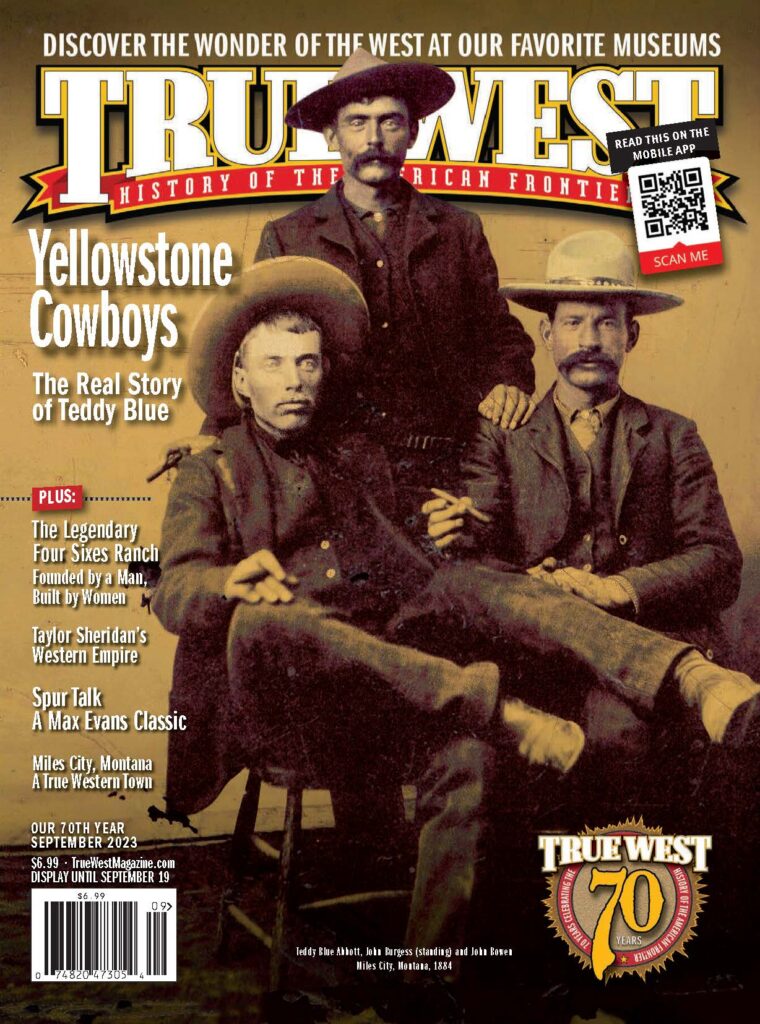

Travel the Rocky Mountain West to discover the truth about the legendary mountain man.

If he had to do it over, there’s a chance Hugh Glass would never have followed the Missouri River across South Dakota once, let alone returned.

Since this is True West, I should add this preface: everything in this story is true. Perhaps. Well, kinda. At least it is mountain man-true…you know, part of it might be a tall tale, or a windy, or a yarn, but the truth is in there somewhere. The story is 200 years old and has had lots of embellishments along the way, beginning within days of pivotal events.

In 1822, William Ashley and Andrew Henry ran an advertisement in a St. Louis newspaper calling for 100 enterprising young men to ascend the Missouri River and engage in the fur trade. Before long the fur traders headed upriver, building Fort Henry at the confluence of the Yellowstone River with the Missouri. Ashley then returned to St. Louis to recruit more men including James Clymer, William Sublette, Thomas Fitzpatrick and Hugh Glass.

Up the Missouri River

The trip upriver in 1823 was a grueling start as the men used ropes to haul—or poles to force—keelboats against the current, enroute to Fort Henry some 2,000 river miles upstream. They were just north of the confluence of the Grand River with the Missouri near the present border between North and South Dakota, in late May when they anchored the keelboats near a large Arikara village.

Ashley entered the village, successfully trading guns and ammunition for some horses. He then put Jedediah Smith and Hugh Glass in charge of the horse herd. The intent was for them to drive the horses to Fort Henry, while others in the party continued their journey by boat.

Everything changed the following day, June 1, when Arikara warriors launched an attack. It was short, but deadly. Less than an hour after the battle began it was over. Around a dozen of Ashley’s men were dead and several more were wounded, including Hugh Glass, who was shot in the leg.

Glass, with others who were wounded, and some of Ashley’s other men retreated to St. Louis. In August 1823, Glass had recovered enough that he again joined men working for Ashley and Henry. With six pack horses they set out across South Dakota intending to find an overland route to the mountain country where they could engage in the fur trade.

Against All Odds

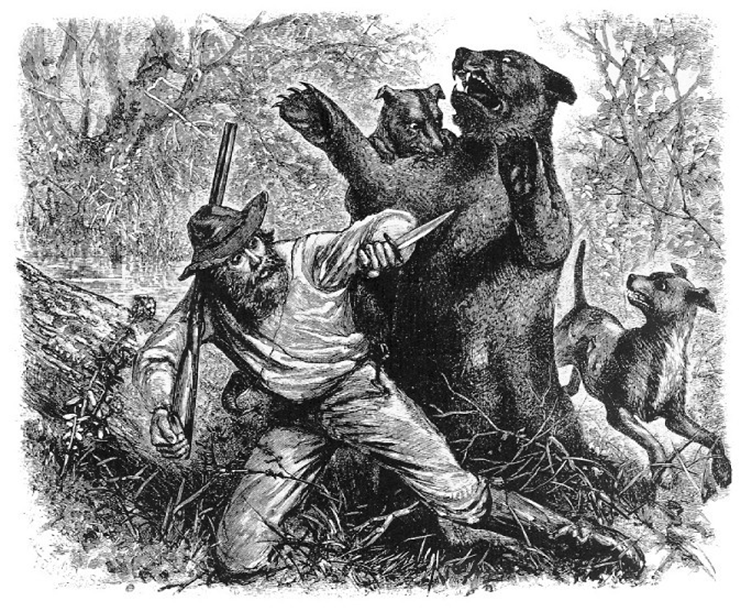

Once again along the Grand River, in the area near today’s Lemmon and Shadehill, South Dakota, Glass was ahead of the others looking for game when he stirred up a grizzly bear. The bear immediately attacked Glass, badly mauling him before some of his companions reached the scene and killed the bear. Expected to die from his injuries, Glass was left behind with two men—John Fitzgerald and a younger man listed in some accounts of the incident as “Bridges.” He is generally thought to be a young and then inexperienced Jim Bridger.

Fitzgerald and Bridges stuck around five days. Then, certain Glass had little time left to live and concerned for their own safety as well as a desire to reunite with the other trappers, they left Glass and took his tools of the trade: gun, knife and fire-making kit.

But Glass roused himself, and with nothing to help him survive, he started crawling toward Fort Kiowa, more than 250 miles from where he was injured. Coming upon a wolf kill of a buffalo calf, he waited until the carnivores

left, and then he devoured the remaining meat. He took other nourishment from the prairie he struggled across, having already learned enough about mountain man survival to find edible berries and roots.

His companions had abandoned him, but near the Missouri River Glass encountered some friendly Lakotas. From them he obtained a hide boat that he used to travel downstream to the area of Fort Kiowa near present-day Chamberlain, South Dakota, in mid-October. Still hurt and weak, Glass was also madder than hell.

After a period of recovery, he retraced his path, and finally in December he made it to Henry’s Fort on the upper Missouri near the confluence with the Yellowstone River. There, he expected to find Fitzgerald and the young man who had abandoned him. By the time he reached the site, Henry’s first trading fort had been abandoned and a second Henry post was built upstream on the Yellowstone, so Glass went there and learned Fitzgerald was no longer with Henry but had returned to Fort Atkinson, where he joined the military.

The younger man who had abandoned Glass was at the upstream Fort Henry site but whether there was any direct confrontation by Glass is uncertain. This story of redemption—according to most of the accounts—shows that Glass’s anger was more direct-ed at the older Fitzgerald than the younger “Bridges/Bridger,” whom

he forgave for the abandonment.

Glass ultimately re-turned to Fort Atkinson. When he learned of Fitzgerald’s position with the military, he abandoned his retaliatory grudge.

The Man and the Legend

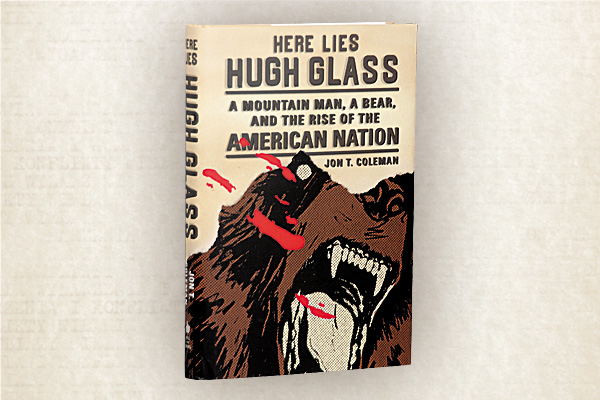

This tale of Glass and the battle with the grizzly followed by his epic crawl/walk/float across much of South Dakota has drawn attention since at least 1826 and became the story thread for articles, books—mostly novels but some purported to be nonfiction—and more recently the film The Revenant starring Leonardo DiCaprio.

The bicentennial of his early adventures in South Dakota—and the attack by old mama griz—takes place August 22-28 at the Hugh Glass Rendezvous in Shadehill/Lemmon, South Dakota. There will be black powder shooting, hawk throwing, primitive archery and no doubt some tall-tale telling.

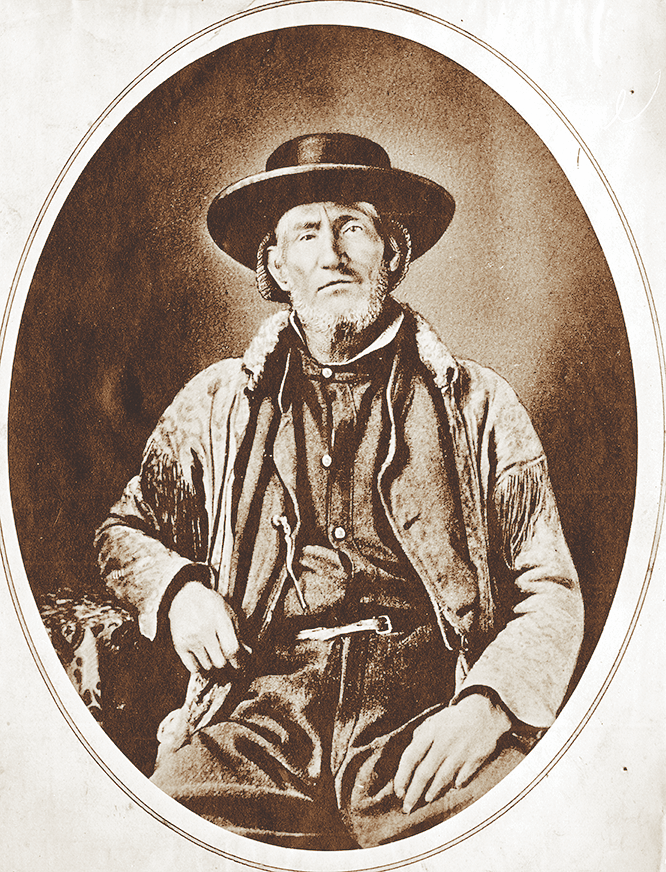

Glass is one of the most recognized of the mountain men because of the grizzly bear attack, but he was never as adept in the fur trade as some of the men who were contemporaries. Sublette, Fitzpatrick, Jedediah Smith and Jim Bridger all made bigger names for themselves in the trade and have left those names on places across the region. Glass himself ultimately left the northern plains and moved to Santa Fe, terminus of the Santa Fe Trail that had been pioneered by William Becknell in 1821. The scarred mountain man likely did some trapping along the Gila River and farther north near Taos.

There are accounts that put him back in the Rockies attending the summer rendezvous that took place on the Blacks Fork of the Green River for the first time in 1825, and then annually at locations from Bear River to the Upper Green River at Horse Creek, where seven of the mountain gatherings occurred. Learn more about those mountain rendezvous and the men who both knew and abandoned Glass at the Museum of the Mountain Man in Pinedale, which has one exhibit devoted to the Hugh Glass story and The Revenant—complete with a grizzly bear specimen. One other artifact on display at the museum is a gun Jim Bridger once owned.

Glass ultimately returned to the northern plains, spent some time at Fort Union Trading Post, which had replaced the first Fort Henry and is now a National Historic Site. He was killed by Arikara fighters in 1833, not far from the confluence of the Bighorn River with the Yellowstone.

A Wide Spot in the Road

Museum of the Fur Trade

With its collection ranging from fur traps, guns and other gear, the Museum of the Fur Trade is an outstanding site to visit and learn more about the mountain fur trade. The museum houses the most comprehensive collection of artifacts from the fur trade anywhere. Equally impressive is the collection of Plains Indian items ranging from war weapons to moccasins and other clothing items. Located just east of Chadron, Nebraska, the site is the location of the 1837 trading post James Bordeaux established for the American Fur Company. The site is on the National Register of Historic Places. furtrade.org

Good Eats & Sleeps

Good Grub: Al’s Oasis, Oacoma, SD; Mauricio’s Taco Shop, LaJunta, CO; Cattlemen’s Club Steakhouse, Pierre, SD; Bobcat Bite, Santa Fe, NM; Wind River Brewing Co., Pinedale, WY

Good Lodging: Dakota Lodge, Lemmon, SD; LaFonda on the Plaza, Santa Fe, NM; Chamberlain Inn, Pinedale, WY