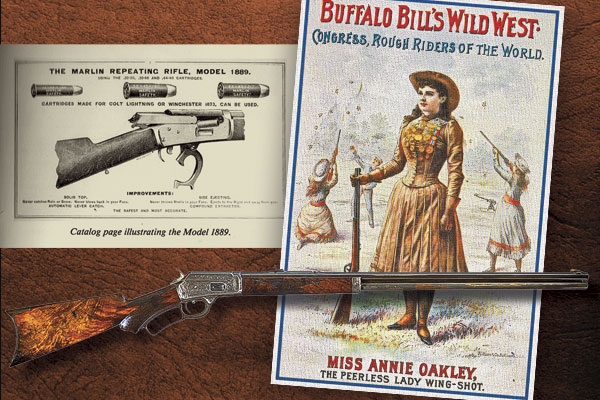

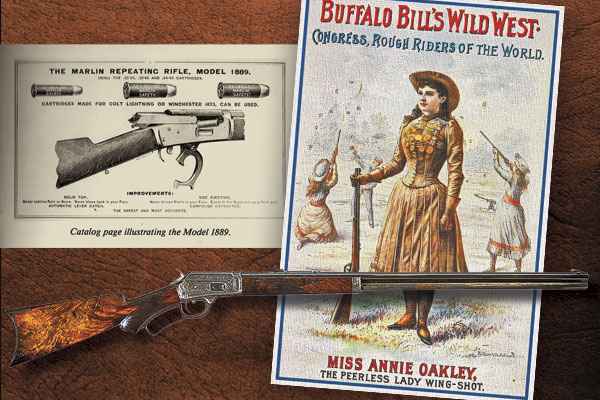

World-renowned sharpshooters Annie Oakley, a star of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, and Frank C. Miller, crack shot of the Irwin Bros. Cheyenne Frontier Days Wild West Show, often shot with Marlin rifles in their exhibitions.

World-renowned sharpshooters Annie Oakley, a star of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, and Frank C. Miller, crack shot of the Irwin Bros. Cheyenne Frontier Days Wild West Show, often shot with Marlin rifles in their exhibitions.

“I gave as high as 15 exhibitions a day, shooting under all conditions, rain, wind, night, in parades in the streets,” Miller said in a 1915 interview. “And late last fall, I used some of the guns on a hunting trip to Canada and Wyoming. From all this, you can see what opinion I have of Marlin guns.”

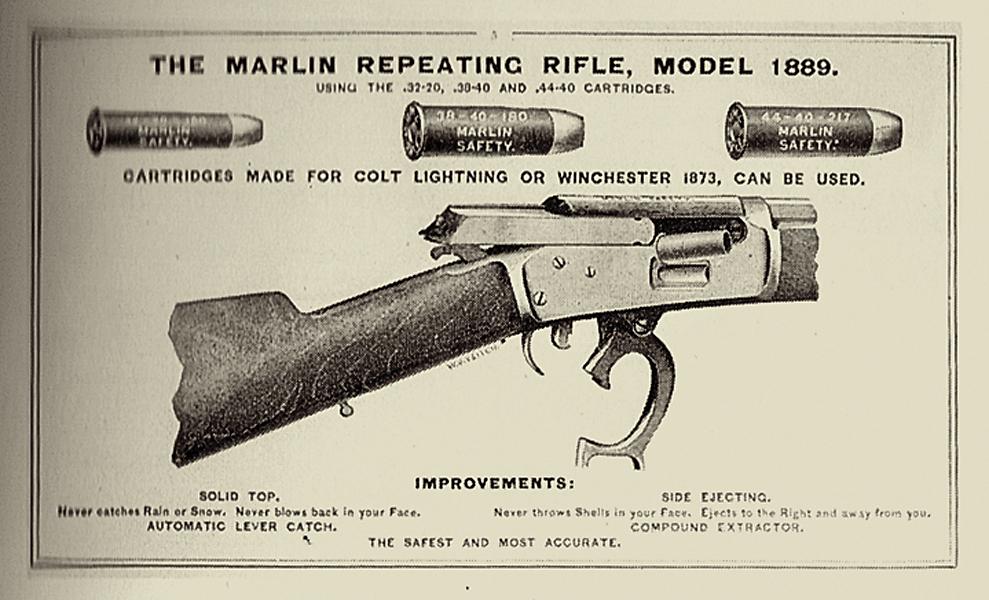

Among the several Marlin firearms Oakley owned, she particularly cherished a special presentation, engraved 1889 model. The ’89 Marlin was the first solid-top receiver, lever action rifle with a side ejection that threw the fired cases, or live cartridges, to the right-hand side of the rifle as opposed to being thrown straight up and out of the gun.

Dubbed as the “New Safety Repeating Rifle,” the 1889 Marlin was a mid-sized, redesigned 1888 model. The most noticeable difference was the solid top with its side-ejection system. Internal upgrades included a locking lug and firing pin system that prevented discharge until the bolt was locked in place. The new model also utilized a cartridge carrier that raised automatically, closing the end of the magazine after the head

of the cartridge had passed into the carrier, thus preventing the next cartridge from entering the carrier and jamming the action—an important feature, since the rifle was produced in the .32-20, .38-40 and .44-40 chamberings (only 34 made with .25-20).

The similarity between the .38-40 and the .44-40 cartridges sometimes caused confusion for shooters. If a shooter accidentally loaded a .44-40 into a .38-40, the lever would not close properly. With the ’89 Marlin, he simply had to lever downward, as if the .44-40 was an empty shell, and the oversized cartridge would be thrown to the side.

Standard ’89 Marlin rifles included a 24-inch octagonal or round barrel,

although barrels could be ordered in intervals of two inches up to 32 inches. The 1889 was Marlin’s first carbine. Standard carbines had 20-inch tubes, while around 300-plus were made with a 15-inch version, and just four were turned out with 24-inch barrels.

Rifles were fitted with “Rocky Mountain” sights made up of a German silver blade front sight and a semi-buckhorn-type rear sight, which could be elevated by a stepped elevator. The stock was straight-grained walnut with a steel-capped forearm and a crescent-style steel butt plate (carbines wore a carbine-style butt plate). Barrels and all hardware were blued, while the hammer, lever and butt plate wore the colorful Marlin case-hardening. The model also came as a short rifle, takedown model and musket.

Although somewhat revolutionary in the firearms world, the ’89 still had minor drawbacks that would be eliminated from Marlin’s subsequent models. The manufacturer removed the rear-locking lug, which extended down into the trigger guard and had a tendency to pinch the shooter’s fingers during rapid-fire cycling. It also did away with the small spring-loaded retainer at the rear of the lower tang that held the lever in place when closed, which shooters disliked.

Nevertheless, the 1889 Marlin was well received on the frontier and nationwide. More than 55,000 guns left the factory between 1889 and 1903. In its day, the model was considered state-of-the-art. Now, 125 years later, the 1889 Marlin is an extremely collectible firearm.

Phil Spangenberger has written for Guns & Ammo, appears on the History Channel and other documentary networks, produces Wild West shows, is a Hollywood gun coach and character actor, and is True West’s Firearms Editor.

Photo Gallery

– True West Archives –

– True West Archives –

– Courtesy Rock Island Auction Company –