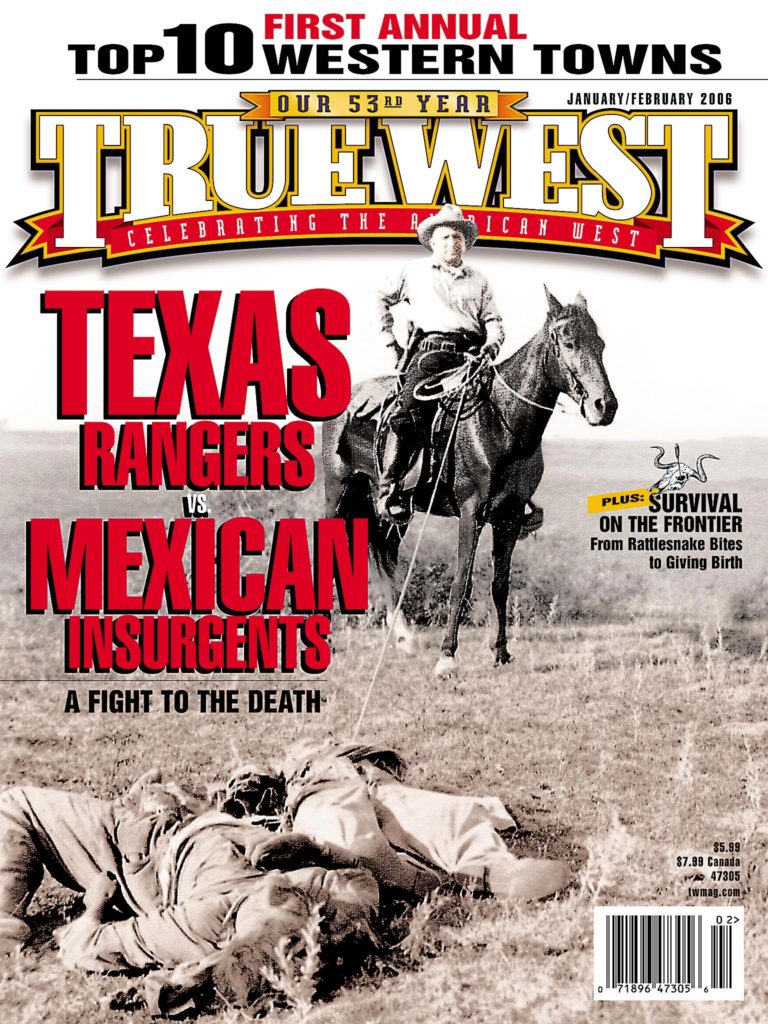

A life-or-death price tag came with settling the Old West: By their wits, their guts and their best guesses, Westerners had to learn to survive.

A life-or-death price tag came with settling the Old West: By their wits, their guts and their best guesses, Westerners had to learn to survive.

If they lived on remote farms or ranches, virtually everything to get through the day was a yoke on their shoulders. Even if they lived in the rough and tumble towns that dotted the landscape, “services” were skimpy. Mining camps assured only one commodity: a saloon.

Imagine the horror of Barbara Jones, raising a family of 10 sons in New Mexico Territory in the 1870s, the day her Sammy nearly tore off his eyelid. The nearest doctor was 150 miles away. She held the boy down on the kitchen table and using her sewing kit, sewed his eyelid back on. Because she had to. Sammy Jones ended up with one crooked eyelid, but he kept that eye and lived to be an old man. Thanks to his Ma’am Jones.

Or imagine the stamina of Mountain Man Jedediah Smith, whose scalp was almost torn off in a grizzly bear attack. “You gotta fix me up,” he told his men. One took a big needle and black thread, and started sewing.

Everyday life wasn’t always dramatic in the Old West, but survival meant more than just treating wounds; it also meant keeping food on the table, making medicine for dreaded diseases, keeping the family clean and fighting off voracious critters.

A peek into some survival techniques gives a good idea what everyday life was like in the 1800s.

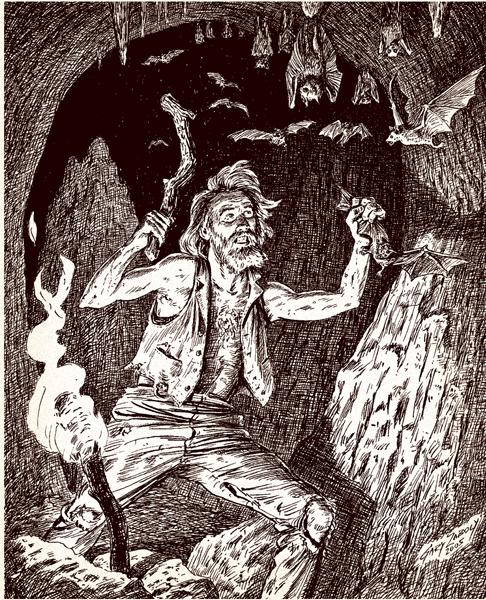

What to eat when stranded in the desert?

Bats. Pioneers knocked them down with a stick from cave walls. The trick was to wait until the vermin crawled off before cleaning the bats. Once skinned, they were roasted over an open fire. The reward was white, tender, delicious meat. Snakes and lizards also made good meals. It was just catching them that was hard. Flower petals were one option that wasn’t likely to run away. But if the flower tasted bitter or the plant had discolored juices, settlers moved on to another plant. Tree bark also worked, especially birch and willow. Bark was roasted over coals to loosen the fibers, but it was still pretty chewy.

Thirsty?

Westerners retrieved water from the barrel-head cactus by squeezing the pulp. If they couldn’t find water, their next best bet was a button. By holding a button to their tongues, it stimulated saliva flow and kept the mouth moist.

Protection Against the Desert Sun

Pioneers made frameworks of yucca stalks or whatever else was at hand. The tops and sides were covered with a brush mat. When available, tarp or cloth material was used.

Keeping Rocks Out of Your Footwear

On the dusty trails out West, rocks were bound to get into one’s walking gear. Travelers were advised to wrap cloth around their ankles and over their shoes. That kept most of the rocks (and sand) out.

Home Remedies

Pioneer women brought some of their home remedy knowledge with them from back East; others they learned from Native women. For Malaria, often called “ague,” some believed a fresh-killed chicken would help—if its flesh was placed against the bare feet while the patient swallowed a cobweb rolled into a ball. To trigger sweating, they made snakeroot tea; for rheumatism, they used poke root; and to stanch bleeding, they covered the wound with cobwebs.

They believed turpentine would heal almost any sore; that snuff helped take the sting out of red-ant bite; or that a nail in the foot demanded you wrap the limb in a rag soaked in coal oil to prevent lockjaw.

Those Damn Snakes

It’s impossible to read any diary of the Old West without noticing the constant references to the numerous and deadly rattlesnakes—one states they “ruined every picnic, soured every outing.” Antidotes for a snakebite included gunpowder and vinegar; brandy and salt; alum; a drink made from the bark of the black ash tree; tobacco juice; and applying to the bite the fleshy part of the tail of the killed snake to draw out the poison.

A Gunpowder Cancer Cure

Mrs. Edith Wheeler of Texas reported that she’d cured skin cancer on Uncle Rufe using her mother’s favorite wart ointment of crushed leaves of a weed called sheep sorrel. “I didn’t know how it would work on cancer, but I figured it wouldn’t kill Uncle Rufe…. To make the medicine strong, I mixed in gunpowder … and smeared that cancer with fresh applications every day. Uncle Rufe swore it burned ‘worse than hell’…. But [after] five days that cancer slid off his face like a dried scab.”

Gunshot Wounds were Bad News

Gunshot wounds were the most startling of calamities. Besides childbirth, this was the time when families most wanted a doctor. Sometimes families were forced to extract the shell themselves, but often they focused on stopping the bleeding and praying infection didn’t set in. And it’s obvious that even trained doctors were guessing. Most telling was the death in 1901 of a 58-year-old man shot twice in the abdomen at close range with a .32 caliber pistol. He was lucky enough to get almost instant medical attention. After surgeons removed the bullets, they reported he was recovering nicely. He died eight days later. He was William McKinley, the 25th president of the United States.

Night Terror

As Joanna L. Stratton describes it in her Pioneer Women: Voices from the Kansas Frontier: “Nightfall, blanketing the prairie in a dense, boundless blackness, brought an even keener sense of solitude to the pioneer home … it was during the black nights that the howl of the coyote and the wolf spread terror throughout every frontier homestead. Often roaming the plains in packs, these rapacious animals would attack without provocation or mercy.” Families kept guns and clubs close at hand when the animals tried to break into their homes.

Fire!!!

Prairie fires, which could wipe out everything in a matter of hours, were a constant fear for early settlers. To protect their homes, many homesteaders plowed a wide strip of ground, which was called a fire guard. But fire fueled by the strong prairie winds sometimes jumped these furrows. So a frontier family had to always be on guard and ready to fight a fire, using buckets of water, pails of dirt, wet blankets and grain sacks.

In a Pinch

Homesteaders sometimes made a “coffee” from parched corn and sorghum sweetening. They made vinegar from melon juice and tapped box elder trees for sap to make syrup.

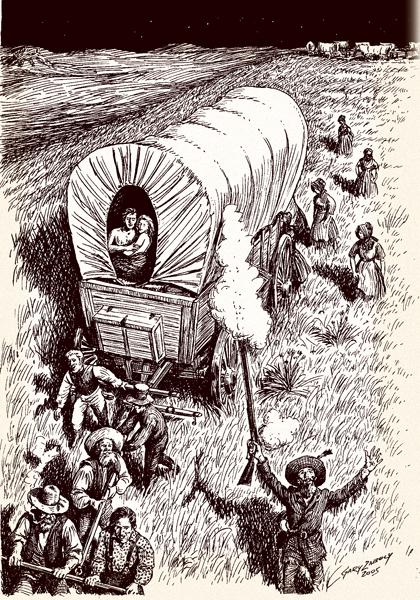

Let Them Eat Butter

Wagon trains were jam-packed with the necessities of a new life, and there certainly wasn’t any room for a butter churn. But imaginative women soon realized that if you hung the morning’s milk in a pail under the wagon, the constant motion would give you butter by the time you camped for the night.

Just the Staples, Please

As Lillian Schlissel reports in Women’s Diaries of the Westward Journey, the 1845 “Emigrant’s Guide to Oregon and California” recommended each emigrant supply himself with 200 pounds of flour, 150 pounds of bacon, 10 pounds of coffee, 20 pounds

of sugar and 10 pounds of salt. Along with that, recommended staples were chipped beef, rice, tea, dried beans, dried fruit, baking soda (called saleratus), vinegar, pickles, mustard and tallow. One of the travelers later wrote that no one should take this trip without medicine, including “a quart of castor oil, a quart of the best rum, and a large vial of peppermint essence.”

Hurrah for the Chivaree

A wagon train provided almost no privacy—a point that would become particularly important to couples that tied the knot during the trip West. One response was the chivaree. One diary noted how happily the rest of the company chivareed a young couple: “The newly married couple occupied a wagon for sleeping apartments. The first notice they had of any disturbance was when most of the men and women in the company took hold of the wagon, the men at the tongue pulling, the women at the back pushing, and ran the wagon a half mile out on the prairie. Then the fun began. Such banging of cans, shooting of guns, etc. and every noice [sic] conceivable was resorted to. The disturbance was kept up until midnight when the group dispersed, leaving the happy couple out on the prairie to rest undisturbed until morning when they came walking into camp amid cheers and congratulations.”

How to Cure an Earache in 1869

Almost “instant relief” was promised with this cure: Take a small piece of cotton wool, make a depression in the center, fill it with as much ground pepper as will rest on a five-cent piece, gather it into a ball, tie it up, dip it into sweet oil and insert into ear. Cover the ear with cotton wool and a bandage, or cap to keep it in place.

How to Clean Hair

Take one ounce of borax and half an ounce of fine camphor powder. Dissolve in one quart of boiling water. When cool, the solution will be fit for use in washing hair. “This wash effectually cleanses, beautifies and strengthens the hair, preserves the color and prevents it from falling out,” reported The Miner newspaper in Arizona Territory in 1868.

Secrets of a Ranch Cook

According to a story written by an “old-time sour-dough” ranch cook for the Federal Writer’s Project during the Depression, the usual grub on the range during roundups was like this:

“We had meat at every meal. A fat heifer was killed at sundown and hung outside to cool. Before sun up I cut off enough for the day’s needs, wrapped the rest in a meat tarp, and put it in the shade. After sundown I removed the tarp and hung the meat out again. It is surprising how well beef will keep when handled in this manner. Frijole beans, potatoes and hot biscuits were served at every meal. Lick [syrup] took the place of butter. Dried fruit cooked with plenty of sugar was the usual dessert. Canned milk was bought in town. In those days coffee was called ‘Jamoka.’ Tea was never used. The coffeepot was always busy when the punchers were at the ranch.”

Respecting the Dead

In Spanish culture, strict tradition governed burials. Grace Martin, who was born in Spain and immigrated to Arizona, explained: “Deceased men were dressed with clothing representing saints, such as Saint Joseph, St. Francis, St. Anthony; married women were dressed in black. The men bore these bodies to the burial. Young women and boys were dressed in white for burial, while little girls were adorned in blue with little silver and gold stars cut from paper. Little boys carried the bodies of little boys to the cemetery, while little girls carried the bodies of little girls. The women in mourning did not go to the cemetery nor the funeral service.”

Giving Birth

In the Papago Tribe, a mother-to-be was segregated in a brush hut built for the purpose. She and her newborn remained there for a full month under a strict regime, including special dishes only she could touch. The father, too, was subject to strict discipline. Before the birth, he could neither go to war nor hunt, for this might take strength from the child. At the end of the month, the family sponsored a ceremony strikingly similar to a baptism, and the new child was welcomed into the tribe.

What’s in a Name?

While Arizona had Tombstone, and Colorado a town named Monument, some names seemed off limits. As The Tombstone Epitaph reported in 1887, “No state or territory shows up with a town called Shroud or Coffin or Corpse. Verily, the possibilities of ghastly nomenclature are not exhausted.”

The Drudge of Laundry Day

One pioneer woman, with her unusual spellings, made this list of 11 items to guide her work on wash day, as reported by Sandra L. Myres in Westering Women and the Frontier Experience, 1800-1915:

1. bild fire in back yard to het kettle of rain water.

2. set tubs so smoke won’t blow in eyes if wind is peart.

3. shave 1 hole cake lie sope in bilin water.

4. sort things. make 3 piles. 1 pile white, 1 pile cullord, 1 pile work britches and rags.

5. stur flour in cold water to smooth then thin down with bilin water [to make starch].

6. rub dirty spots on board. scrub hard. then bile. rub cullord but don’t bile just rench and starch.

7. take white things out of keetle with broom stick handel then rench, blew and starch.

8. pore rench water in flower bed.

9. scrub porch with hot sopy water.

10. turn tubs upside down.

11. go put on cleen dress, smooth hair with side combs, brew cup of tee, set and rest and rock a spell and count blessings.