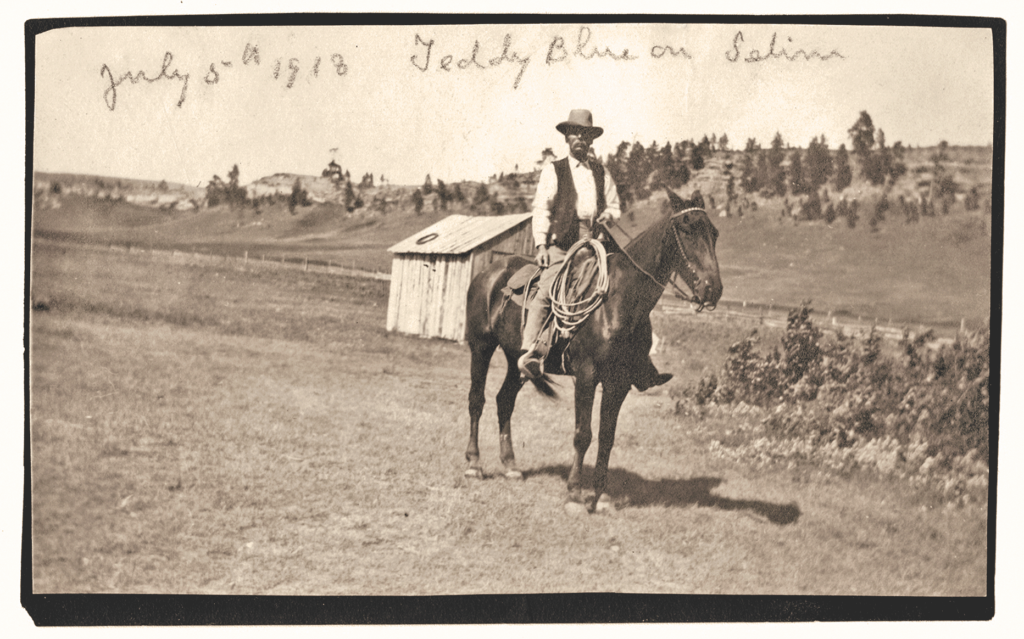

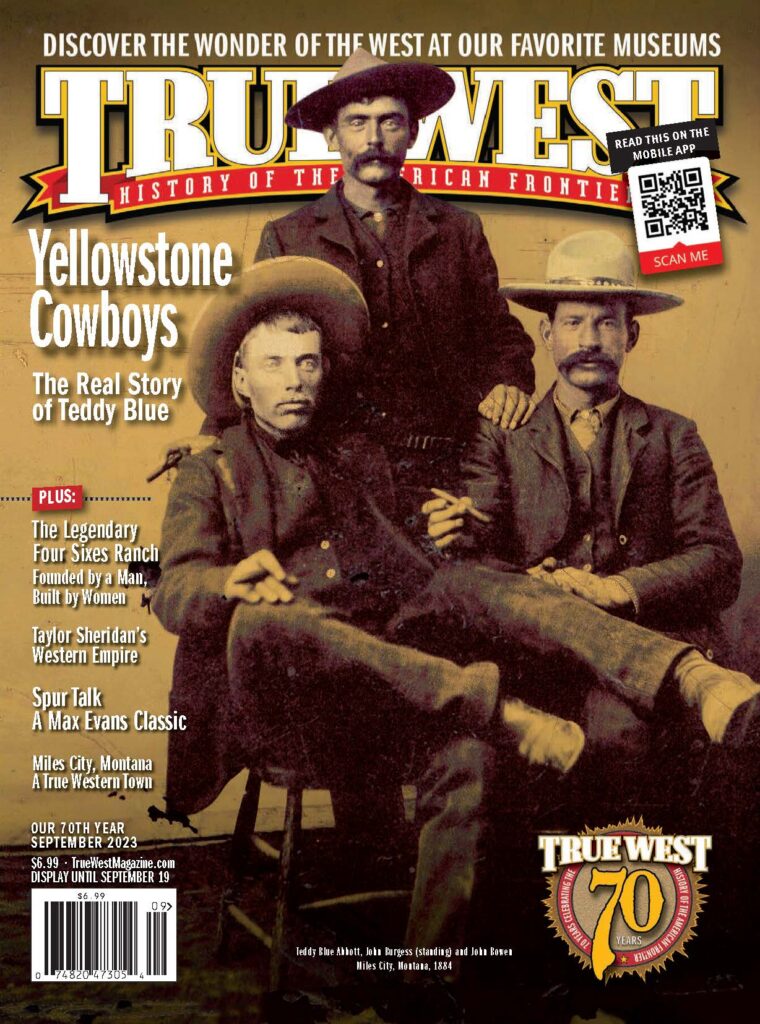

The real story of Teddy Blue and how he became Montana’s greatest cowboy.

“We all got well lit up and went to a hot show on Blake Street,” wrote Teddy Blue Abbott. “The play I think was called ‘Poor Nell,’ anyway, a burglar beats his wife to death on the stage. After he had knocked her down, he took hold of her hair and beat her head on the floor, and every time he struck her head he would stamp his foot. It sounded like her head hitting the floor, but it wasn’t her head at all. I was sober enough to know that. But some of them weren’t. Bill Roden, one of the cowboys, had went to sleep but the noise woke him up, and the first thing he saw was the man beating the woman’s head on the floor. We sat right in front, and he gave one jump onto the stage and busted the fellow on the head with his six-gun before he remembered where he was. The woman got up and began to cuss him, all hell broke loose, somebody pulled Bill off the stage, they called the police, the boys shot out the lights and everybody broke their necks getting away from there. They all run to Bailey’s corral where the horses were and got away before the police knew who to arrest. I made a sneak down the alley to Frank’s place, got what few dollars I had and left town on foot.”

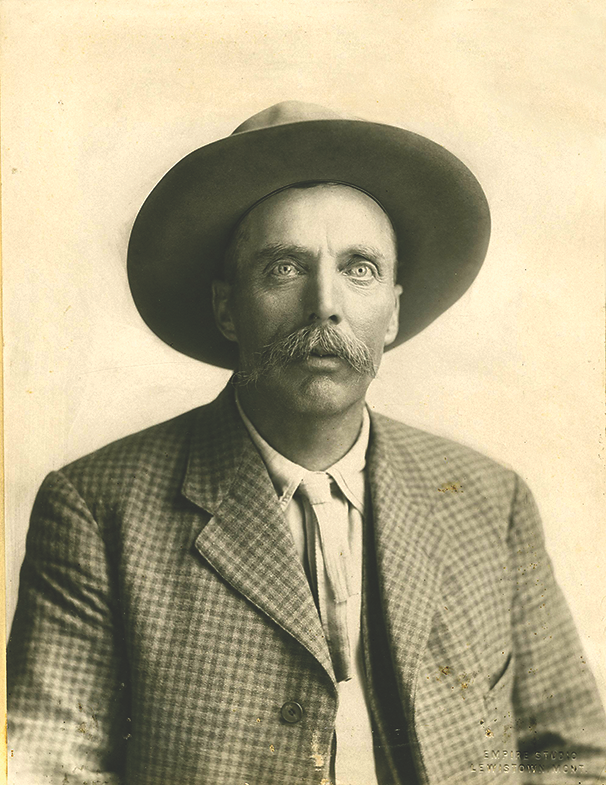

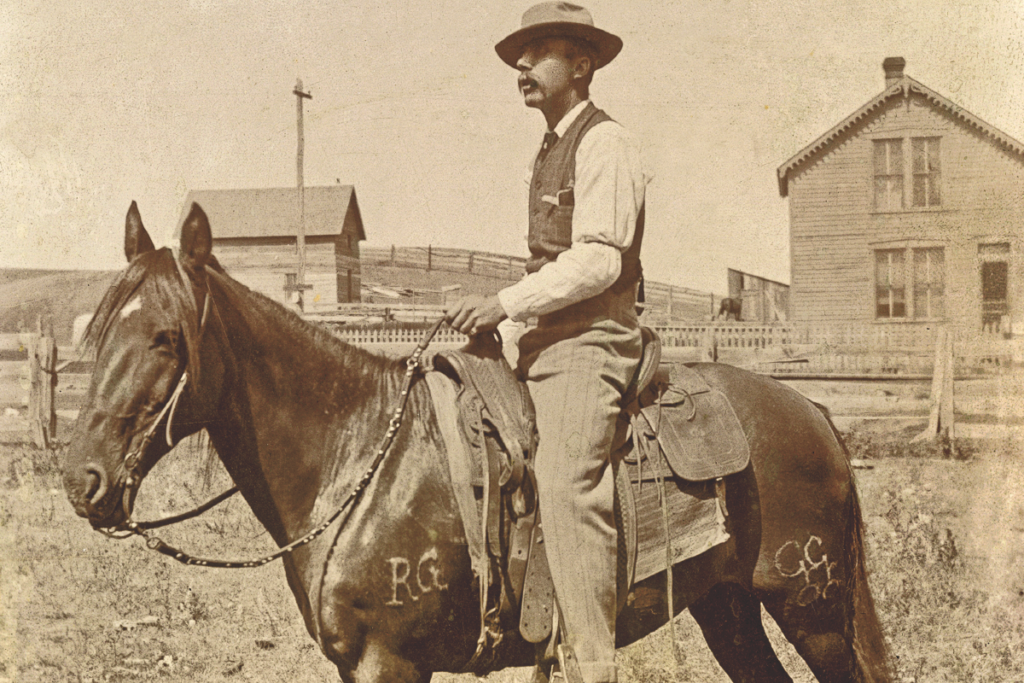

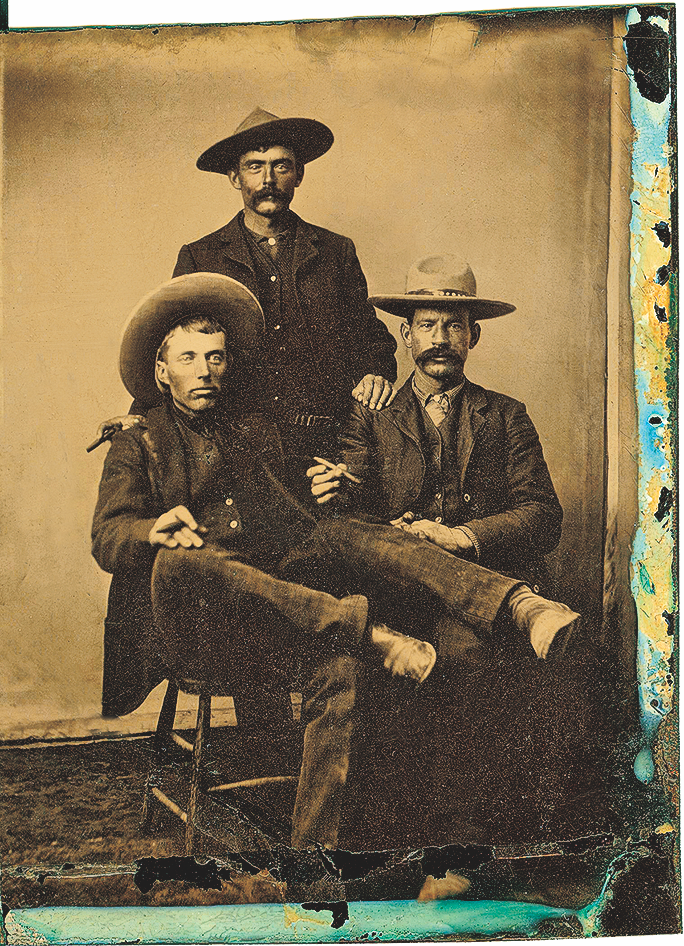

Arguably Montana’s most famous cowboy was Teddy Blue Abbott. Standing just five feet, eight inches, with ethereal blue eyes and a sense of humor and wit equaling that of his good friend, artist Charlie Russell, Teddy Blue Abbott’s short career as a cowboy bracketed the glory days of the herder who trailed cattle fearlessly from Texas to Montana. Full of life and happy-go-lucky, he could never sit still for long, singing, telling stories and melding into the untamed world of central Montana. His early years were filled with raucous, wild and dangerous days and nights of letting off steam with a devil-may-care attitude. The young Abbott also had a tough-guy reputation as a fighter. He lived the philosophy of work hard and play harder.

English Born, Western Bred

Edward Charles “Teddy Blue” Abbott (1860–1939) was born in Cranwich Hall in Cranwich County of Norfolk, England. His father was well educated, possibly at Cambridge. The young man related that he was considered a gentleman tenant farmer, who employed 20 or 40 men. But Ted’s father went broke, and his grandfather forced him to emigrate with his family to America in 1871. They settled outside of Lincoln, Nebraska. Young Abbott’s father traveled to Texas with a man named Colonel Enzie to buy 1,200 cows. Ten-year-old Abbott was brought along to help wrangle horses and, in that manner, became enchanted with the Texas cowboy. The Texas Trail had been in existence for three or four years, and already it was big business. Teddy Blue later noted that in 1871, 600,000 cattle were driven up the trail to Lincoln, Nebraska. Different outfits trailed the cattle north following the Chisholm Trail nearly to Abilene, Kansas, and eventually settled near Lincoln on the north end of the Texas Trail. There were no ranches north of that point, only Indians and buffalo. At Lincoln they grazed the cattle and shipped them east on the Burlington and Missouri River Railroad.

Abbott’s father purchased steers from the trail herds every year until 1878. Young Abbott tended his father’s cattle from 1871 to 1878, and claimed it made a cowboy out of him. Abbott’s father turned to farming, which did not fit well into his son’s lifestyle, so he left, moving west. He began working for the Olive Brothers, who had a tough “gun outfit” reputation in western Nebraska. Abbott fit in well. He gradually began working as a “top hand” for several cow outfits. “In 80 I went to Colorado & New Mexico worked for Hall Bros. Cross L in 81.”

He also worked for John Chisum on the Pecos River for a while. This time frame coincided with the Lincoln County troubles, where one was either on the side of Billy the Kid or against him. The Kid had also worked with Chisum the year before, falling out over a money dispute. He stated that as a rule cowpunchers didn’t have any use for the Kid. Personally, Abbott didn’t feel it was his fight and held no bias for or against the notorious outlaw. He later wrote in his book that he got out of there “muy pronto.”

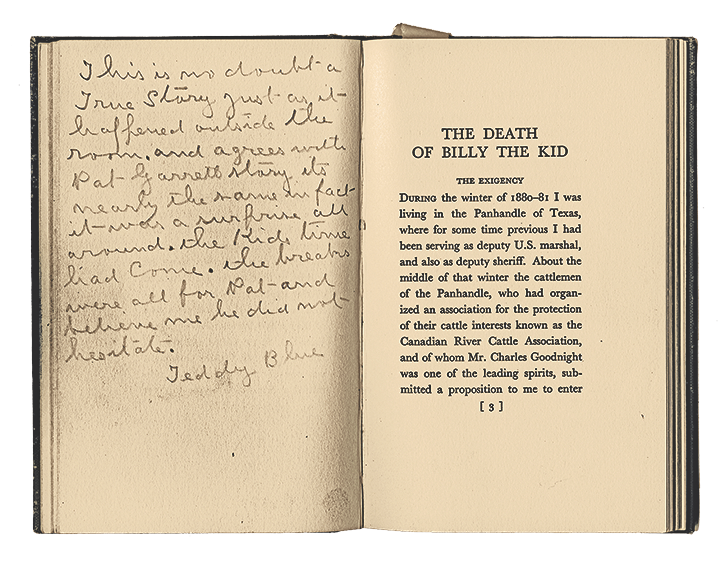

Years later, in 1935, Teddy Blue was gifted a book written by John W. Poe, titled The Death of Billy the Kid. Reading the book prompted him to reminisce about Billy the Kid, and he annotated his copy of the book with his trademark pencil. When the book described how Billy the Kid was shot in a darkened bedroom at Maxwell’s dwelling house by Pat Garrett in 1881, Teddy Blue wrote,

“This is no doubt a True story Just as it happened outside the room. and agrees with Pat Garrett’s story its nearly the same in fact it was a surprise all around. The Kids time had come. the breaks were all for Pat—and believe me he did not hesitate. Teddy Blue.”

When the Kid entered Maxwell’s bedroom to talk, Teddy Blue’s penciled annotation continued, “[T]he reason the Kid did not shoot was because he did not know who they was but Pat knew him.”

In April 1883, Abbott hired out with the FUF outfit in San Antonio and made his first trip up the trail from Texas, driving longhorn cattle destined for the Yellowstone River, the ultimate destination for cowpunchers in the 1880s.

“We turned loose on Armell’s Creek, south of Forsyth,” recalled Abbott. “In the Spring of 1884 I went to work for T. J. Bryan, the first president of the Montana Stock Association. That is how I attended the first meeting. I have attended about 40 in all. I first met Theodore Roosevelt in 1884, on Powder River, on the fall round-up. He was a good fellow. He made a hit with us at Powderville when he told Mason, who ran the stage and saloon, to give us all we could drink—and we sure done ’er! Those old time cow men—what a big hearted bunch they were! They always played the game straight up to win. No one ever knew them to copper a bet.”

Abbott described the cowboy during the range days as good-natured, loyal to his outfit, wild, and brave, who feared only two things: a decent woman and being set afoot without a horse to ride.

The biggest years on the Texas trail occurred in 1883 and 1884. Many of the cowboys trailing from the Texas trail settled east of the Rocky Mountains in Montana, Wyoming, Colorado and New Mexico, and in western Dakota Territory, before the farmers later ran them out. Writing in 1930, Teddy Blue expounded, “The first herds were tough outfits compared with what they were toward the last. I do not believe anyone really knows how many million cattle went up the trail from Texas bound for the northern ranges, but they certainly were the salvation of Texas as the money from them made Texas what it is today—the second best state in the Union (Montana always first), even if it did go for Hoover.”

A Glimpse of Miles City

Abbott’s arrival in Miles City coincided with the zenith of the “cowboy capital.” Texas trail herds first approached Miles City in 1880, followed by the Northern Pacific Railroad in the fall of 1881. The hamlet developed next to an army post, initially called the Tongue River Cantonment (Fort Keogh). In 1877, after the fort was established, Col. Miles ordered the “coffee coolers” off the post grounds. This assortment of hustlers, storekeepers and saloon denizens moved just east across the Tongue River to the southern banks of the Yellowstone River to set up the “old town” of Miles City.

The population rose to 600 people by early 1880, with 72 ranches along the Tongue River. Miles City was becoming the central hub of a cattle and livestock empire. A year earlier, Robert Strahorn estimated the number of cattle in Montana Territory at 250,000. The official assessor’s figures set the number of cattle inhabiting Montana Territory two years later at 287,210, sheep at 362,776, and an astounding 67,802 horses.

The human population doubled the following year, and 42 saloons served 1,000 bottles of beer a day. The monthly intake of whiskey was an astonishing 1,300 gallons. All the saloons provided wide-open gambling replete with faro, stud, roulette tables and blackjack. Attractive girls were available for adult companionship, with hurdy-gurdy houses for the dancers.

In 1884, Teddy Blue Abbott experienced Miles City firsthand when working as a rep for the N Bar. His back had been injured in an accident on a roundup when his horse reared and fell on him. He was given a pass to Miles City to recuperate at the expense of the company.

Teddy Blue’s honest description of the social environment painted a candid picture of Miles City as a wild frontier town.

“The buffalo hunters didn’t wash, and looked like animals,” Abbott recalled. “They dressed in strong, heavy, warm clothes and never changed them. You could see three or four of them walk up to a bar, reach down inside their clothes and see who could catch the first louse for the drinks. They were lousy and proud of it.

“The cowboy was a totally different class from these other fellows on the frontier. We was the salt of the earth, anyway in our own estimation, and we had the pride that went with it. That was why Miles City changed so much after the trail herds got there; even the women changed. Because buffalo hunters and that kind of people would sleep with women that cowpunchers wouldn’t even look at, and it was on our account that they started bringing in girls from eastern cities, young girls and pretty ones.”

With the arrival of law and order on the streets of Miles City, Teddy Blue began to mature. As with many young men, his priorities changed when he fell in love. For Teddy Blue that transformed his life.

A Few Days Short of 50 Years: A Love Story

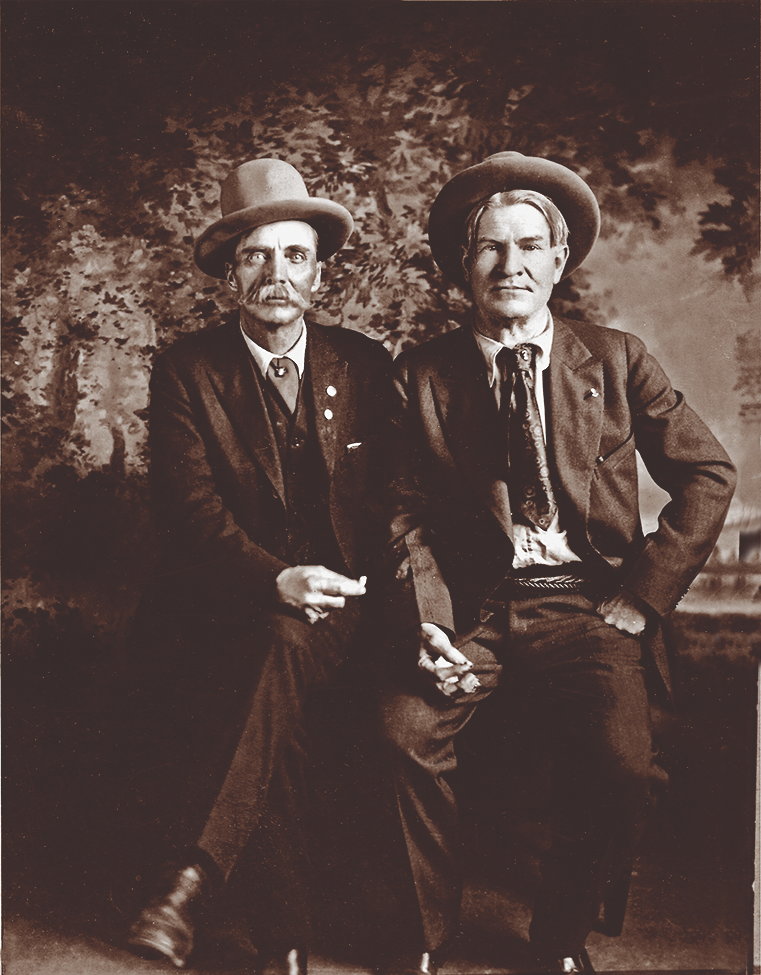

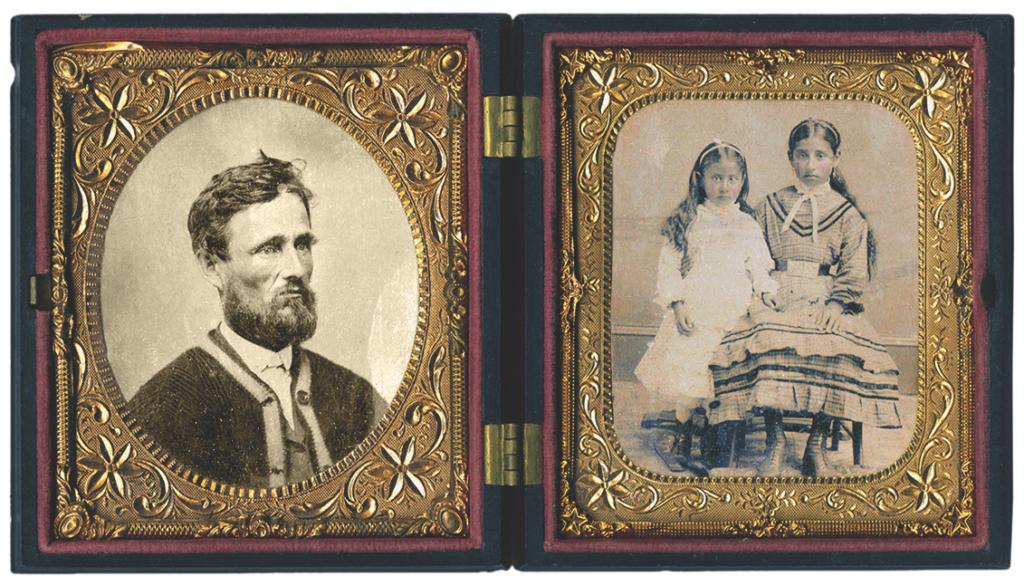

The spirited 24-year-old Teddy Blue Abbott had an ulterior motive for wanting to work for the DHS. While working for John Burgess during the winter of 1884–85 at the mouth of the Musselshell River, a grub line rider came into camp and spread the news that pretty girls had been spotted at the DHS Ranch 75 miles away. Respectable single ladies, according to Teddy Blue, were practically nonexistent in that part of the territory.

Granville Stuart, the manager of the outfit, had announced he would give 500 head of cattle to the man who would marry his oldest daughter, Katie. Born in a tent at Virginia City on October 6, 1863, Katie was now 22 years old, and her parents thought a significant dowry would lure a capable, responsible suitor. From the same source, Blue heard that the younger daughter, 15-year-old Mary, was the best-looking. Mary was born on February 2, 1870, in an old log cabin built by Madame Rene Poitier and Peter Martin in Deer Lodge.

Sight unseen, Teddy Blue picked the pretty young one to court. Conveniently, in the spring of 1886, Burgess fired Teddy Blue for not digging postholes in the hard ground with a “grub hoe.” Teddy Blue hired on with the DHS, and when Burgess attempted to rehire him, he refused, saying Granville Stuart’s outfit had wonderful grub, including canned tomatoes and peaches along with dried apples and prunes.

He probably muttered under his breath that Stuart’s outfit also had a sweet, smart, and articulate young lady named Mary Stuart.

The correspondence between Teddy Blue and Mary Stuart is a window into 19th-century puppy love on the upper Missouri River. In the spring of 1887, Blue was riding horseback with Mary and told her that he regretted not buying new clothes, but he had drank up all his money. Mary told him that she would never be with a man who “throwed his money away on whiskey.” Then and there he decided to stop drinking and chewing tobacco and began saving his money. The roughshod, kind-hearted cowboy had met his match; he wholeheartedly had fallen in love, and in doing so, performed a complete turnabout.

Granville and and his wife, Awbonnie, were disciplined, strict parents with their girls. Awbonnie wanted Katie to be married first. That didn’t stop Teddy from secretly courting the younger daughter. In August 1887, Mary and Teddy Blue, on a raspberry-picking outing, separated from the ever watchful eyes of Awbonnie and sealed a commitment to each other by etching their initials, TA—MS, on an 1848 seated Liberty half dollar, with the date of “Aug 7, 1887,” etched on the coin’s reverse. Over the years, the meaningful betrothal coin became worn because Teddy Blue carried it in his pocket during their nearly 50-year marriage. Teddy once said that he had fallen in love with “the first good woman” he had ever met.

On September 29, 1889, Teddy Blue’s wild bachelor days came to an end. Transformed and reformed, Teddy became a respectable and popular member of the community. The Abbotts settled on the 3 Deuce Ranch, near Gilt Edge, Montana, with a handful of horses and cows and $250. They eventually produced nine children of their own. It certainly was a love story for the ages, as their marriage lasted nearly 50 years, ended only by Teddy Blue’s death.

clothing his children.

Drought and Depression

Back in 1889, once he and Mary settled on the 3 Deuce Ranch, they slowly prospered, and in the early 1900s he was worth $40,000, a sizable sum of money at the time. In the 1920s, the rainfall ceased and the beautiful grasslands transformed into a dust bowl. The lingering drought thrust a third of the banks into failure, triggering the rapid departure of thousands of homesteaders. Teddy Blue remained and sold most of his cattle to climb out of debt. As he waited patiently for the ranching industry to revive, the Great Depression occurred, creating a further financial calamity for many Americans.

During the drought years beginning in 1919, Abbott began to get serious about writing stories about his adventurous life, as he was searching for ways to make a living. The possibility of cashing in on his writing was a novelty on the northern Plains. Russell had accomplished the feat with his art. But Charlie had Nancy to promote his journey, and Mary Stuart Abbott was no Nancy. She had a pack of children to care for and appeared comfortable staying in the area. Occasionally Teddy Blue sold a few stories to newspapers and periodicals; however, the public’s taste tilted toward sensationalized, bloodthirsty stories of violence and bluster, not necessarily toward authenticity.

Teddy Blue’s first article, published in the Fergus County Argus holiday edition in 1919, was titled “Christmas at Fort Maginnis 1885.” The story was written as a reminiscence of the early-day settlers and ranchers on the numerous creeks surrounding Lewistown. It is unknown whether he was paid for the article.

He sold an article to the Montana Newspaper Association titled “Some of the Old Bunch I met down at Billings.” He complained to De Yong that the editor, William Cheeley, had sensationalized the story to suit the public. He also successfully sold “Early Trail Days” to The Producer, a publication of the American Livestock Association, in 1930.

Teddy Blue turned to others for advice on publishing his writings including Charlie Russell, Will Rogers, Will James and Joe De Yong.

Like many Americans during the depths of the Great Depression, Teddy Blue had fallen into debt. In order to feed his family, he admitted to Nancy Russell, Charlie’s wife, he had resorted to selling five letters she had written to him for $10, which combined with “enough old books to buy 6 months grub.” Previously Teddy Blue had furnished two letters to Nancy for inclusion in Good Medicine. In the same letter written to Nancy he had been offered $45 for his favorite letter. He turned it down because he wanted $100.

Nancy Russell inquired about any Charlie-related stories from his rowdy days in the Judith country during the 1880s. She was writing a biographical memoir on Charlie and desired authentic stories of when he “was mixed up with a big-hearted, gambling, drinking bunch of cowboys whom he always loved and from where he got so much inspiration for his pictures.” Nancy was anxious to have his old friends, especially Teddy Blue, relate stories that placed Russell in a good light.

Little came from Teddy’s attempts to sell his life stories. His debts increased, and during the Depression the cattle business was not recovering quickly enough. Abbott persisted; he sold a story to the Billings Gazette for $3 in 1934, but they rejected another story, citing the lack of gunplay.

A small newspaper, the Nashua Independent, in January 1935 printed one of his articles on an early cowboy, J. D. O’Malley, and Teddy Blue also wrote an article on Granville Stuart’s son, Charles, for an unspecified newspaper. In 1937, the Cattleman magazine in Fort Worth published his story on Texas cattleman John Blocker, the “King of the Texas Trail.”

We Pointed Them North

Life isn’t always fair, and sadly, Teddy Blue was unable to enjoy his published triumph We Pointed Them North, re-

leased in September 1938. It was conceivably the grandest event of his life. His ghostwriter Helena Huntington Smith once proclaimed Teddy Blue a genius: “If this isn’t the best book ever written about cowboys, then I’ve never read one.”

On April 8, 1939, his youngest daughter penned a letter: “Our Teddy Blue passed away yesterday morning at 8:45. He had been sick only a week with asthma pneumonia. It was so terrible as he just got his book last Monday and was really to[o] sick to look at it much. I am so glad he got to see it before he went.”

Those words resonate to this day, and Teddy Blue must have known to some degree his historical contribution to the cowboy and cattlemen of that era. His daughter wrote that despite being too sick to enjoy the book, it seemed as if he had accomplished his life’s dream and was just through. Five hundred people attended the funeral, and as he wished, he was buried with his boots on and his hat placed in the casket. Helena Huntington Smith gave him a well-deserved tribute when she concluded in her introduction: “In his chapter on Granville Stuart he says magnificently: ‘Granville Stuart was the history of Montana.’ Well, Teddy Blue is the history of the cattle trail and the open range.”