David Crockett (1786-1836), has a tremendous responsibility.

He fills niches in American History, folklore and popular culture. Details of his life stretch thin to cover these demands. Walt Disney’s 1955 production of Davy Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier revived the frontiersman in the national consciousness after years of dormancy.

Today’s historians work hard to dispel beliefs about the man engendered by the earlier and popular ABC miniseries. Still, after hundreds of books, documentaries and movies, misconceptions persist. Some of the most outlandish claims made about him include those stating David Crockett…

Wasn’t Davy:

Crockett signed his correspondence with “David.” In print, others—including President Andrew Jackson—called him Davy. Crockett even referred to himself as Davy during a speech in Ohio on July 12, 1834.

Was lazy:

Crockett worked as a drover, freighter, farm hand, hatter, farmer, soldier, scout, magistrate, justice of the peace, town commissioner, militia officer, Tennessee State legislator, member of the U.S. House of Representatives, hunter, trail blazer for new roads, author and finally a volunteer soldier in the 1835-36 Texas Revolution.

Was uncouth:

Contemporaries described him as: “A pleasant, courteous, and interesting man, who, though uneducated in books was a man of fine instincts and intellect…a man of high sense of honor, of good morals, not intemperate, nor a gambler” (Sen. Ephraim H. Foster); “…rarely, if ever, exhibited in conversation or manner, attributes of coarseness of character that prevailing popular opinion very unjustly assign to him. I cannot recall to mind an instance of his indulgence in gasconade or profanity” (painter John Gadsby Chapman); and “just such a one as you would desire to meet with if any accident or misfortune had happened to you on the highway” (Niles’ Register, September 7, 1833).

Was of diminutive stature:

Contemporaries described Crockett as: “Tall in stature and large in frame” (Helen Chapman); “About six feet high—stoutly built” (Cincinnati Mirror and Western Gazette of Literature); “About six feet high, weighed about two hundred pounds, had no surplus flesh, broad shouldered, stood erect, was a man of great physical strength” (John L. Jacobs).

Never wore a coonskin cap:

Matilda Crockett said of her father’s departure for Texas that “He was dressed in his hunting suit, wearing a coon skin cap.” James Davis, seeing Crockett leaving Memphis for Texas wrote, “He wore that same veritable coon-skin cap and hunting shirt.” Sarah S. King recalled Alamo child survivor Enrique Esparza stating Crockett “Wore a buckskin suit and a coonskin cap.”

Abandoned his family:

Crockett left his family in autumn 1835 and died at the Alamo in March 1836. Before setting out he wrote to his brother-in-law, “I want to explore Texas well before I return.” Daughter Matilda recalled that he wanted to move his family immediately, but her mother convinced him to look the country over first. He arranged a barbecue and barn dance for family and friends before he left, hardly the actions of a man abandoning his family.

Kept a journal at the Alamo:

Richard Penn Smith created the spurious Col. Crockett’s Exploits and Adventures in Texas under Crockett’s name four months after the frontiersman’s death. Many works still cite it as Crockett’s own.

Was executed after surrendering:

The main source of his “surrender at the Alamo” is the handwritten De la Peña “diary.” Yet no record of this “diary” exists before 1955. Plus, not one page is in De la Peña’s handwriting. A number of details are obviously lifted from other sources available only after De la Peña’s death. The word “surrender” never appears in the document in regard to Crockett. A journal of the Texas campaign in De la Peña’s handwriting mentions the Alamo only in passing and Crockett not at all.

William Groneman III is the author of the 2005 biography David Crockett: Hero of the Common Man.

Photo Gallery

– All illustrations by Bob Boze Bell –

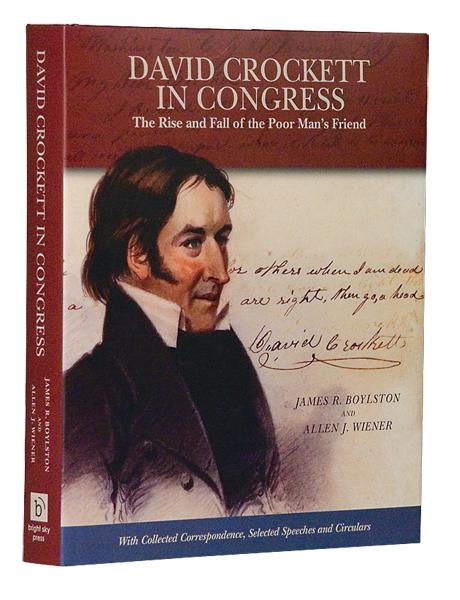

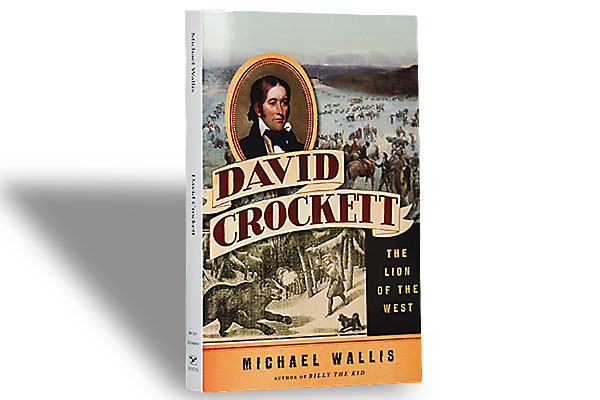

– Published by Bright Sky Press –