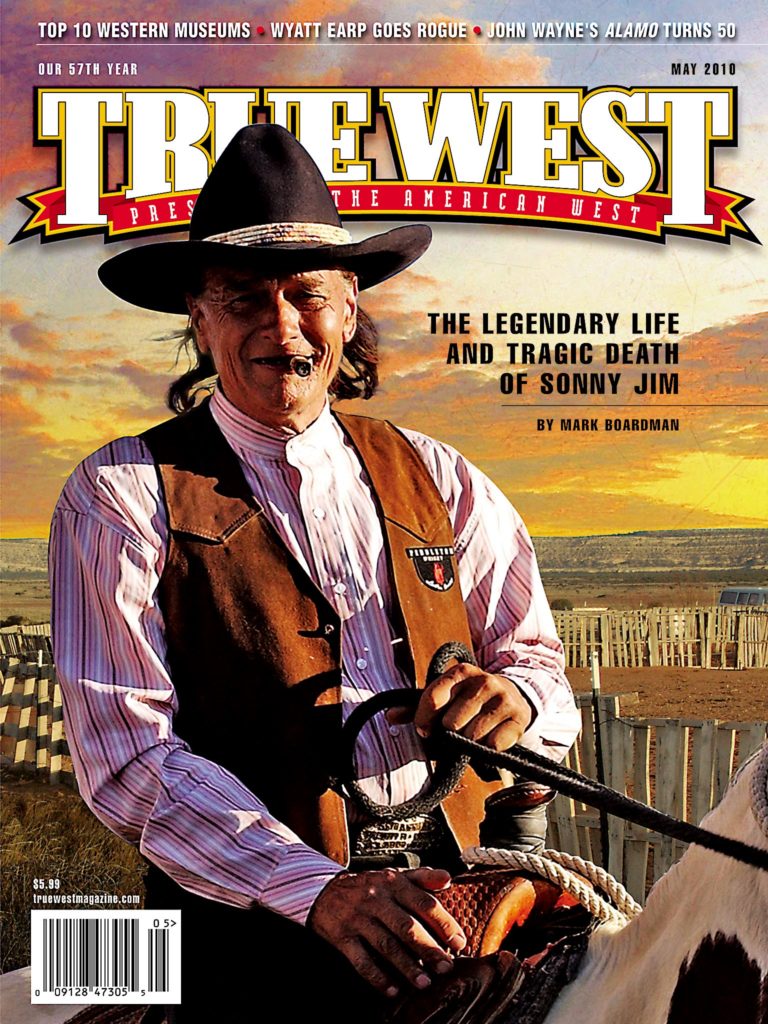

About 1,000 people came to praise the old Indian cowboy, not bury him.

They came from far and wide, from California to Oklahoma to Oregon and more, braving the late October cold and snow and icy roads to sing songs and swap stories. They were professionals, housewives, cowboys, Indians and Hispanics and whites. They were friends and kin and admirers of the man who called himself Sonny Jim, who many said was one-of-a-kind. He’d packed two or three lifetimes into his 68 years—and yet he died way too early, a peaceful soul victimized by senseless violence.

“He lived in the Wild West and died in the Wild West way,” his friend Sammy C. said that day.

By the time those people gathered for his memorial service—October 29, 2009, at Red Rock State Park near Gallup, New Mexico—Sonny Jim was already a legend in many parts of the West.

You probably haven’t heard of him. It’s high time you did.

Sonny Jim was an impressive guy. He would have been the perfect cover model for a New West magazine—not only in his dress, but also in his physical attributes. He was remarkably handsome, and at 6’1″ and 200-some pounds, standing straight as an arrow and moving with the gracefulness of a mountain lion, he looked like an athlete. But even more important, he greeted everyone with a winning smile and with kind words. He listened intently, making folks feel special. People were drawn to Sonny Jim, and he to them.

He was born Clyde Shacknasty James at the Klamath Indian Agency in Oregon on December 28, 1940. His mother Luella—the daughter of German immigrants—exposed the youngster and his three sisters to music, the arts and their Modoc heritage. Father Clyde passed on athletic talent, a love of basketball and a dedication to the cowboy way. He had Sonny Jim throwing rope around the house as soon as the youngster could walk, and he was on horseback at about the same time. Sonny Jim worked on those skills hour after hour, day after day. It was an eclectic household. And Sonny absorbed it all.

The family moved to Taos, New Mexico, when Sonny was in junior high, and he began hanging out with his half-brother Woody Crumbo Jr. A cowboy named Slim Evans took a shine to the boys and put them on several of his horses—”I can’t tell you how many times our butts hit the ground,” Woody says.

Slim’s nephew Max also took an interest in the kids. At the time, Max Evans was a noted artist, but he was about to switch over to what would become an award-winning career in Western fiction writing. He also decided to switch cow horses, and he gave Sonny and Woody his old mount Sleepy Kay. “They started learning to rope on Sleepy Kay,” Evans wrote in his book For the Love of a Horse. “She was exactly right for them. Eventually, they turned her into a steer jerking horse.”

In his teens, Sonny Jim became a star basketball player, a noted rodeo cowboy, a talented musician and an advocate for American Indian cultures. He went back to Oregon after high school and adopted the moniker Sonny Jim to honor his grandfather. Many people would never know him as anything else—just Sonny Jim.

In the early 1960s he returned to New Mexico to live among the Navajo, partly because he married a Navajo woman and partly because the tribe had an active and competitive rodeo circuit. He also loved the tribal culture and the people; their laid back ways suited his personality and lifestyle.

Central and northeast New Mexico had their own allure too. The changing of the seasons. Long stretches of land that haven’t varied since the Old West days. Rocky buttes and mountains rising toward the sky, ringing pastures for cattle and horses, and farms for growing produce. It was all a spiritual man like Sonny could want.

The Navajo quickly accepted him. He came with an open heart and a respect for the people who call themselves “Dine.” Navajo Nation Judge T.J. Holgate—also a rodeo competitor—calls Sonny Jim an in-law, a member of the Navajo family and says that Sonny Jim was loved and respected wherever he went.

Well, for the most part anyway. Some of Sonny Jim’s competitors at the Navajo rodeos were a little suspicious of this guy with light skin and white facial features; they made him produce his tribal registration papers before he was allowed to ride. But that quickly blew over.

The old Modocs prized great speakers and orators above all others. They weren’t alone in that, of course, and that may help explain Sonny Jim’s legend.

He was a born storyteller, and many of his tales were about his own life. Now that had its problems. A great storyteller often won’t let the facts get in the way of entertaining the audience, and Sonny was no exception. Even members of his own family weren’t sure which of his stories were true.

He claimed to have toured Asia with the Harlem Globetrotters during the early 1960s, playing for their traveling opponents and also giving presentations on American Indians.

Sonny said that he played backup guitar for both Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings in the early 1970s.

He was involved in the American Indian Movement in the 1970s, working to expose the plight and support the rights of American Indians.

He was trained as a medicine man, and many in the community considered him a gifted healer of body and soul.

He told how he’d won the national all-around Indian Cowboy title in 1969 and ‘70, was the top Indian bareback rider in 1970 and the steer-wrestling champion in 1982—at the advanced age of 41.

All of those stories turned out to be…true.

But Sonny also hedged on some small points, like his real age. For years, a lot of folks thought he was 10 years younger than he actually was.

Those kinds of sketchy details just added to the Sonny Jim mystique. Folks knew the stories, but they didn’t know everything about the storyteller. That’s how he wanted it.

Part of the legend came from the life he led. Sonny Jim was a travelin’ man, a seeker who wandered the West in search of meaning and the perfect rodeo ride. His half-brother Woody says the road was Sonny’s home—clichéd, perhaps, but true.

At this point, it might be instructive to consider four years in the life of Sonny Jim.

In 1978, a 17-year-old Papago (now Tohono O’Odham) from Arizona named Sy Johnson finally met the man he’d heard so much about. Sonny Jim was a larger-than-life figure, and the angry, rebellious teen was drawn to him. The feeling must have been mutual; Sonny invited Sy to go with him on a journey. The kid quit school, packed some bags and headed out.

Over the next few years, the two moved across the West, competing in rodeos and taking odd jobs to pay their expenses. For a few months between the end of November and the start of April, they would return to their homes, ranching and cowboying and doing whatever else needed to be done.

Sy remembers that it was a hand-to-mouth existence, simple but satisfying. They’d sleep in the open, just like their ancestors had. They’d often hunt for their food. Some weekends they’d hit four or five rodeos—sometimes getting rodeo groupies to chauffeur them in the girls’ cars (“They were a lot more comfortable than our truck.”). Sonny was a good-looking guy, and the ladies found him to be charismatic.

But Sy took away more than memories and belt buckles. “I was a kid, and I had long hair and didn’t get along with many people. Sonny Jim taught me to have pride in myself as a person, and to have indigenous pride in my heritage and my people. He changed my life.”

He’s not alone in that statement.

For Sonny Jim came into contact with countless people over the years. He grew close enough with many that he considered them family; it’s unclear just how many folks he called adopted sons or daughters or brothers or sisters (he considered Sy Johnson an adopted little brother). He didn’t need a government document to prove it (in fact, he didn’t care very much for government documents in general). But they were family, every bit as much as his eight children and 18 grandchildren.

Talk to folks about Sonny Jim and you’ll hear the same comments over and over again. Unique. A free spirit. Incredibly talented at everything he did. An Old West cowboy who should have been born 150 years ago. A wonderful guy.

Some also think he had a gift of healing. Author Max Evans was the biggest believer of all, saying Sonny Jim had the strongest capacity of medicine than just about anybody he’d encountered. For decades, he urged Sonny Jim to give up the rodeo and focus on being a medicine man. Sonny would promise to do so—after the next contest. Or the contest after that. Or the one after that. “He just couldn’t give up the rodeo, even though he knew he should,” says Woody Crump Jr. “It was too much in his blood.”

All of them remembered Sonny Jim with his trademark stogie, whether he was bulldogging or roping during Indian rodeos, or shooting the breeze with folks. He even had one clenched in his teeth that fateful October day.

His daughter Sonlatsa Jim-Martin—Sonny called her Sunshine—says that her dad would give anything to people in need, from money to clothing to knowledge and advice to physical help.

Part of that was his caring nature. But his sister Cheewa James says that Sonny had no modern conception of material things or money; they just didn’t mean anything to him, so it was easy to give them away.

Ironically, that life approach contributed to his death.

Sonny was good friends with Wayne Johnson, a rancher with a spread just outside San Rafael, New Mexico (about five miles south of Grants and an hour southeast of Gallup). Johnson was 75 and in failing health; Sonny often took him to doctor’s appointments and helped out around Johnson’s ranch. A grateful Johnson began drawing up documents to give his land to Sonny.

To be honest, it wasn’t much of a spread, just three or four acres on a windswept plain, surrounded by other, mostly empty plots. Johnson’s land was and is a mess—a half dozen or so beat up cars, three decrepit trailers of various sizes and makes (Johnson lived in the blue trailer), some sheds and chicken coops and assorted trash. The place looks like a junkyard.

To make matters worse, some Navajos consider the San Rafael area to be a dark place, full of negative energy.

But the land was Johnson’s, and he wanted to give it to Sonny. The two of them had to take care of a problem first.

Back in 2005, Johnson allowed a drifter named Danny Stanfield to squat on his land, living in an old bus that Stanfield had been driving around. The relationship cooled over the years; by the middle of 2009, it was positively sour.

On the afternoon of October 23, 2009, Johnson, Sonny Jim and his ranch hand Fernando Begay went to tell Stanfield that he had to move. Johnson had asked Sonny to go with him, in part because Sonny was younger and in good shape, just in case they ran into trouble, but also because Sonny was a renowned negotiator and peacekeeper who could talk his way through anything.

When they got there, they tore down a fence that Stanfield had put up on the property. Stanfield came out and started arguing with Johnson. Then he headed back into his bus. When he returned, he wore a .38 Ruger holstered at his hip. Sonny Jim pulled out his cell phone and called 9-1-1.

Stanfield drew his gun with one hand and a pair of handcuffs with the other, telling Johnson and Sonny Jim that they were under citizen’s arrest. Just what happened next is a bit fuzzy. But apparently Sonny—still on the phone—made a slight move toward Stanfield, who opened fire. Sonny was hit in the chest. Stanfield turned and shot at Begay, who was running for his life down a nearby road. Those shots missed. Stanfield then went after Johnson, who was grabbing for a small derringer, and shot him. Stanfield reloaded the Ruger and shot both men again, once each in the head.

Sheriff’s deputies arrived on the scene within minutes. As they approached Stanfield, he tossed the holstered gun down and yelled, “You’re damn right I shot them! It was self-defense.”

The evidence and Begay’s testimony showed otherwise. Stanfield was arrested and indicted on several counts, including murder. As of press date, he was in jail awaiting trial.

Just the weekend before, Sonny Jim had competed in bulldogging, overcoming an injured right shoulder to participate. And he was 68 years old.

At Red Rock State Park, six days after the shooting, Sonny Jim’s memorial service closed with his widow Bobbie leading his saddled horse around an outside arena—the symbol of his last ride. The snow fell, and his Navajo friends called it a good sign, since the flakes were nourishing the land with water.

Then his protégé Matt Vail burst out of a gate and charged his horse after a steer, remembering Sonny Jim’s life in rodeo. At that moment, the snow stopped and the sun came out. That’s considered a sign of good fortune for all involved.

Only at Sonny Jim’s funeral….

The Modoc believe that when a person dies, his life force goes west of the mountains (probably the Cascades of northern California).

Sonny Jim has got to be an exception. His spirit was always just too free to be contained in one place.

Maybe his life force will follow his ashes (his body was cremated, in the Modoc tradition). Over the next year or so, Sonny Jim’s family plans to visit certain spots in the West that Sonny believed were special and sacred, sprinkling some of his earthly remains at each location—places that are not bound by time or space.

The Indian cowboy has gone home.