“The God of the Christians is dead. He was made of rotten wood.”

“The God of the Christians is dead. He was made of rotten wood.”

These words, allegedly uttered in his native language by Tewa holy man Popé, marked the beginning of the Indian renaissance in North America.

For some time, Popé had been telling his fellow Pueblos that the source of their woes was the Spanish: If the Indians drove these bearded interlopers from their homeland, rejected Christianity and returned to their ancestral ways, their life would again be good.

In 1680, the holy man finally united the independent Pueblo communities to his cause. Rebelling against Spanish cruelty, the natives revolted, driving their conquerors out—at least temporarily—and launching a massive change in Indian culture.

Bowing to the “Yoke of Christ”

Decades before Popé’s declaration, Spanish conquistadors, led by Juan de Oñate, had introduced Christianity to the Pueblo Indians of the Rio Grande watershed. In 1598, Oñate, the newly appointed governor and captain-general of New Mexico, led a force of eight Franciscan friars and about 130 soldiers (plus their families and servants—around 400 people, altogether) into the valley of the Rio Grande, home to an estimated 50,000 Indians, who lived in 60 villages or pueblos, as their communities were called.

In 1610, Santa Fe—the city of Holy Faith—became the capital of the New Mexico colony, igniting a land rush of retired Spanish soldiers, who received large land grants for their former service. The soldier/settlers built haciendas on their new rancheros and pressed the Pueblo Indians who had been living there into servitude. Of course, other soldiers were always on hand to see that the Pueblos complied with the wishes of their Spanish masters.

Catholic priests also “taxed” the Pueblos for their labor, requiring them to build churches and tend clerical farms. The friars’ demand for native labor often put the priests at odds with the Spanish settlers, who felt the Indians’ time would be better served working for them, writes historian Geoffrey C. Ward in The West. The Franciscans further angered the Pueblos by ordering them to put aside their traditional religion and instead bow to the “yoke of Christ.” Publicly, the Indians paid lip service to Christianity, while within their kivas—underground rooms used for native ceremonies—they continued to worship their traditional gods.

In addition to planting corn and melons for their Spanish masters, the Pueblos also tended the Spaniards’ enormous herds of cattle, sheep and horses (called “sacred dogs” by some of the Plains Indians because they looked like magical dogs that could carry heavy loads).

The Spanish livestock caught the attention of the Apaches, who had begun moving into the region from the East in the late 16th century. Although the Apaches traded with the Pueblos, they also raided them for plunder, particularly horses and mules. Initially, the Apaches ate most of the animals they captured, but they soon began bartering their surplus to the Kiowas and other neighboring tribes. Before long, Spanish horses and their offspring were being swapped from tribe to tribe through a vast Indian trading network that extended north to the Missouri River and into Canada.

From the West, Navajos, like the Apaches, also raided the New Mexico rancheros for horses. From the Navajos, horses passed through the Utes to the Shoshonis and on to the Nez Perce and other tribes of the Northwest plateau country.

Rather than chase the horse thieves, the Spanish replaced their losses by importing more stock from their rancheros in central Mexico. A typical small Mexican ranch of the period had over 150,000 cattle and 20,000 horses, reports Ethno-historian Alfred W. Crosby in The Columbian Exchange.

Although stolen horses filtered through the Indian trading network, their numbers were too few to alter native life on the Northern Great Plains. For the most part, tribes such as the Blackfeet, Crows and Assiniboines continued to be pedestrian nomads who used dogs as their beasts of burden. But all of that was about to change.

The Great Pueblo Revolt

During the 70 years after the founding of Santa Fe, various Spanish governors, settlers and their priests systematically looted the Pueblo Indians of New Mexico. Not only did the Spanish steal Pueblo land and labor, but they also raided the Apaches for slaves to export to Mexico’s silver mines. In retaliation, the Apaches, who also sold captives to the slavers, stepped up their attacks on the Spanish-controlled Pueblos.

During the 17th century, smallpox, measles, diphtheria and other European diseases also beset the Pueblos. In 1638, one-third of all Pueblos—perhaps as many as 20,000 people—died, most probably from smallpox. Two years later, disease claimed another 10,000. And then in the 1660s, the rains stopped, as the Pueblos’ homeland entered a period of prolonged drought.

Frustrated, small pockets of Pueblos began lashing out at their Spanish masters, who retaliated in 1675 by charging 47 Indian leaders with witchcraft. All were beaten and three were hanged when they refused to submit to Spanish authority. The Spanish would have sold the surviving prisoners into slavery, including Popé, the Tewa holy man, Ward writes, had not a large group of armed Pueblos interceded on their behalf. Rather than risk his outnumbered soldiers (at the time, there were fewer than 3,000 Spanish of all ages in New Mexico) in a lopsided fight, New Mexico Gov. Juan Francisco de Treviño released Popé and the other captives.

On August 10, 1680, the Pueblo Indians revolted en masse, killing 21 of New Mexico’s 33 Franciscan priests and 375 (some reports say as many as 500) Spanish settlers. Terrified, the remaining Spanish barricaded themselves in the Palace of Governors in Santa Fe, while Pueblo warriors laid siege to the building and razed the rest of the town.

For 11 days, the Spanish huddled together inside their adobe fortress before finally fighting their way through the Pueblos and fleeing southeast to the mission at El Paso del Norte. It would be 12 years before the Spanish would regain control, but during the dozen years they were gone, Popé initiated the Plains Indian renaissance.

“Sacred dogs” increase mobility

Having orchestrated the Spanish defeat, Popé appropriated the governors’ palace in Santa Fe for his own. Vowing that the good life would return to their homeland if the Pueblos abandoned all things Spanish, he ordered his followers to embrace their traditional religious ceremonies and renounce Catholicism. He also demanded that the Pueblos destroy the Spanish-introduced fruit orchards and other European crops and that they cast aside their metal hoes—which helped produce more bountiful harvests—in favor of those made from antler and bone. And most significantly for the Indians of the Great Plains, Popé insisted that the Pueblos empty the Spanish rancheros of their vast horse herds.

Almost overnight, what had once been a trickle of stolen horses in the Indian trading network became a floodtide of horseflesh. Native Americans acquired most of their horses “as a result of the Pueblo Indian uprising of 1680,” writes Herman J. Viola in After Columbus: The Smithsonian Chronicle of the North American Indians.

As more and more tribes obtained horses, their mobility increased. The Sioux, who lived in the Minnesota lake country, changed from what Viola describes as a “canoeing people” to some of the “greatest light cavalry history has ever known.” Pressured by their Ojibwa neighbors, the Sioux began a multi-year exodus from their traditional homeland to the Western Plains. Buffalo became their staple, as they increasingly hunted from horseback.

Horses now allowed Plains tribes to travel farther afield and much faster than ever before. Horses also altered native hunting patterns. Instead of killing buffalo at buffalo jumps, Indian warriors could kill them from horseback. Because a buffalo cow’s meat was more tender to eat than a bull’s and a cow’s hide was easier for Indian women to tan, mounted Indians began hunting more selectively, especially when buffalo were plentiful. This changing ratio of cows-to-bulls-killed—especially from 1830-60, during the peak years of the buffalo robe trade—eventually altered the sexual composition of the herds.

Because Indians viewed horses as wealth, they naturally sought to acquire more, both through breeding and by stealing from their neighbors. Horse raids now became an important means for warriors not only to build larger herds but also to acquire status within their tribes. Needing grazing land for their growing number of horses, Indians often drove the buffalo from the prime grasslands, which further stressed the buffalo herds.

The use of horses also altered the traditional trading patterns of tribes such as the Nez Perce. Now when they traveled from their plateau homeland in Eastern Washington and West-central Idaho to the Montana prairie in order to hunt buffalo, they could carry more than just enough supplies to satisfy their subsistence needs. Packing their horses with excess salmon oil, salmon pemmican, camas bread, hemp twine and composite bows (laminated with horns from bighorn sheep), they traded with the Blackfeet, Crows and Assiniboines for catlinite pipes, war bonnets and similar truck. (It was common for tribes to put aside their traditional hostility with their neighbors in order to trade.) Just as free trade raises the living standard of nations worldwide, it did so for all trading-oriented tribes in North America.

Spanish Rule Returns

Although the wide use of horses began a renaissance among the tribes of the Great Plains and Northwestern plateau country, the same was not true for the Pueblos, who had traded off the Spanish stock. They had merely exchanged one despot for another. Popé ordered all churches destroyed and all Christian-sanctioned marriages absolved. Crosses, rosaries and everything else “tainted” with Catholicism were to be smashed or burned, and those Indians who had been baptized were commanded to wash themselves clean.

Decreeing that the Spanish language was never again to be uttered, Popé began wearing elaborate costumes and adorning his head with the horn of a bull. Pueblos who failed to heed the holy man’s dictates were imprisoned or executed.

As the Pueblos seethed under their new taskmaster, many noticed that the rain did not return as he had promised. The traditional crops of corn, squash and beans that Popé had ordered them to plant withered under the boiling sun just as the Spanish crops of peaches, melons and grapes had done before the revolution.

Popé died in 1688, whether from natural causes or at the hand of the Pueblos is unknown. Four years later, the new governor, Don Diego José de Vargas Zapata Luján Ponce de León y Contreras, led a retinue of 60 soldiers, 100 loyal Indians and several friars back to Santa Fe, arriving on September 13. The Pueblos at Santa Fe welcomed the Spanish, and by December, when Vargas returned to El Paso for more soldiers, over 2,000 Indians had been baptized.

Following Vargas’ arrival in Santa Fe late the next year, a number of Pueblos again sought to drive the Spanish out, but this time, they failed. By December 1696, all rebellion had been quashed.

Although the Pueblos were again under Spanish rule, their rebellion had ushered in a time of prosperity for the Indians of the Great Plains and Northwestern plateau country. As more and more tribes obtained the horses (or their offspring) that Popé had ordered out of New Mexico, intertribal trade increased and living standards rose. The first eight decades of the 18th century were the apex of the American Indian renaissance, a time of plenty that would be abruptly ended by the great smallpox epidemic of 1780-81.

Photo Gallery

– All photos courtesy True West Archives unless otherwise noted –

– Courtesy Museum of New Mexico, Neg. No. 11409 –

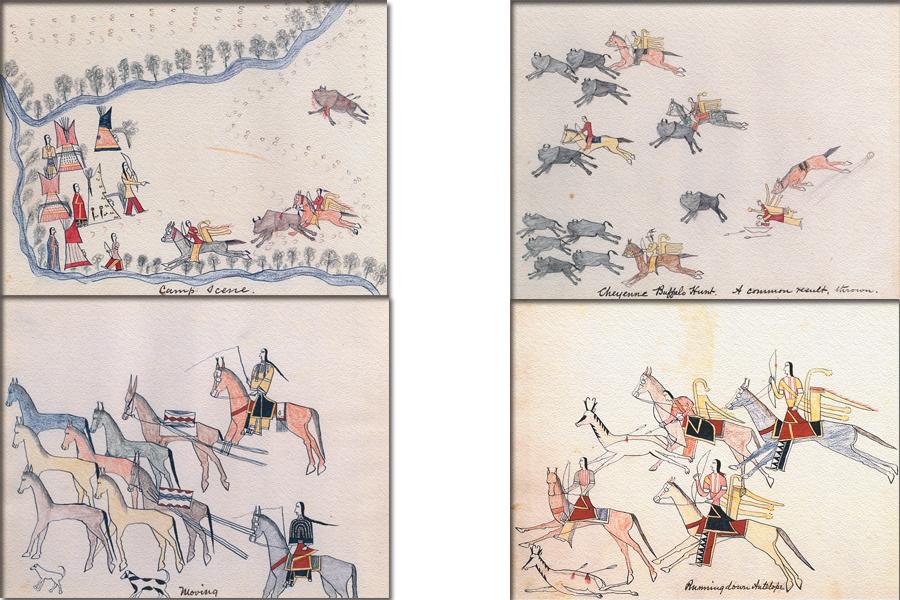

In 1875, the federal government imprisoned leading warriors of four tribes in hopes of quelling Plains Indian unrest. While a prisoner at Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida, 33-year-old Cheyenne warrior artist Making Medicine created ledger drawings showing how Plains Indians depended on horses for their survival.

(From top left) Near camp, Indians on horseback hunt buffalo, while the next scene shows a rider thrown from his horse during the hunt. In order to kill the buffalo, riders must catch up to the herd, but sometimes while riding at full gallop, horses stumbled in prairie dog holes, as indicated in this drawing where the hoof print is drawn inside a circle (center right edge). Because the Cheyenne were dependent on the buffalo, they had to follow the wandering herds. In this next drawing, you can see horses dragging travois, which were crossed tipi poles used for carrying the Indians’ belongings. But the buffalo was not the only animal Cheyennes hunted from horseback, as shown in Making Medicine’s drawing of Indians riding down antelope.