Sam Fuller made his first movie about a sullen loser, Robert Ford, instead of a two-fisted hero, a singing cowboy or an outlaw. Lucky for Fuller, I Shot Jesse James did well at the box office.

Sam Fuller made his first movie about a sullen loser, Robert Ford, instead of a two-fisted hero, a singing cowboy or an outlaw. Lucky for Fuller, I Shot Jesse James did well at the box office.

John Ireland was always a tough actor to read; it was hard to tell if he was smiling or grimacing, deep in thought or merely confounded. But that quality works in I Shot Jesse James because the audience find’s Ford’s center without road signs.

Fuller is more than a little sympathetic toward Ford. “I happen to like Robert Ford,” Fuller said in an interview in 1969, “because he did something which should have been done quite a bit earlier in the life of Jesse Woodson James.”

Ford’s motivation for killing Jesse James is pretty simple: He’s desperate to quit the outlaw life and marry his sweetheart, and he thinks that the government’s offer of a pardon and a $5,000 reward are the ticket. But to quote Walter Neff from the 1944 movie Double Indemnity, “I killed him for money—and a woman—and I didn’t get the money and I didn’t get the woman. Pretty, isn’t it?”

This is a particularly good time to watch I Shot Jesse James because it overlaps at points with the last part of The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, particularly in the scene where Ford is forced to stand in a saloon and listen to a troubadour sing the famous song about the “dirty little coward.” The similarities are interesting, but the differences are remarkable.

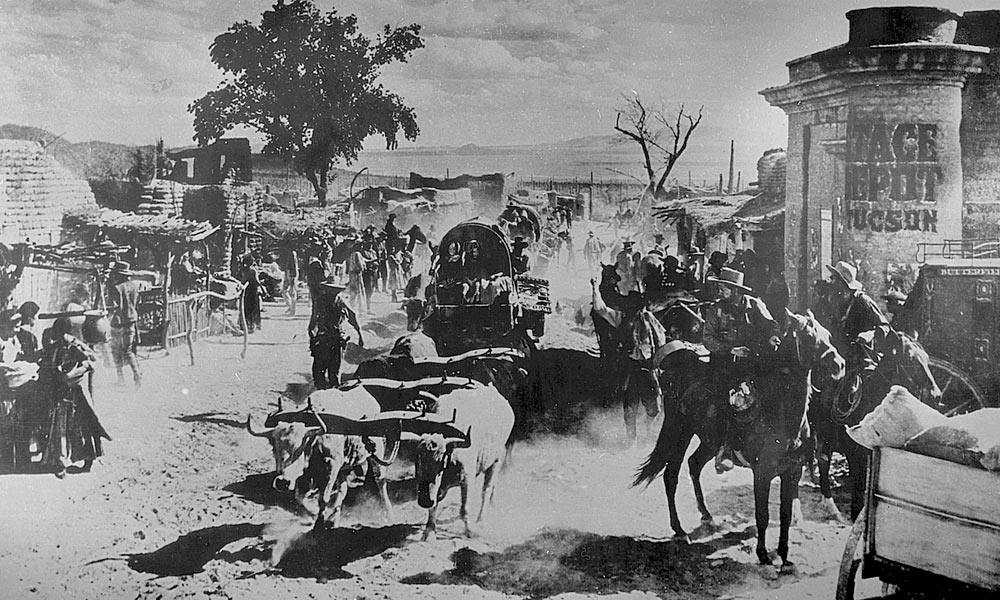

The Baron of Arizona, the other Western film in the collection, is based on the true story of James Addison Reavis, who, in 1883, laid claim to 18,000 square miles of the Arizona Territory and New Mexico. Reavis nearly got away with it.

Reavis (Vincent Price, in his second-best, ham-free performance) lays out a master plan that will take a decade to complete. He must create a false heir out of a peasant girl and spend three years at a monastery in Spain, working his way to a position in the library so he can forge an entry in the land records. That’s dedication.

While Reavis is abroad, tutors turn the young girl into a Baroness. Reavis makes the girl the legal heir to the land and then marries her. Nobody but Reavis knows the entire thing is a con. Then we get one of Fuller’s trademark skids: The much older con artist and the woman who was a child when he left, actually fall in love.

Meanwhile, the locals, who have been scratching out a living, fighting Apaches and the desert heat, don’t take too kindly to being taxed, dispossessed and lorded over by some high-falutin guy in a cape. Hilarity ensues for the good people of the territory, and it requires some rope and a noose.

Truth be told, this feature is a lesser Fuller.

Overall, though, this collection is a great place to learn about the guy who said, “Film is a battleground. Love, hate, violence, action, death…. In a word, emotion.”