He was supposed to be taking just a little trip to Sonora, Texas, on a cool April night in 1901. He planned to check out the bank, map the best routes out of town—and buy some grain for the horses.

But for outlaw Will Carver, shopping was a killer.

The tale of how Carver shopped until he dropped is told in Jeffrey Burton’s remarkable new book, The Deadliest Outlaws, the most comprehensive look at the Ketchum Gang (and the most thorough account of Carver’s death). The outfit—which included Black Jack Tom Ketchum and his brother Sam, Elzy (or Elza) Lay, Dave Atkins and Will Carver—wreaked havoc in the southwest during the late 1890s and early 1900s. The boys also associated with Butch Cassidy’s Wild Bunch.

By 1901, the Ketchum Gang was kaput. Sam was dead. Black Jack was waiting to be fitted for a hemp collar. Lay was in prison. And Atkins … well, he’d gotten the heck out of Dodge and made his way to South Africa where he worked as a gun for hire in the Boer War.

Carver rode with Cassidy’s boys—in fact, he was included in the famous Fort Worth Five photograph of Butch, the Sundance Kid, Harvey Logan (Kid Curry) and Ben Kilpatrick, which was taken months before his visit to Sonora. Butch and Sundance took off for South America in February 1901, while Carver continued on the outlaw trail with Kid Curry and Ben Kilpatrick, along with Ben’s little brother George.

The idea of robbing the Sonora bank was bold—or stupid, depending on your point of view. Carver and the Kilpatricks were well known native sons of the Lone Star state. The lawmen also knew what they looked like, thanks to that Fort Worth picture. That didn’t stop the outlaws; they planned to hit the bank on April 3.

On the evening of April 2, the group left their camp outside Sonora to case the town and get some oats for the horses. George Kilpatrick was a relative novice to outlawry, and he’d never been to Sonora. Carver decided to give him the grand tour, while Ben and Kid Curry cooled their heels in another part of town.

The outlaws didn’t realize the danger that faced them. A few days earlier, the crew had stolen some cattle to make steaks. Town folks were on the lookout for the rustlers. To make matters worse, Kid Curry had murdered a neighbor of the Kilpatricks back in March, so the alarm was out on that case too.

What’s a citizen to think of some strangers, riding up and down the streets after dark, taking good looks at the bank? Not good. A few good citizens apprised Sheriff Lije Briant that two suspicious men had entered the Owens Bakery.

Having once been shot during a confrontation with bad guys, the sheriff took no chances. He rounded up several men and headed for the store.

Just after 9 p.m., the group entered with guns drawn and ordered Carver and George to throw up their hands.

George froze, unsure of what to do. He never got out his weapon.

Carver, tying up a bag of oats, went for his gun, ready to shoot. He might have been able to put up a good fight—he was a deadly shot—but his pistol caught in his suspenders (note to self: buy belt on next shopping trip).

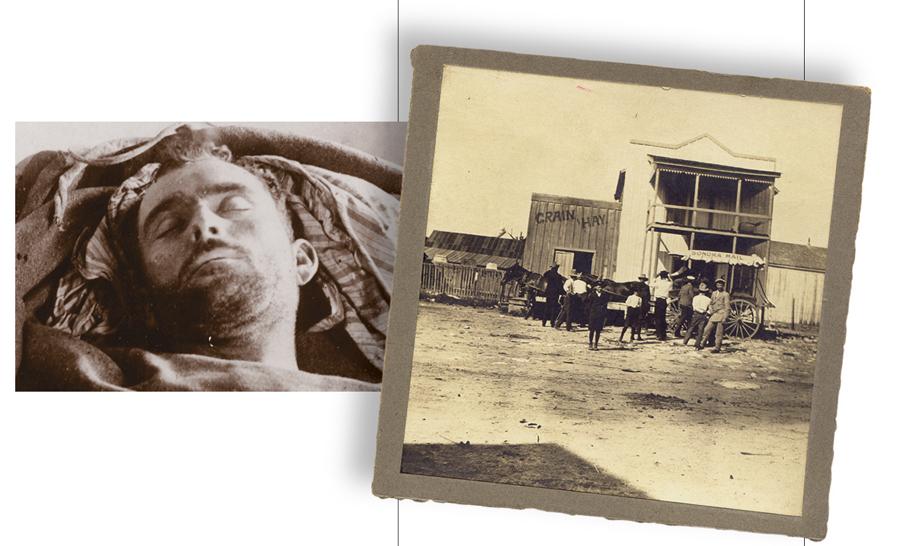

The officers opened fire and kept firing until both men stopped moving. They hit Carver seven times; George, five. The officers took the defeated outlaws to the courthouse, where they stretched out on the floor.

Carver died a couple of hours later. George surprised the doctors and survived his wounds (and avoided trial since nobody could prove he intended to rob the bank). As for their compatriots, Kid Curry and George’s brother Ben, they rode out of town when the gunfire started. They knew better than to get involved.

The town sold off Carver’s belongings—including his guns, horse and saddle—to pay for his funeral and burial in the Sonora cemetery. A few months later, his sister put a stone over his grave; it read, simply, “April 2, 1901.”

Maybe it should have read, “No refunds, no returns.”

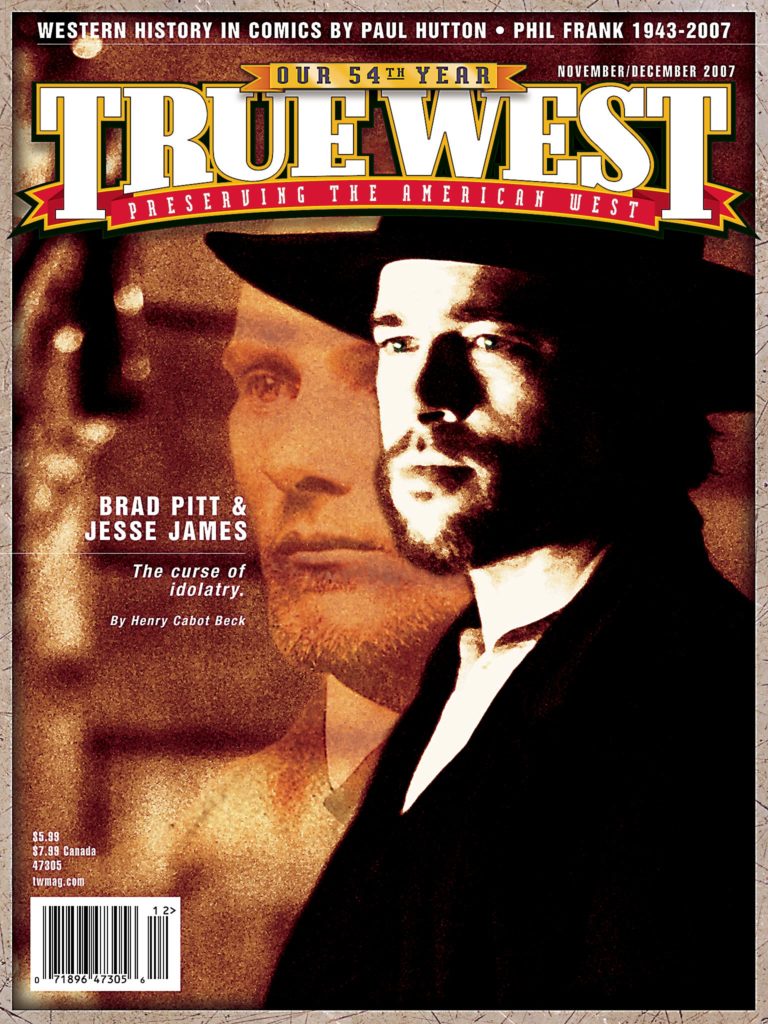

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Sutton County Historical Society –