– Courtesy Photofest –

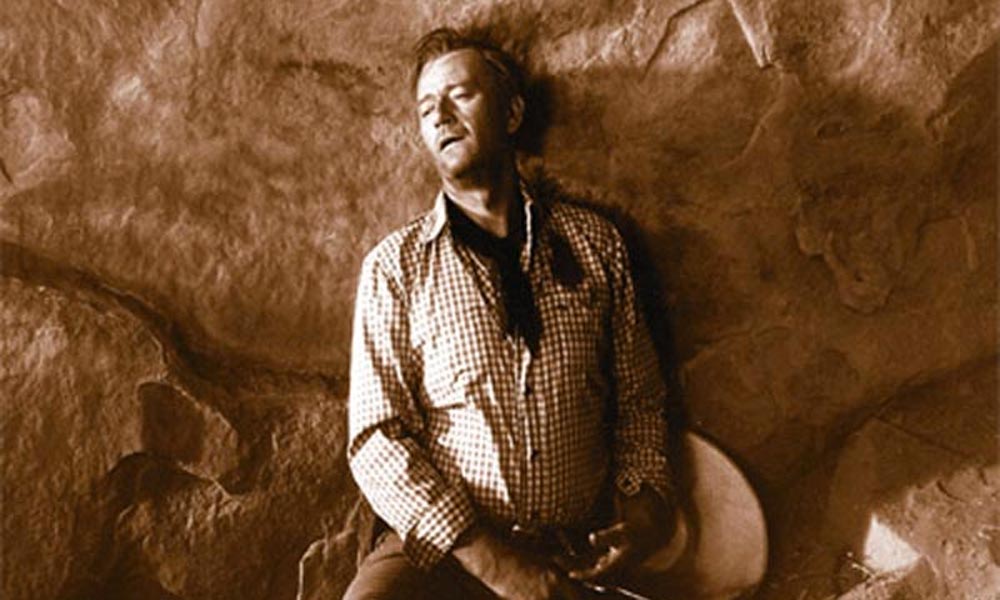

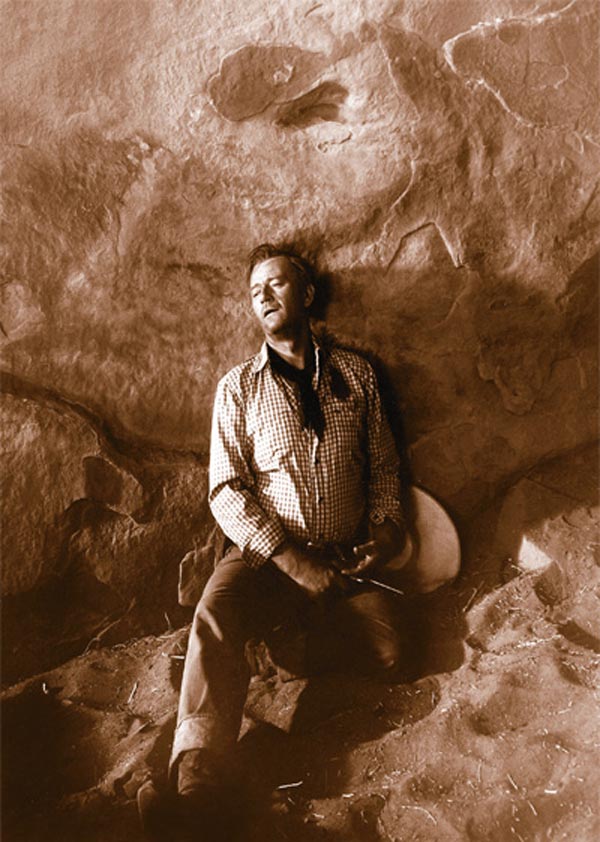

The Searchers is a surprisingly complex film, even by today’s standards.

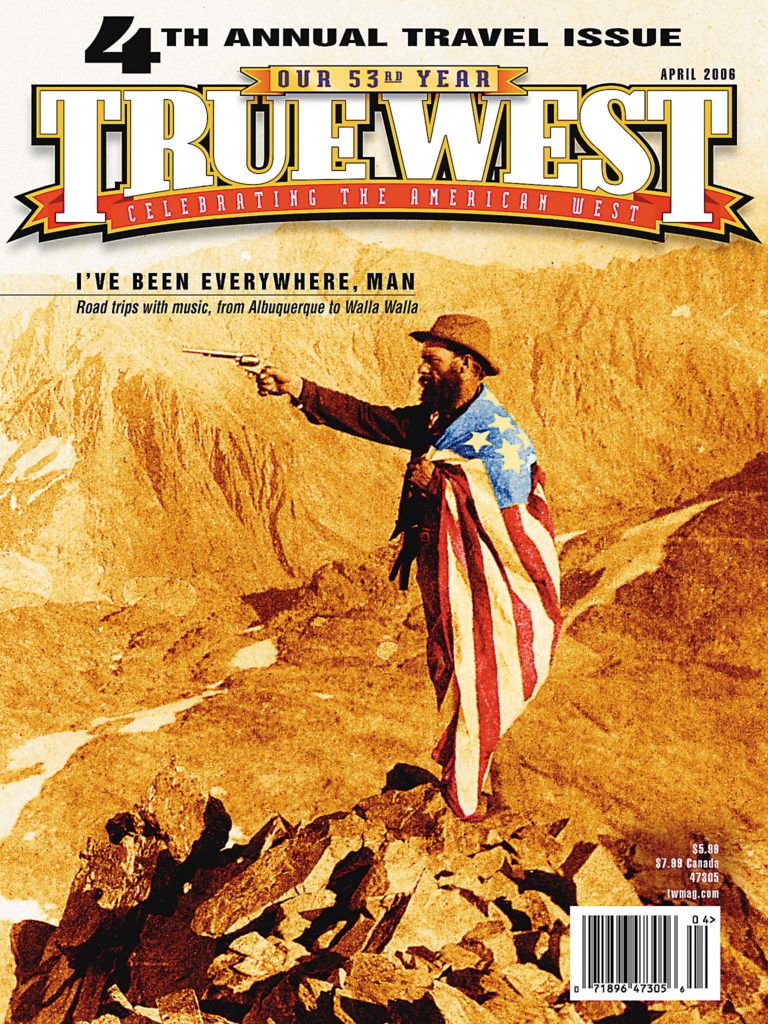

A film widely considered to be the greatest Western ever made turns 50 this year. This anniversary provides an opportunity to reflect not just on the film’s legacy, but also on what it tells us about how we look at our own history.

A simple story of two men on a quest to rescue a girl captured by the Comanche, The Searchers is anything but simple. Unusually stark, the movie is raw and grim. Emotions are on the edge, whether characters are suffering the pain of unrequited love, harnessing the courage and determination to make a go of it on the frontier, or indulging deep hatreds. The cinematography is vibrant and rich, with oranges, blues and reds, contrasting lights and darks, vivid shadows. Hot wind, dust and skeletal rock formations pierce the sky to complete the visual effects, underscoring the film’s themes of the precariousness of life and the cost, both societal and personal, of irreconcilable cultural conflict.

In 1955, when John Ford marshaled his “stock company” of actors, stuntmen and crew to make his fifth of seven Westerns set against the magnificence of Monument Valley, there was a sense they were creating something unique. Harry Carey, Jr., describes the set as unlike any he had ever been on. John Ford “was much more serious,” he writes, “and that was the tone that pervaded the cast and crew.” Of John Wayne, he remembers, “When I looked up at him in rehearsal, it was into the meanest eyes I had ever seen…. He was even Ethan at dinner time. He didn’t kid around on The Searchers the way he had done on other shows. Ethan was always in his eyes.”

Indeed, what makes The Searchers truly unusual is not so much its plot or cinematography, but its main character. At the heart is a brooding, angry, embittered John Wayne hero. He shares many attributes with the traditional Man of the West—tenacity, persistence, determination, courage, skill, strength—but in many ways he is the antithesis of heroic behavior. He is vicious, shooting retreating Comanche warriors trying to pick up their dead and wounded; he is caustic, treating his nephew with contempt, calling him “blankethead,” “half-breed”; he is bloodthirsty, scalping Comanche chief Scar toward the end of the film. He is filled with rage and race hatred, is bitter, antagonistic and obsessive—a rarity in any Western hero, before or since.

But reviews at the time were mixed. Bosley Crowther of The New York Times called The Searchers “a rip-snorting Western, as brashly entertaining as they come.” Variety, however, found it “somewhat disappointing. There is a feeling that it could have been so much more.” For the reviewer at the New York Herald Tribune, the pace was slow and ponderous. “The search sometimes seems to literally take five years instead of just two hours,” he wrote, “and at one point when the movie is approaching a compact conclusion, it veers into another tack and meanders into a long, flabby ending.” The Nation, offended by the Wayne character, called it “a picnic for sadists in very beautiful country.”

The Searchers was not nominated for a single Oscar. In fact, no Western had won the Academy Award for Best Picture since 1931’s Cimarron—not Stagecoach, not Shane, not High Noon. It wasn’t until the early 1970s, when a few scholars began looking seriously at Westerns, that The Searchers started to gain critical recognition. In 1972, it ranked 18th among critics on a list of the greatest films ever made and would be fifth on that list in 1992. The film also influenced a generation of prominent directors, from George Lucas (Star Wars) to Martin Scorsese (Taxi Driver) to Steven Spielberg, who filmed his own two-reel version of The Searchers in a friend’s backyard when he was in the seventh grade.

– Courtesy Photofest –

Abduction of Cynthia Ann

But the legacy goes further than motion pictures. The Searchers is a mirrored self-image, a look at the strength of pioneers in that most arid and unforgiving environment of Texas in 1868, but also an often uncomfortable study of what it took to survive and prevail. Surprisingly, the film fares quite well when judged against what we know of life on the mid-19th-century Texas frontier. Small details, such as the ad hoc recruitment of Texas Ranger companies, the fact that Indians wouldn’t kill anyone they deemed to be crazy, even the biting and eye gouging of frontier fighting, all ring true.

On a broader level, the film also draws on historic events. One of the most publicized cases of Indian abduction during that era involved Cynthia Ann Parker. In 1836, her family was attacked by a mixed band of Indians. Killing the adult Parker men, she was taken, along with five other members of her family—her mother and aunt as well as two young siblings and a cousin (a year-old baby girl who wouldn’t stop crying, so the warriors killed her by smashing her head against a tree). Cynthia Ann was nine years old.

Within six years, the Parker family managed to ransom all surviving members except Cynthia Ann. But her uncle Isaac crusaded tirelessly for her return, writing letters to newspapers and Texas Republic congressional members, speaking passionately at church and school meetings, raising reward money and continually agitating for the formation of Ranger companies to go and find her. She was with the Comanche for 24 years when, in 1860, she was found by Texas Rangers and returned to white society. By then, she had borne three children, including son Quanah who would rise to preeminence as a warrior and later chief of all reservation Comanche.

We might think from this that The Searchers does an exceptional job remaining true to history. And while it does, there is a difference—unlike Debbie, captives didn’t always want to go home. For the next 10 years, until she died of influenza in 1870, Cynthia Ann never stopped mourning the loss of her Comanche family, nor did she learn to speak English or accept offers to rejoin the Parker family.

Whites Disguised as Indians

Historian Vernon Maddox, in addition to researching Cynthia Ann Parker’s life, has come across information in the Texas State Archives in Austin that shows Indians were not the only perpetrators of violence against white immigrants and isolated homesteaders. Of course we are aware of white outlaws and thieves committing crimes, but Maddox has found evidence of groups that did so while disguising themselves as Indians to deflect suspicion. This isn’t anything new to American history—remember the Boston Tea Party? But what is new is the extent and, Maddox suggests, the wide reach and ultimate purpose of some of these activities.

A typical attack occurred in 1858 in Northern Texas. Four white men, dressed as Indians with their hair dyed and faces painted, carrying guns, spears and bows and arrows, captured two families, stole their money (about $1,000 earmarked to buy cattle) and killed and scalped all the adults and children over 10 years old. A small posse of soldiers, scouts and civilians, including the famed cattleman Oliver Loving, tracked the outlaws and captured their leader, a red-haired white man. Although it was known that white men had perpetrated the atrocities, newspapers reported emotionally of Indian attack. Texas Gov. Hardin Runnels used these reports to justify his establishment of a new Ranger battalion earlier in the year and ordered Maj. John Salmon “Rip” Ford to lead that battalion across the Red River into Indian Territory to “inflict the maximum punishment.”

About 220 miles into Indian Territory, in direct violation of U.S. Army policy prohibiting any white person trespassing into that area, 100 Rangers came upon a Comanche village near Antelope Hills. Ordering the attack, Ford led his men into the village, firing on warriors as women and children fled. Maddox tells us that, at the time, the Rangers counted 76 warriors killed and 18 women and children captured. But that isn’t what Ford stated later. “In letters written to friends,” Maddox says, “Ford reported that he actually had captured more than 60 Comanche women and children. Historians speculate that Ford and the officers sold the uncounted women and children as slaves.”

Two years later, a detachment of U.S. Cavalry pursuing a group of horse thieves killed one as the outlaws scattered into cuts and ravines. Going through the dead man’s pockets, they discovered a letter that suggests some of these renegade white men had strong political connections and worked purposely to foment racial strife in order to justify incursions into Indian land.

In the letter, addressed to “Dear Chum,” the writer offers appreciation for a recent raid. “We are happy to know that your party succeeded so well in getting the last drove of horses from [Fort] Belknap and that you so completely fixed the affair on the Indians.” He also instructs “Chum” to have their newspaper colleague at The White Man continue inflaming emotions against Indians in its columns, and then suggests the “outlaws” find better stock in another part of Texas: “try and encourage our friends to play down the country to get a better stock of animals as the last droves were very inferior.” The letter is signed “O.L.M,” or Old Law Mob.

– Courtesy Rusty and Trish York –

What is most troubling, Maddox contends, is the suggestion that this goes far beyond a group of outlaws and thieves. The leader of the gang, he believes, was John Baylor, member of a Texas founding family and a Texas legislator. The White Man colleague, Maddox says, was the paper’s publisher, H.A. Hamner. Baylor and Hamner worked together for three years. “While they were trying to inflame the frontier,” he notes, “both men quietly dabbled in land speculation and especially coveted reservation land.”

Maddox, a retired Marine Lt. Colonel who flew 207 F-4 missions in Vietnam and spent 31?2 years as a top gun instructor at the Navy Fighter Weapons School, says he uncovered this information while he was researching general history of the North Texas frontier in the 1850-60s (he has authored two books and today teaches history at community colleges in and around Oklahoma City). Maddox doesn’t see this as revisionist history. “I just look at this as history,” he says, “looking at some things that were overlooked. I just thought how come other people haven’t looked at it this way?”

In its obsessive hero, bleak realities and cross-cultural tragedies, The Searchers, a film before its time, continues to resonate with audiences, even 50 years after its release. Maybe now we’re also ready to delve into other sides of frontier history that may not always be easy to hear but give us a more complete vision of our past.