The day Bill McDonald rode over the hill leading the Appaloosa, Slim and I were repairing the corrals. Slim was running Pete Coleman’s little ranch about three miles south of Cow Springs, New Mexico. I was just a snotty-nosed, freckle-faced kid at the time.

Bill rode up and said, “Howdy, Fellers.”

It made me feel right proud to be included among the “fellers.” I think Slim and I both sensed something wrong when Bill first spoke.

“How’s things goin’, Bill?” Slim asked.

“Not so good. Little Feller, here, throwed my boy,” he said, “I think his leg’s busted.”

“The hell you say.”

“The third time this week,” Bill said. “Can’t understand it. The wife has gone into Santa Fe for the Doc. It’s pretty bad, and we was afraid to move him till we got aholt of the Doc.”

The big Appaloosa stood there as gentle as a milk cow. A man couldn’t imagine he’d buck at all. According to his size, he was sure named funny. Bill’s boy, Herod, started calling him Little Feller when he was a colt and the name stuck. He was especially big for this part of the country where the main horse used was the small Spanish mustang. Little Feller must’ve weighed around eleven fifty and was powerfully muscled. I knew that in the early days the Appaloosa was prized by Indian chieftains, not only for his unusual markings, but because of his toughness. “Slim,” Bill said, “I’ve got to get on back but I sure as all hell wish you’d give this old pony a workin’ over.”

Slim said, “All right, Bill, I’ll see what I can do,’’ and reached for the Appaloosa’s rein.

Slim kept looking Little Feller over and Bill rode off, and I heard him mumbling to himself. Then he said aloud, “Can’t figger it out. That horse is four years old and he never bucked a jump all the time Herod was breaking him. But,’’ he added, “I’ve seen ’em that way before. If you don’t take it out of ’em quick, you’ve got an outlawed horse on your hands.”

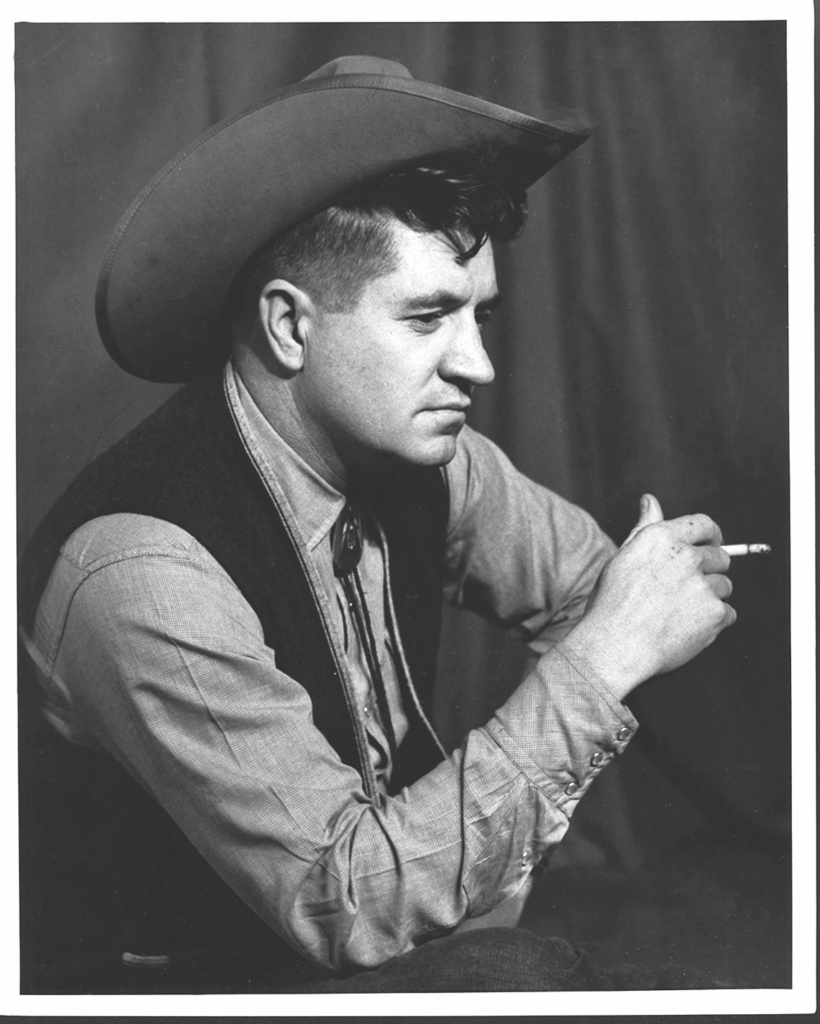

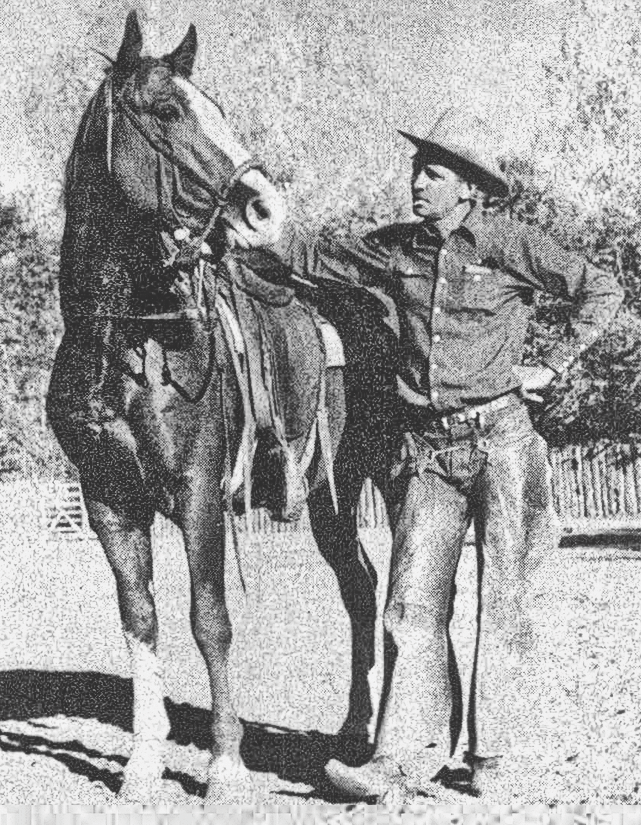

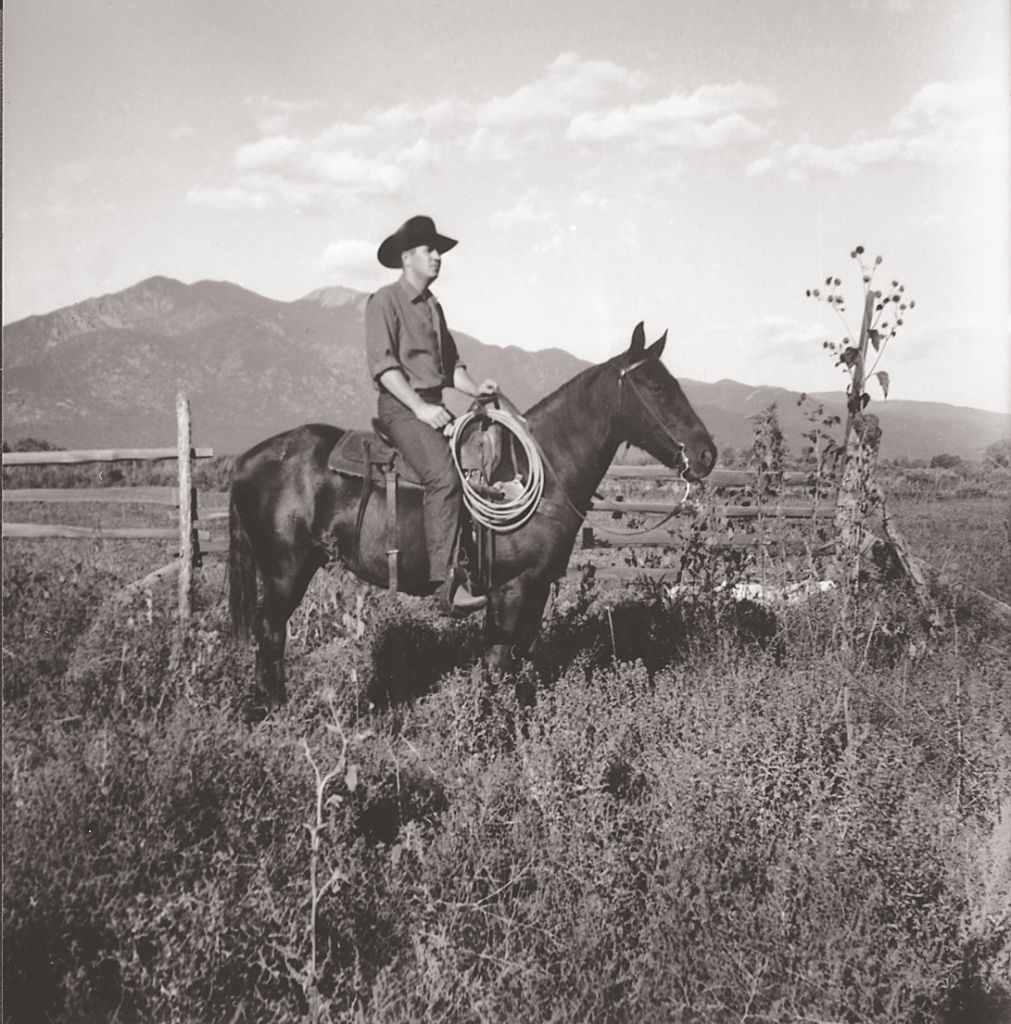

Slim was one of the best horse-breakers in this part of the country. You could hardly find an outfit around that didn’t have a horse or two he’d tamed.

He led the Appaloosa into the corral we had been repairing. He felt around on Little Feller’s back to be sure there weren’t any stickers or sore spots. There weren’t. Little Feller didn’t even flinch when Slim threw the saddle on

his back.

Then Slim stepped up on him, sure of himself, but careful just the same. He eased the pony into a trot, then gradually worked him into more speed. Around and around the corral they went. He watched closely and all the time his right hand was on the saddle horn. Slim wasn’t a rodeo rider; he used that horn for what it was put on a saddle for. The sweat broke out on Little Feller, but he didn’t buck at all; in fact, he hadn’t even humped up.

When Slim stepped off, he said, “Saddle up Red. We’re goin’ for a ride.”

Red was a sorry old sorrel horse that wasn’t fit for anything except to keep around the house to wrangle the other horses on. I saddled him up.

Slim swung an arm at a deep arroyo that ran all the way to a long mesa about two miles off. He said, “Now, if Little Feller heads for that arroyo, you run in front of him and beat him across the face with your hat—anything to keep him from jumpin’ in that thing.”

Little Feller fox-trotted along easy like. I rode right by his side, between him and the arroyo. We covered a quarter of a mile without seeing anything of interest but a lizard that raced about looking for shade.

Then it happened. A ragged patch of air was expelled from Little Feller’s insides. He snorted and went from me about four long, ground-pounding jumps, then sucked back. I knew then this was t e way he had thrown Herod McDonald. But Slim was ready and though I could see the strain in his face and arms he stayed put.

Little Feller got mad then. He bellered like a bull buffalo and ran nearly over the top of the sorrel and me. I was scared half to death but managed to spur old Red in front of him, cutting away from the arroyo.

Every time Little Feller went up, he bellered. Every time his feet hit, the ground shook and he left deep tracks in the earth. And every time Slim’s head was snapped back and all his bones absorbed the shock, but he was still on.

He hadn’t a chance to spur much at first, but now he had the rhythm of the horse, so he bogged it to Little Feller. A small patch of hair went into the wind every time one of Slim’s heavy spurs hit. Then, just as suddenly as Little Feller had started, he quit.

I rode up, proud of Slim, and said, “You’ve got him whipped. I bet he don’t never buck again.”

“Hell,” Slim said, “He’s just gettin’ warmed up.”

Slim was sure right. We had ridden maybe another hundred yards when the old devil jumped into a dead run. Just as he reached his peak of speed, he bogged his head and went straight up. I could hear the whoomp of his belly and guts as he came down. Slim’s hat went off. I knew then things were tough. I’d seen Slim pull that hat right down over his ears when we left the corral.

Little Feller bucked straight ahead with those high power-driven jumps. Then he bucked back again, but in a different direction than before. Slim almost lost a stirrup but managed to pull back with the Appaloosa. Again Little Feller stopped as suddenly as he’d started.

Slim yelled for me to get his hat. He stepped off to tighten the cinch. A lot of lard had already melted under that horse’s tough hide, and I could see quite a bit of daylight between his belly and the leather flank strap.

Slim didn’t waste any time. He jerked his hat down even farther on his head and climbed back aboard. I couldn’t make myself believe that Little Feller could go on with it any longer, but I didn’t say anything. I knew Slim wasn’t in the best of spirit at the time.

Little Feller stumbled along until he reared right straight up in the air. If Slim hadn’t yelled like a wild Comanche and whopped him over the head with his open hand, I figure Little Feller would have fallen back on top of him.

When the horse’s front feet hit dirt again, Slim had his hand back on the saddle horn. Don’t think for one minute that he was ashamed of “pullin’ leather.” A working cowboy doesn’t like to walk home when he’s miles out in the pastures. He learns damn quick to stay on anyway he can.

Little Feller started kicking back with his hind legs, just as his front dug into the ground. A back-kicker is one of the meanest buckers in the world to ride. While Slim’s body would follow the forward motion, the back kick would catch him right in the middle of it and wrench him hard the other way. Slim’s face was white as death. I could see the leaders in his neck standing out and the muscles knotted where his jaws were clamped together. Then, just as we rounded the mesa point, I saw the blood stream from Slim’s nose. I wanted, worse than anything else in the world, to yell to him to quit. But I had been taught to keep my mouth shut on such matters, so 1 didn’t say a word.

Little Feller got within six inches of a fence that Slim had told me to watch. He turned back, more from Slim’s heavy spur in his neck than he did from Red and me. When he stopped this time, I could see that he was mighty tired. He stood with his head down, legs apart and his lather-covered sides worked in and out as his lungs pulled for more air. Slim sat up on him, as if he didn’t know that the blood had circled around the corners of his mouth and was oozing down under his chin. His shirt was sprayed with red splatters.

I couldn’t imagine, even then, that a horse could buck that far and that hard or that a cowboy could stay on his back that long and live—but there they were. At the time, I was sure of only one thing—I knew Slim was going to get killed. It had boiled down to some sort of personal battle between the man and the horse.

Without saying a word, Slim reached out and raked the rowels of his spurs from high in the neck right back to the flanks. They left a track all the way. Little Feller answered with a sideways jump. He bucked slowly, but just as hard as he had in the beginning. Slim never stopped the music of his spurs. They seemed to me as if they were separate from his tired body.

We were at a gate when this session ended. I could see now that blood was coming out of the corners of Slim’s mouth, as well as his nose. They stood there a long time. I started to get down to open the gate, but Slim said, “No, I’ll get it.” I really don’t know why he wanted to open the gate, unless it was just to show that Appaloosa that he could still walk.

He wobbled on his boot heels and Little Feller moved stiff-legged through the gate. His shoulders were marked a lot from the spurring. Slim got back on, but barely, his leg didn’t quite swing over far enough. If Little Feller had been fresh he would have lost his rider right there—but he wasn’t fresh.

Slim spoke, and I could tell by the rasp of his voice that his throat was mighty dry. “This is it, you son-of-a-bitch.” But in his cussin’ I could hear respect.

The Appaloosa made only two more high, hard, honest jumps. I could hear his guts beat at his sides. Slim winced away from the jar when he hit. Then he struck him with the spurs once. He swung his legs out wide and dug the steel in where the horse’s neck joined his shoulders. It popped almost like a gun, only not as sharp. The horse stopped again. There was no need to go any further. We turned around and came back through the same gate, only this time I opened it.

That night and for several, there in the bed-rolls, I could hear Slim moan, roll and talk to Little Feller. The next day Slim had me ride Little Feller back over to McDonald’s. When I asked him if it would be all right, he said, “Why, sure.”

He was right, but I wonder how he knew. Maybe Little Feller had told him that day over by the gate that he’d never buck again. One thing I know, if the horse did say anything, Slim sure would have understood, because he’s the kind that talks horse language.