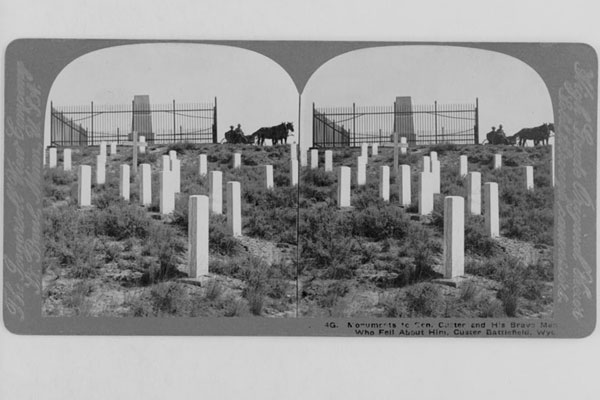

He is the one living connection to the Battle of the Little Bighorn, or Custer’s Last Stand if you prefer.

He’s an old man now, 96 on October 27. His hearing is bad, his eyes are weak and he’s been sick a fair amount in the past year.

But Joe Medicine Crow’s mind is clear and his voice is strong as he tells the stories of that hot and dry day—June 25, 1876—when a large force of Indians destroyed the U.S. 7th Cavalry in southeastern Montana. Medicine Crow heard the stories from the men who were there, both Custer foes and allies.

Voices of the Elders

Medicine Crow’s mind retreats to 1920, when he was six or seven and living near Lodge Grass, Montana, about five miles from the battlefield. In the fall and spring, the old men gathered in the sweat lodges to purify their bodies and minds, to reminisce about the past and mourn for its loss.

Usually, they recounted their bravery in battle. As you might expect, the Little Bighorn was a favorite subject.

One of those men was his grandmother’s stepbrother (stay with us here), who by Crow tradition is also considered his grandfather. White Man Runs Him, born around 1858, was one of Custer’s scouts on the ill-fated mission. He took the boy Joe to the lodges to hear the tales.

The elders said the problems began before the fighting started. “White Man Runs Him insisted that Custer’s soldiers had been drinking that day,” Medicine Crow remembers. The men of the 7th weren’t ready for a tough fight.

Then the scouts went to a high point of rocks to spy on the Indian encampment—and realized that they faced several thousand warriors (just how many is still unclear). Custer didn’t really believe them, and he certainly wasn’t fazed; his only concern was that the Indian force might escape before he could get to them.

“Custer did not take the advice of his Crow scouts, who told him to wait for reinforcements before attacking the Sioux and Cheyenne camp,” Medicine Crow says. “Instead, he divided his force of 700 soldiers into three parts and attacked right away.” The scouts knew what awaited; they began changing from army uniforms into their native clothing and singing their death songs. Custer asked an interpreter to explain the Indians’ actions. When he was told, Custer accused them of being cowards and sent them away. That saved their lives.

The last White Man Runs Him saw of Custer and his detail, they were charging toward the Little Bighorn River, heading for the huge Indian village—estimates range from several hundred lodges to a couple thousand—and the stuff of legend.

At that point, White Man Runs Him said, “we went back along the ridge and found [Maj. Marcus] Reno’s men entrenched there. We stayed there all afternoon,” fighting off the Indians. When darkness fell, the scout made his way through enemy lines and found troops coming to support Custer.

It was a story that Joe Medicine Crow would hear many times.

They Didn’t Want to Hear

Frequently, the young man served as interpreter for his grandfather, especially when white newspapermen and writers came for interviews about the Custer fight.

Medicine Crow says that most refused to believe the stories, which flew in the face of the white image of Custer as a brave fighter who was ambushed by savages. Finally, White Man Runs Him had his fill: facing a skeptical interviewer, he told the boy in Crow, “Send him home. He does not want to know the truth.” The mid-60s man rarely spoke of the battle to whites after that.

Medicine Crow faced similar disbelief throughout the years yet he didn’t stop telling the Crow stories.

Feet in Two Worlds

Medicine Crow’s relatives were not afraid to face the truth—the younger people would have to live in the white man’s world. So while they brought them up with the old customs—speaking the Crow language and learning the way of the warrior—the elders sent the children to white schools. It was tough, Medicine Crow says. The Indian kids faced physical and emotional bullying from their mainly white peers, and either indifference or discrimination from the teachers.

Most dropped out. Medicine Crow stayed, but he didn’t get his high school diploma until he was 21 years old. Then he became the second member of the tribe to attend college, and the first to obtain a graduate degree, earning a masters in anthropology from the University of Southern California. He was well on his way to a PhD when WWII interrupted. Combat action in Europe provided an opportunity to bring his two worlds together—and to prove his own worth as a warrior.

In early 1945, Medicine Crow and the 103rd Army Division were driving through Germany, trying to finish up the war in Europe. He put war paint on his arms and a sacred eagle feather under his helmet, believing the strong medicine would protect him. It apparently did more than that. In an era of advanced warfare, Medicine Crow accomplished four tasks required of a Crow war chief—steal an enemy’s horse, touch an enemy in battle, take away an enemy’s weapon and lead a successful war party. Nobody since has achieved that honor. It probably won’t be done again.

To this day, he proudly tells stories of his accomplishments in battle—just like White Man Runs Him and his other ancestors did.

A 21st-Century Crow

More honors have come Medicine Crow’s way over the years, including his receipt of this year’s Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor. He’s written numerous books and articles, and given more interviews than one can count.

In the oral tradition of his Crow tribe, he passes the stories on to younger generations—Indian as well as white—who need to understand their history and culture if they are to be successful in the modern world. Joe Medicine Crow has already blazed that path, a nearly 100-year journey filled with great achievements.

Photo Gallery

I served on the Little Bighorn Monument advisory commission, which was to establish an Indian memorial at the Little Bighorn. And we had very studiously avoided using the word “Custer” anywhere. Custer’s name was to be eradicated in all of our deliberations. There would be nothing in this to memorialize him.

[In November 1999] we were doing the groundbreaking. And Leonard Bruguier, who was head of American Indian Studies at the University of South Dakota and the chair of the commission, was giving a speech.

Up from the crowd comes Joe Medicine Crow, dressed in his WWII uniform. He walked up to Bruguier and said, “I’ve come to sing an honor song for Custer.” A hush came over the crowd. Leonard graciously stepped aside, and Joe sang this wonderful honor song for Custer in both Crow and English.

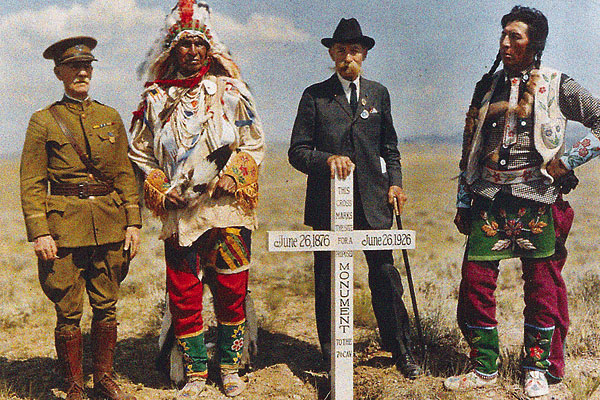

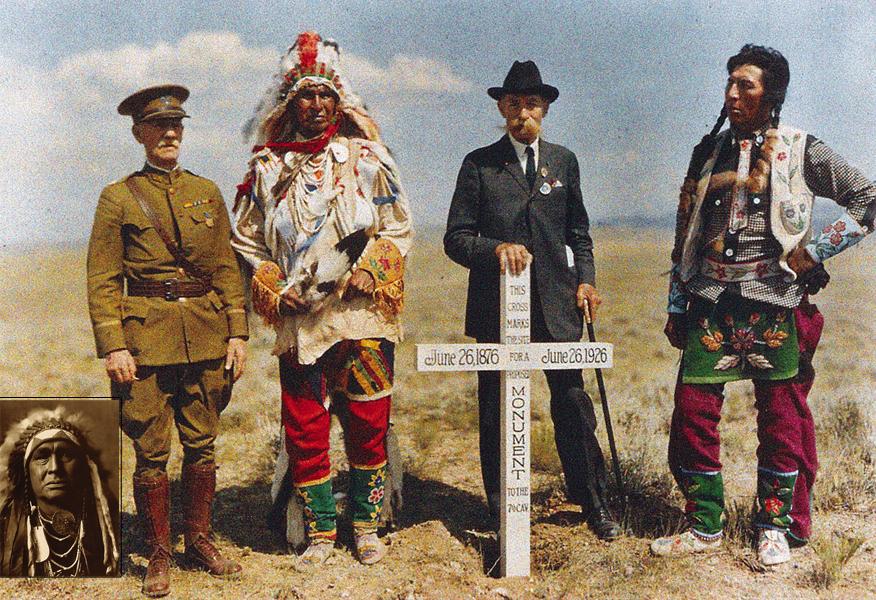

—Historian Paul Andrew Hutton, on Joe Medicine Crow’s work to bridge the divide between Indians and whites; shown here is the 1926 gathering, with White Man Runs Him shaking hands with Gen. E.S. Godfrey.

— All images courtesy Chris Kortlander —

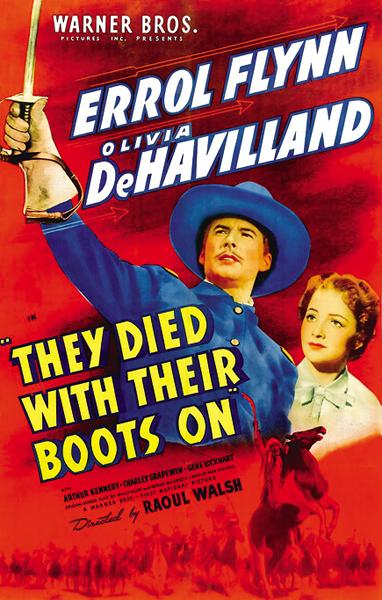

In 1941, Joe Medicine Crow was undergoing his graduate study at the University of Southern California when he saw an ad in The Los Angeles Times. Warner Brothers was casting extras for the Custer film They Died With Their Boots On.

Medicine Crow thought it might be fun (and provide some pocket change), so he attended the audition. The producers were delighted to have an Indian show up, and even happier that he had actual connections to the Little Bighorn battle. They asked him to help with the script.

Medicine Crow’s efforts did not work out. The powers that be threw out historical accuracy in favor of a pro-military, patriotic approach, believing (correctly) that the U.S. entry into WWII was coming fast. Their Custer (played by Errol Flynn) would be a heroic figure, sacrificing himself for his country.

When Medicine Crow told the producers that their depiction was way off, they fired him.

“I said, ‘Some day I’m going to write my own Custer production and tell it like it is.’” Medicine Crow grabbed his chance in 1964, when he authored the script for the Little Bighorn re-enactment that still runs each June in Hardin, Montana.