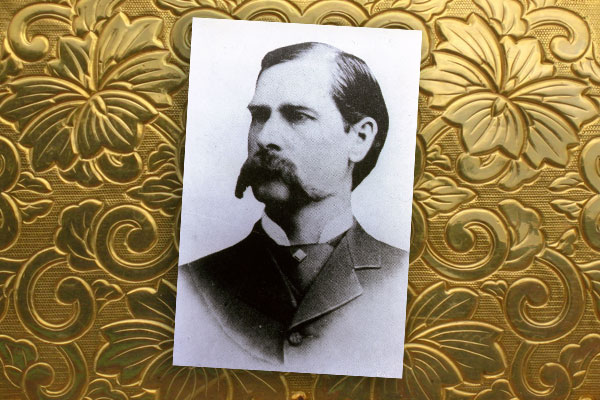

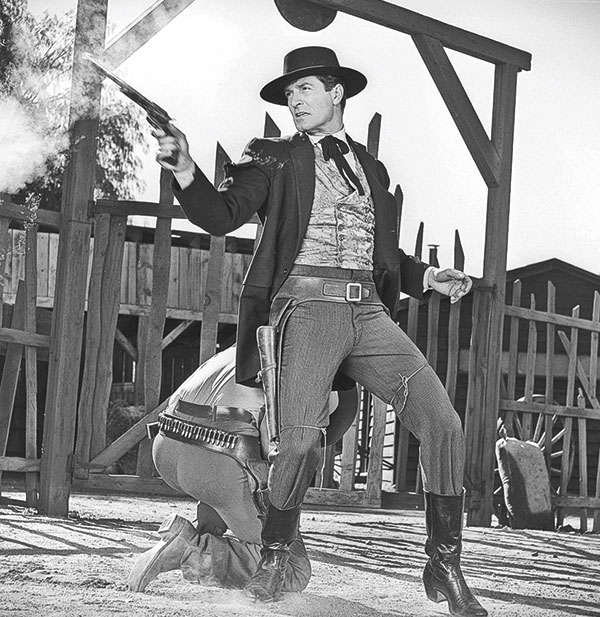

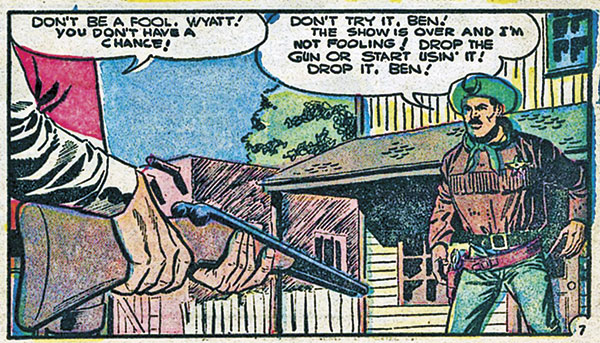

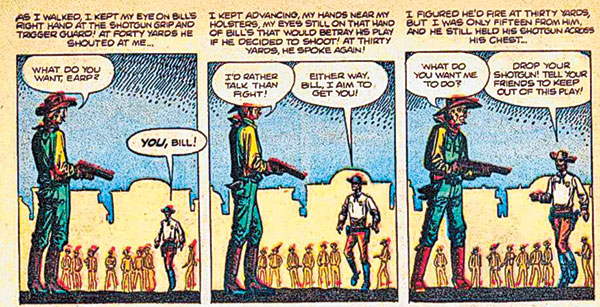

— All illustrations courtesy State Library of New South Wales, Australia unless otherwise noted; Wyatt Earp photo True West Archives —

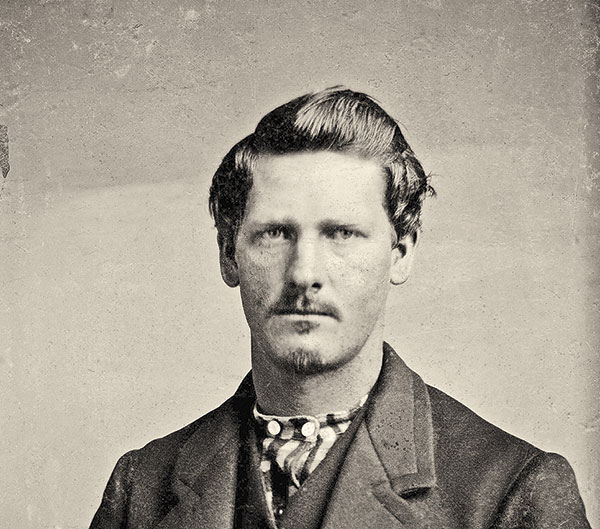

Among the many questionable incidents people often repeat about Wyatt Earp’s life story, few reveal the duplicity of his biographer as much as the tale of Wyatt’s 1873 showdown with Ben Thompson in Ellsworth, Kansas.

Letters between Stuart N. Lake and a Hollywood producer show the legend makers of print and film collaborating to create a fictional character who both men insisted matched the real man.

The Ellsworth Incident

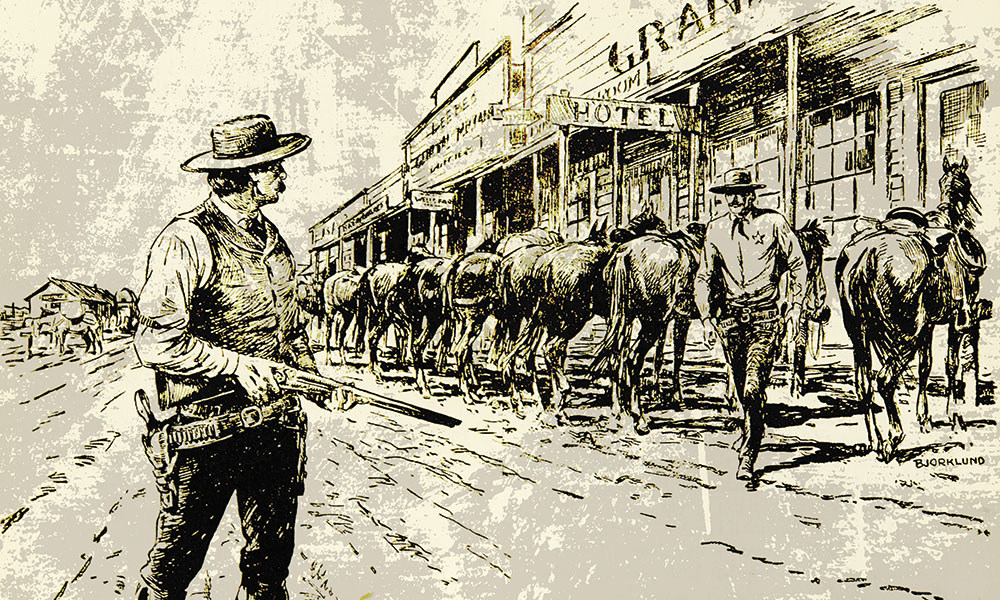

Stuart N. Lake first told the story of the Ellsworth incident in a 1930 Saturday Evening Post article. A wandering buffalo hunter searching for opportunities in the cattle business, Wyatt landed in Ellsworth on August 18, 1873, where he responded to a dangerous standoff after the killing of Sheriff Chauncey B. Whitney. Bill Thompson had shot Whitney and was allowed to ride out of town, while his brother Ben held off any pursuers with a shotgun. The remaining Ellsworth peace officers were too cowed to challenge Ben until Wyatt volunteered to arrest him, with the aid of two borrowed six-shooters and a sheriff’s badge. Striding fearlessly across the street, Wyatt ignored the “hundred or more half drunken cowboys” who backed Ben and intimidated Ben into surrendering. When offered a permanent position on the police force by the mayor, Wyatt contemptuously refused due to the court’s release of Ben on a $25 fine.

— Courtesy Boot Hill Museum of Dodge City, Kansas —

The problem with this story is that it has not been proven. The only contemporary description of the incident appears in the August 21, 1873, issue of the Ellsworth Reporter, and Wyatt’s name is conspicuously absent. The newspaper story describes the shooting of Whitney and Mayor James Miller’s impatient discharge of the town’s cowardly police force, but it identifies Deputy Sheriff Ed Hogue as the only officer remaining to make arrests and the person who “received the arms of Ben Thompson.”

Lake’s source for his contradictory version of the event apparently came either from his own imagination or Wyatt. Evidence Wyatt may have told the story is contained in a 1928 letter he sent to Lake. Referring to a Texas gambler named George Peshaur, Wyatt wrote, “I had some little trouble with him in Ellsworth, at the time that I arrested Ben Thompson.”

Wyatt could have come up with his tall tale by reading the Ellsworth Reporter article. Wyatt enclosed a batch of unidentified newspaper clippings to Lake that year, and the Ellsworth story might have been among them.

Stuart Lake Stretches the Truth

Regardless if Lake made up the story or repeated what Wyatt told him, the biographer left clues that suggest he realized he had stretched the truth.

Lake embellished his Saturday Evening Post version of the Ellsworth incident by claiming “no more than a handful of the narrators of Earp history seem to have been aware” of the showdown, implying other accounts existed.

In 1931, when Lake published his book Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal, he doubled down on his claim of available historical evidence by quoting the Ellsworth Reporter text verbatim, but he intentionally left off the concluding sentence that identified Hogue as the man who received Thompson’s guns. Lake couldn’t resist bragging that no other historians had been aware of the Thompson showdown, as opposed to the “handful” he had admitted previously.

Both of his claims, however, set a trap to catch Lake in his lie by declaring the story’s roots could be independently verified.

In the decades following his publication of Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal, Lake grew to consider his Wyatt character as his personal intellectual property. He often sought payment from any print or film depictions of Wyatt that he claimed may have used material from his book, but he found that difficult for works that retold his version of the Ellsworth incident.

The only Western film based on a Wyatt Earp character to feature the heroic staredown with a Ben Thompson character was The Arizonian, filmed in 1935 from a script written by Dudley Nichols. The movie was released just a year after Frontier Marshal by Fox Studios, which had purchased the exclusive rights to Lake’s book.

Historian Paul Andrew Hutton has speculated that Lake passed on an opportunity to sue Nichols because the Earp biographer had claimed the Ellsworth incident to be part of the historical record. His conclusion is supported by Lake’s reluctance to litigate two decades later when the Thompson showdown came up again.

— Hugh O’Brian photo Courtesy ABC; postcard courtesy NBC —

ABC Defends Lake

In 1953, Hollywood producer Robert F. Sisk wrote to Lake asking about the television rights for Frontier Marshal. Recognizing an opportunity to boost book sales, Lake agreed to a contract, although Sisk rebuffed his additional demands for final script approval and recurring on-camera introductions to each episode.

Sisk allied with Louis F. Edelman as the executive producer for The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp, and the pair began to line up the sponsors, talent and network contracts necessary to make the show a reality. Sisk secured the talents of Frederick Hazlitt Brennan, a scriptwriter with many screenplays to his credit, but he also wanted Lake to provide stand-alone narratives for each half hour episode.

“I wait with real interest your rough on the first Earp story,” Sisk wrote to Lake in May 1954, “and the reason or rationale of his being a peace officer.”

In true Hollywood fashion, the producer added, “and work a dame in, if but slightly.”

Once filming got underway, a magazine article appeared that threatened to scuttle the entire project.

In the summer of 1955, Argosy magazine came out with an expose written by Edwin V. Burkholder titled, “The Truth about Wyatt Earp.” Filled with the usual anti-Earp screed of previous debunkers, Burkholder also gave a fascinating spin on the Ellsworth incident, which must have hit close to home for ABC, as the pilot was going to feature the Ellsworth showdown.

Burkholder reported Wyatt had actually participated in a con job by agreeing to publicly arrest Ben Thompson before the showdown. Wyatt was able to stare down the Texas gunman because he knew in advance Ben would not shoot.

Burkholder finished up his spurious retelling by mocking Lake’s version and definitively stating, “The court records name Earp as the arresting officer.”

Intentionally or not, Burkholder had touched on the one “fact” that Lake could never deny without admitting the bankruptcy of his own version.

One of the sponsors of the show, General Mills, expressed alarm about Burkholder’s story. Sisk demanded a detailed rebuttal from Lake. Instead of complying, the writer complained about his status for the show’s credits and urged the producers to just ignore the “silly” charges. Reminding Sisk, “if it were not for your Uncle Stuart, there would not be much of a series,” Lake insisted he be given story credit for the first episode in addition to the title of consultant.

“Certainly, no one can dispute the fact that the Ellsworth business, barring a couple of twists, is right out of the book,” he argued, a sideways admission that the Thompson showdown came from his imagination alone.

Curiously, in his urging of the producers to leave the Argosy story unanswered, Lake acknowledged that an 1884 account of the affair by Ben Thompson failed to mention Wyatt Earp, as if that omission somehow added to the proof of his own version.

Sisk was far from reassured by his petulant consultant. The problem with General Mills was serious enough that he was forced to answer the Burkholder story in the columns of Variety, assuring the entertainment industry that the record of Wyatt’s personal life was “impeccable.”

Lake’s Bold Bluff

Still seeking a credible statement from his consultant to back up his rebuttal, Sisk again pressed Lake for a response.

Lake wrote back about his ideas for manufacturing T-shirts and publishing a juvenile version of Frontier Marshal and a serialized Sunday newspaper comic strip. He again laughed off the Burkholder story.

Sisk began to lose patience by the end of July. He reminded Lake that he needed a specific denunciation of the Argosy article. Lake again stalled, angry about his reduced role in the production of the Ellsworth episode, which he thought he would be introducing himself.

— Illustrated by Robert Doremus / Courtesy Whitman Publishing —

“You sen[t] down a script for the pilot just before you started to shoot it,” he fumed, “When I came up a few days later I learned that it had been entirely rewritten, not only as to story but [also] including the introductory narration.”

After a lengthy complaint about being edged out of script approval, Lake grumbled that his response would be forthcoming. Another week passed before he addressed the issue, and in his letter, Lake spent most of his typewriter ribbon questioning the value of Argosy magazine in general and the questionable identity of Burkholder in particular. He suggested Sisk demand Argosy’s editors produce Burkholder in the flesh to document the article under oath. Lake smugly predicted Argosy would be unable to do so and bluffed, “I can document my biography of Wyatt Earp in every essential paragraph,” a bold claim for a book that failed to include a bibliography or even a single footnote.

As it turned out, the General Mills executives were mollified by Sisk’s response in Variety, and the pilot episode of The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp aired on ABC on September 6, 1955. The pilot opened with an enthusiastic narrator who assured viewers that the “stories they tell about him are doubly fabulous because they’re true!”

The Ellsworth story featured Hugh O’Brian’s Wyatt Earp bravely facing down a less-than-threatening Ben Thompson played by Denver Pyle. (Perhaps due to budget considerations, the supposed crowd of 100 backing Thompson was reduced to three.) The credits named Brennan for both the story and the script, a subtle indication of the growing strain between the producers and Lake.

The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp became a hit and enjoyed six years of particularly high viewer ratings, but Sisk and Edelman eventually refused to renew Lake’s contract. They also left him to challenge alone any histories of Wyatt that did not infringe on the show’s copyright.

In 1956, no less than six new children’s biographies of Wyatt appeared in bookstores, including one written by Lake. Although he challenged some of his competitors, he could not specifically claim their repetition of the Earp-Thompson showdown as plagiarism. By that time, he had ensured the Ellsworth incident be viewed as an established historical “fact.”

Professor Kim Allen Scott is the university archivist at Montana State University Library in Bozeman. He discovered the letters between Stuart Lake and Robert F. Sisk in a mislabeled file folder that was part of the Frederick Hazlitt Brennan papers at UCLA.