There were no roads; no towns. The extreme summer heat and winter cold were almost unbearable. But from a former Civil War-ambulance pulled by four sturdy mules, one of America’s greatest photographers recorded images of a 19th-century civil war, a forbidding Western frontier and the people who lived within these scenes. They still peer beyond the page, across the centuries, and into our eyes today.

There were no roads; no towns. The extreme summer heat and winter cold were almost unbearable. But from a former Civil War-ambulance pulled by four sturdy mules, one of America’s greatest photographers recorded images of a 19th-century civil war, a forbidding Western frontier and the people who lived within these scenes. They still peer beyond the page, across the centuries, and into our eyes today.

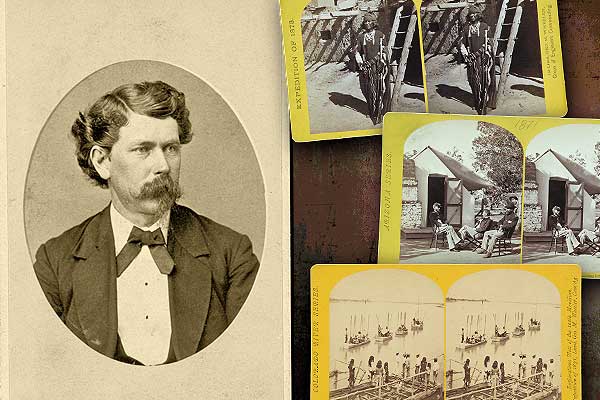

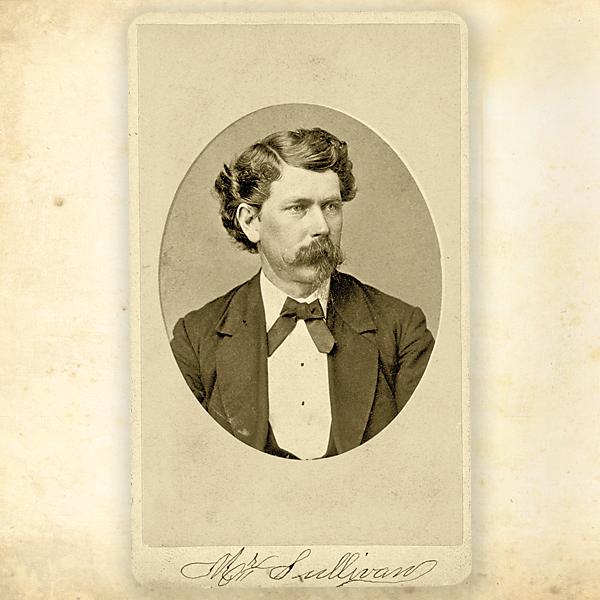

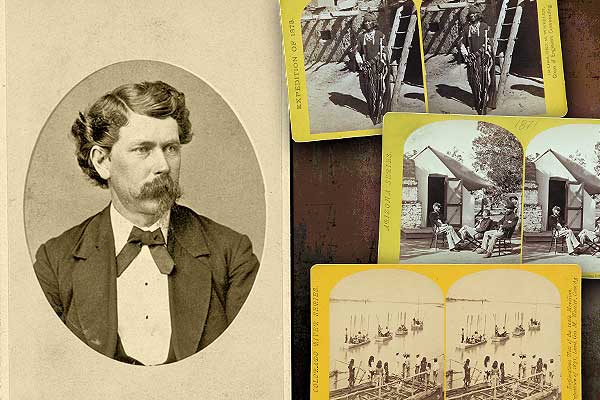

For Timothy H. O’Sullivan, born in Ireland in 1840, life was always going to be hard and unforgiving. Like so many of their countrymen, the family abandoned the ancestral homeland and crossed the north Atlantic on one of the “death ships,” fleeing the writhing famine of the 1840s for hopeful shores in America. Years later, O’Sullivan would claim Staten Island as his place of origin and that he had served six months in the Union Army, both of which are thought to be chosen embellishments, but reflective of a period when status was important and the Irish were an oft-despised immigrant minority.

He was fortunate to meet neighbor and noted photographer Mathew Brady and at the age of 16 was working for him in his New York City studio. In a few years, as the Civil War began, he was transferred to Brady’s Washington, D.C., gallery under staff photographer (and Scottish immigrant) Alexander Gardner. One of his first field expeditions, as part of “Brady’s Photographic Corps,” was to the Battle of Bull Run in Manassas, Virginia, on July 21, 1861. The 21 year old was nearly killed by an exploding rebel shell from field artillery, destroying his camera.

O’Sullivan survived the war, photographing the destruction for four years. His most famous wartime photograph, “Harvest of Death,” (July 4, 1863), showed the dead freshly collapsed on Gettysburg farmland. His large-format and chemically coated glass plates left crystal-clear and psychologically indelible images that will forever chill those peering into our nation’s past.

The bombardment ended; the War was over. There was no returning to a portrait studio.

O’Sullivan’s lust for adventure was now met by joining government-sponsored explorations. He took on the hardships of an 1867-69 geological survey of the 40th Parallel, exploring the area between the Rockies and Sierra Nevada Mountains. In 1870, he even traveled to Panama with a survey team to research a future canal across the isthmus.

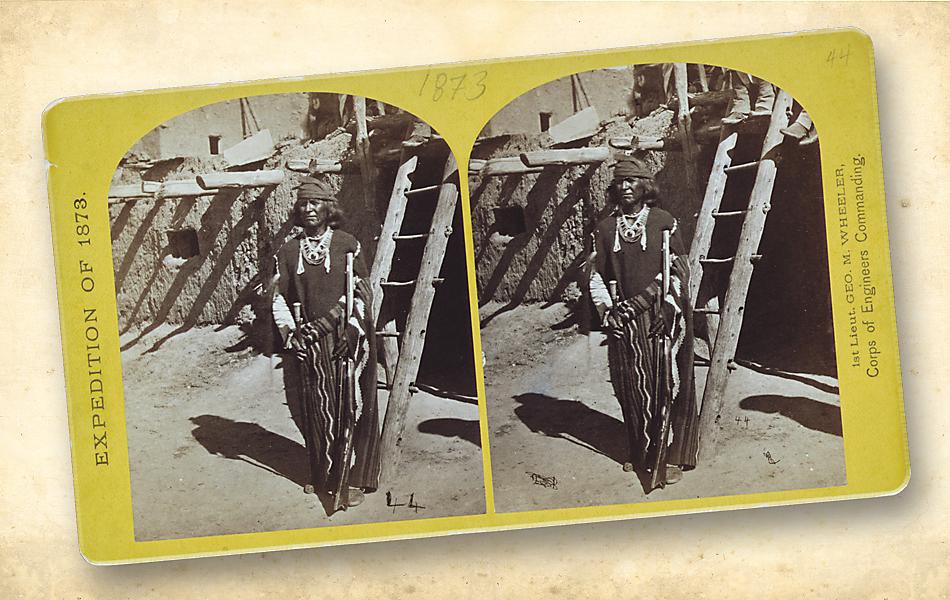

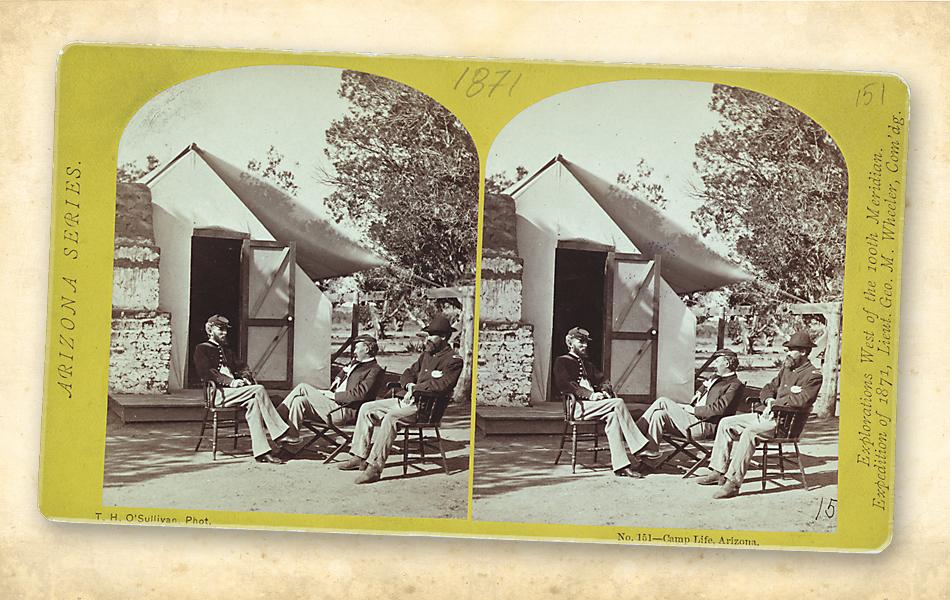

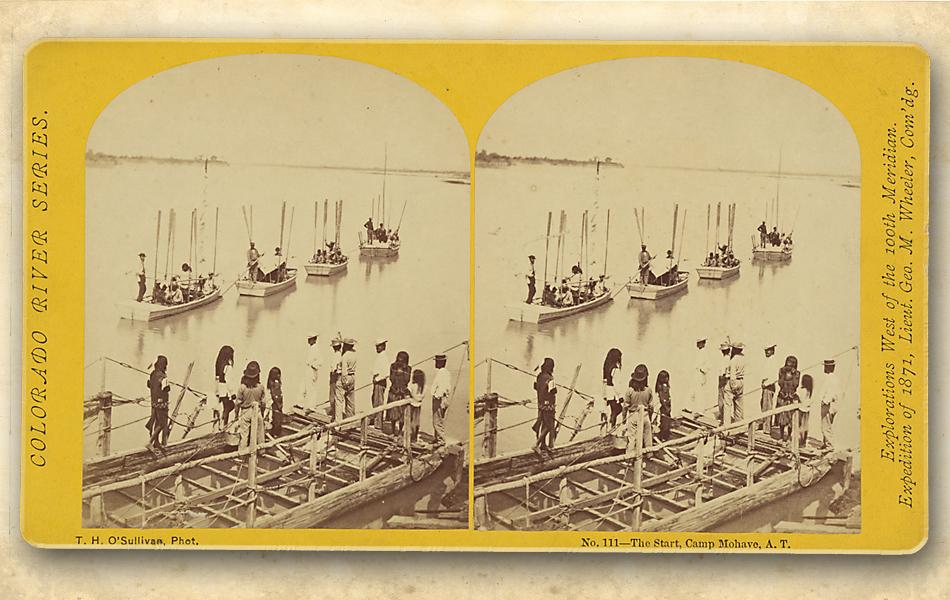

In 1871, he was on the Lt. George Wheeler Southwestern Geological Expedition, including a harrowing journey up the Colorado River, where many of his photographic plates were lost and the crew members almost starved after their rations went into the river in a boating accident. Sullivan’s images of the canyon lands, pueblos and the Southwestern Indian tribes they met along the way are timeless and a strong precursor to Edward Curtis’s famed ethnological study, The North American Indian.

He spent his last years as official photographer for the U.S. Geological Survey and the Treasury Department. His legendary Irish luck ended in 1876, when he buried his only child, a stillborn son, and watched his wife, Laura Virginia Pywell, succumb to tuberculosis in October 1881 as she stayed with her family, without him. He, too, contracted the lung disease and died three months later at his parents’ home in January 1882.

Tom Augherton is an Arizona-based freelance writer. Do you know about an unsung character of the Old West whose story we should share here? Send the details to stuart@twmag.com, and be sure to include high-resolution historical photos.

Photo Gallery

– all Photos courtesy Library of Congress –