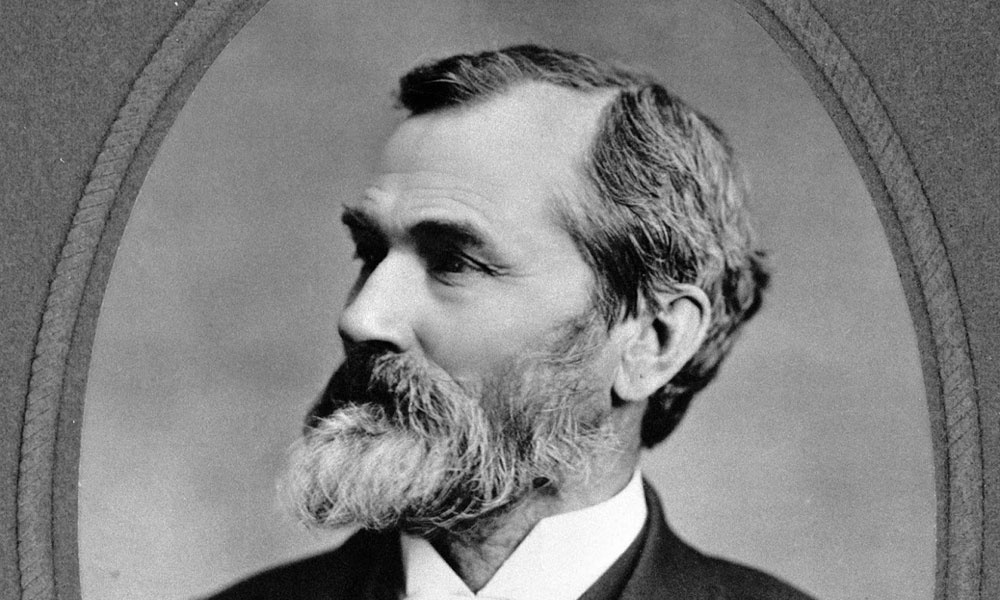

Ever wondered what kind of man would risk making a cattle drive from Texas to Montana and not even reach Virginia City until December? Turns out John B. Catlin answered that question back in 1912.

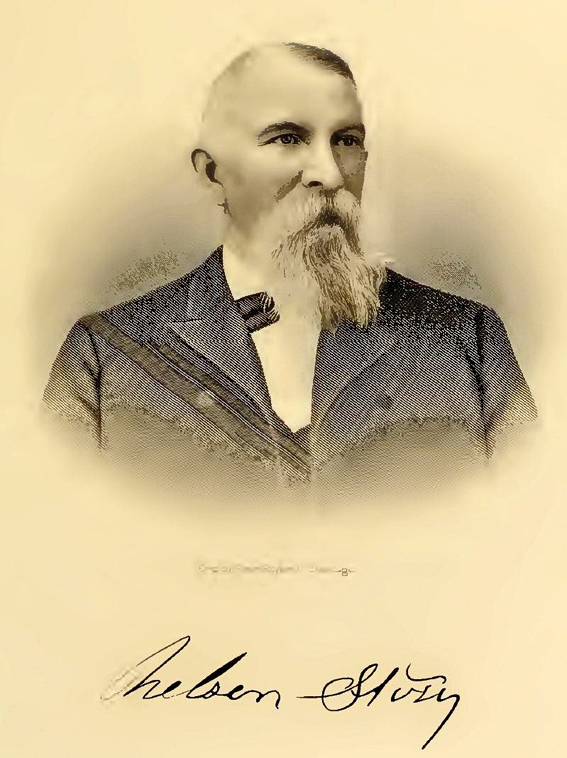

“Even after three years on the skirmish line in the Civil War, I had never seen a fighting man like Nelson Story,” wrote interviewer Arthur L. Stone. “He hunted a fight and when he found it he knew how to handle it. He never carried a rifle, but there were always two big navy revolvers on his hips. He was always splendidly mounted and would ride like the wind. He would say, ‘Come on boys,’ and ride away. Of course, we’d follow him—we’d have followed him to hell….”

So come on, boys and girls, let’s follow Nelson Story.

Eastern Born, Western Bound

Born in 1838 in Meigs County, Ohio, Story headed west in the late 1850s and by 1863 was in Montana, where his wife, Ellen, sold pies for $5 in gold dust. During his life he would be a schoolteacher, freight driver, miner, merchant, vigilante and the richest man in Bozeman. But he earned his place in history by leading one of the most remarkable cattle drives in Western history.

In 1866, Story arrived in Fort Worth, Texas. Or was it Dallas? Anyway, he had roughly $10,000 in greenbacks sewn into his coat. Or was it more? Whatever city and whatever the cash, he bought a herd of Texas that numbered 3,000. Or was it 1,000? It could have been only 600.

That’s one of the problems with sorting out the facts about this cattle drive. There’s really no definitive history. We don’t even know for sure the actual route Story took to Montana, and the Bozeman Trail has been described more as “a general direction” than an actual trail.

You certainly won’t find any agreement between Dallas and Fort Worth—on anything. Fort Worth is more cowtown and more Western (Sid Richardson Museum, National Cowgirl Museum and Hall of Fame). You can see cowboys drive longhorns at the historic stockyards, although they don’t go anywhere near the distance Story and his men and beef covered. Dallas is more cosmopolitan, more J.R. Ewing and JFK. There are cowboys and longhorns, but those are bronzes at Pioneer Plaza. That said, you can’t knock a city that claims it invented the frozen margarita in 1971—even if I prefer mine on the rocks.

Across the Red River

In any event, around April, Story pointed his cattle north.

At first, if you believe the legend, Story wasn’t thinking about feeding miners in Montana. He wanted to turn a meaty profit by driving a herd to Kansas City, Missouri. Or maybe he just wanted an excuse to chow down on K.C. barbecue.

Likely, the Story crew started out along the Shawnee Trail, crossing the Red River into present-day Oklahoma. That would have taken Story to Fort Gibson, where the reconstructed 1824 fort and several original buildings are worth seeing.

Perhaps Story followed the Neosho River to Kansas, where some say they went through Baxter Springs. But wouldn’t they have sold their herd there? More likely, if they’d stuck to the Neosho they would have reached Humboldt, a picturesque town founded in 1857 where today visitors should take the self-guided Civil War tour, check out the circa-1907 two-level bandstand and visit the Humboldt Historical Museum.

If you’ve read enough Kansas histories, you know that Kansans disliked Texas cattle herds because of “tick fever.” That’s likely why Story turned the herd west and why he was arrested in June in Greenwood County, taken to Eureka (Greenwood County Museum) and fined $75. That also might have soured Story on the idea of selling his beef in Kansas City.

After all, if a pie cost $5 in Montana gold camps, what would a Texas longhorn fetch? Forget K.C. barbecue. Story had decreed: Montana or Bust.

They crossed the Kansas River on a pontoon bridge at Topeka (Kansas Museum of History, Great Overland Station) and went to Leavenworth.

Letting the cattle graze, Story took several men into Leavenworth to celebrate Independence Day. Today, Western history buffs celebrate Leavenworth, where history lives. Take the city’s “wayside” tour, visit the First City Museum and don’t forget to see Fort Leavenworth. Yes, security’s strict—but I still got in—and the Frontier Army Museum is fantastic.

Story knew about the Indian conflict on the Bozeman Trail, so he outfitted his men with 30 breech-loading Remington rifles. He also bought 15 freight wagons, which he filled with groceries and merchandise to sell in Montana, and 150 head of oxen. They left for Montana on July 10.

Westward they went, along the Kansas River to Fort Riley near Manhattan (check out the U.S. Cavalry Museum), then likely turned north and followed the Big and Little Blue rivers into Nebraska. After that it was a simple drive of cattle, oxen and wagons along the Oregon Trail through Kearney (Fort Kearny State Historic Park), Gothenburg (Pony Express Station), North Platte (Buffalo Bill Ranch State Historical Park), Ogallala (Boot Hill) and into Julesburg, Colorado (Depot and Fort Sedgwick museums).

A Fight Across Wyoming

Turning along the North Platte River, they came to Fort Laramie, Wyoming, home of one of the best preserved old Army posts in the country. That’s where they picked up John B. Catlin and Steve Grover, who were taking a freight wagon to Bozeman and weren’t about to travel alone. It’s also where Army officials tried to halt Story because of Red Cloud’s War. Story didn’t listen.

Ten miles south of Fort Reno, Story got his first real taste of Lakota Indians. The Indians attacked, stampeded the herd and ran off with some cattle. In return, the Lakotas quickly got a taste of Nelson Story.

Catlin recalled: “…we didn’t lose a single head, we just followed those Indians into the badlands and took the cattle back.”

Outside of Sussex, you’ll find only a marker denoting Fort Reno’s existence. The fort was abandoned in 1868 and burned by victorious Indians. After all, Red Cloud wound up winning his war.

Leaving his wounded men at Fort Reno, Story pushed on to Fort Phil Kearny, where Colonel Henry Carrington stopped Story for the trail crew’s protection. Protection?

Carrington didn’t want civilian livestock grazing on Army grass, so “We were camped three miles from the post, so far that the soldiers could not have rendered assistance if we were attacked,” Catlin said. “…We just had to sit there and twiddle our thumbs.”

Story wasn’t much for thumb-twiddling.

After two weeks, Story asked his men to vote to stay or go. All but one voted to go. The dissenter was “arrested” and made to come along anyway. On the night of October 21, Story moved out—two months before Captain William Fetterman and 80 men were killed by Indians just over the ridge from Fort Phil Kearny.

Montana: The Promised Land

Story quickly realized that traveling by night and grazing the cattle—well-guarded, naturally—during the day was the way to travel. But don’t travel by night. The area is too scenic and full of history. You won’t want to miss it.

He pushed on across Wyoming to Fort C.F. Smith (part of Bighorn Canyon National Recreation Center), and then, after fording the Yellowstone River, along the Emigrant Trail. It was fairly easy for Story then, and it’s smooth traveling today. In Billings (Western Heritage Center) and Livingston (Yellowstone Gateway Museum), Story set up a ranch near present-day Emigrant, where the Story Cattle Co. & Outfitting remains in operation for hunting and vacation rentals.

Some cattle (we assume) and the freight wagons went on past Bozeman (Museum of the Rockies—but return to Bozeman when you’re done. He’s buried at Sunset Hills, a statue of him on horseback is at Lindley Park, and the mansion he built for his son in 1910 stands on Willson Avenue.

On December 9, 1866, Story’s amazing journey ended at the still wonderful, exciting and vibrant Virginia City.

I wonder if, to celebrate, he splurged on a $5 pie baked by his wife.

Johnny D. Boggs has dreamed about writing a novel about Nelson Story’s legendary cattle drive, but so far the only thing he has come up with is a title, which he isn’t sharing because it’s not that good anyway.