photo collector. Just as with modern photos, antique images cannot be accepted at face value. Many of these were “faked” at the time they were taken, through the use of props, retouching, trick photography or costumed models. This may have been done to simulate an event or create a saleable image in the 19th century. Or perhaps photographers did

it for the sheer enjoyment of trick photography, just as today’s photographers might employ the latest methods of photographic technology to create a desired image.

Before purchasing any photo, study it closely. I once received a gift of a trio of stereoviews of South Africa’s 1899-1902 Boer War. At first glance they appeared to be authentic shots of a Boer artillery crew in action. After close inspection, they turned out to be posed shots—complete with poorly costumed models using American web .45-70 bandoliers and Civil War-vintage Springfield muzzle-loading rifle/muskets—hardly the choice of the Mauser rifle-armed and firearms savvy Dutch Boers at the turn of the 20th century! One of the images even revealed a cannoneer with a “clip-on” white beard with his dark hair. The photos also showed evidence of an American-style farmhouse that had been opaqued over in order to remove it from the so-called “South African bushveld.” Entertaining, but hardly authentic.

Many of the antique photos the collector will encounter of 19th-century people may be colorful at first glance, but a closer inspection may reveal subjects who were simply dressing up for the camera, possibly to impress their Eastern kin. One big telltale clue is someone dressed in cowboy attire, but also wearing city duds like lace-up shoes, starched collars and ties, and other items of clothing an honest-to-goodness cowpoke would not normally wear. While a photo like this may not be representative of a real working cowboy, the image still offers insight to the clothing, firearms and other tools of the period. At the same time, such an image should be acquired at a considerably reduced fare.

Highly Collectible Gun Shots

Regardless of the particular subject of interest, or type of photo, antique photography provides a fascinating and informative look at our past. Photographic images, especially those clearly displaying firearms, have escalated in price in recent years. Original images of famous people are generally among the most valuable—particularly if they are signed by the subject. Next in popularity with the firearms photo collector are those likenesses that display, in an attractive and clear view, a highly collectible firearm, such as a Colt Peacemaker, or a Sharps or Winchester rifle, in full view or prominently brandished in a realistic fashion. While such portrayals can easily run into several hundreds of dollars, the determined photo hunter can still find a treasure amidst a pile of European monuments and portraits of grandparents, babies and second cousins.

When I find such a prize, I get the same feeling I used to get years ago when I would find an old Colt revolver at a bargain price. I rush home, break out the trusty magnifying glass and start “listening” to what the Westerner in the image is telling me. I know if I pay attention to what is shown in the photograph, I’ll learn more about him, his firearms and his life. It’s like traveling back in time, and how many among us have dreamed of such a trip?

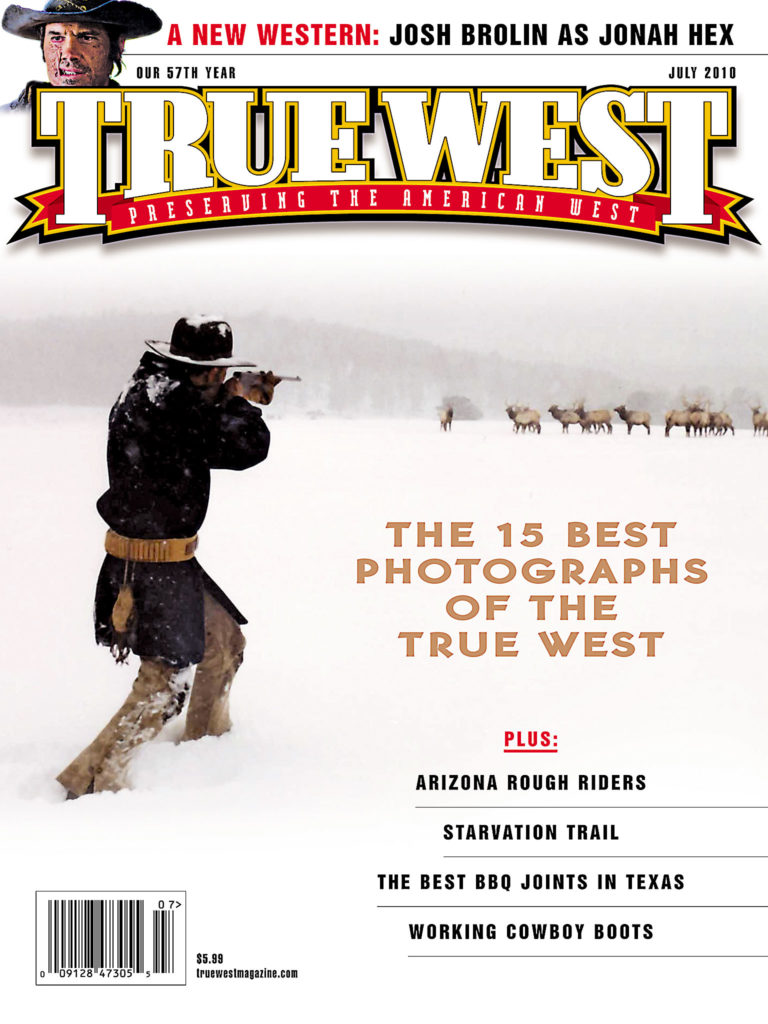

Phil Spangenberger writes for Guns & Ammo magazine, appears on the History Channel and other documentary networks, produces Wild West shows, is a Hollywood gun coach and character actor, and is a Field Editor and regular columnist for True West.