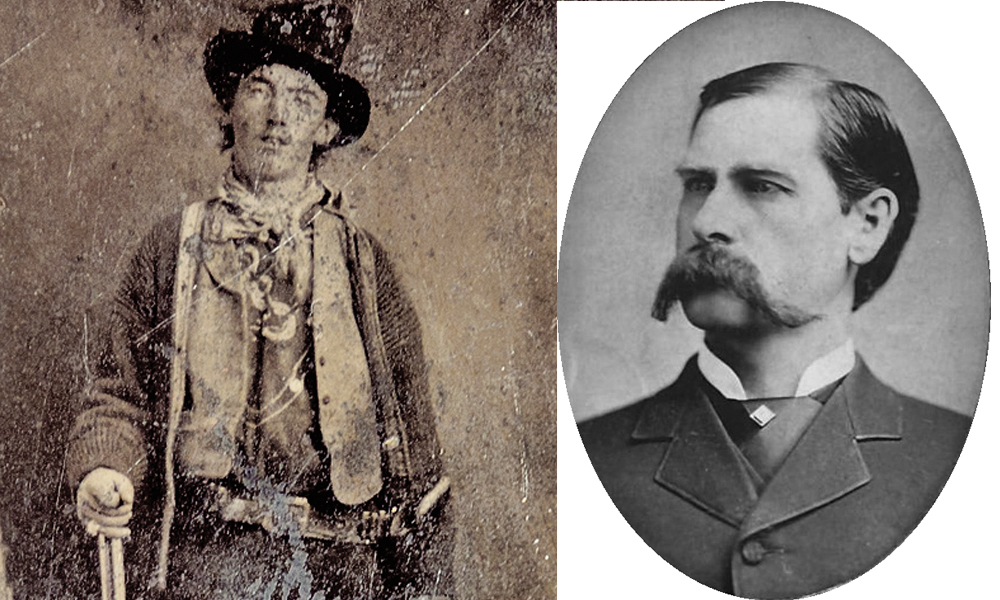

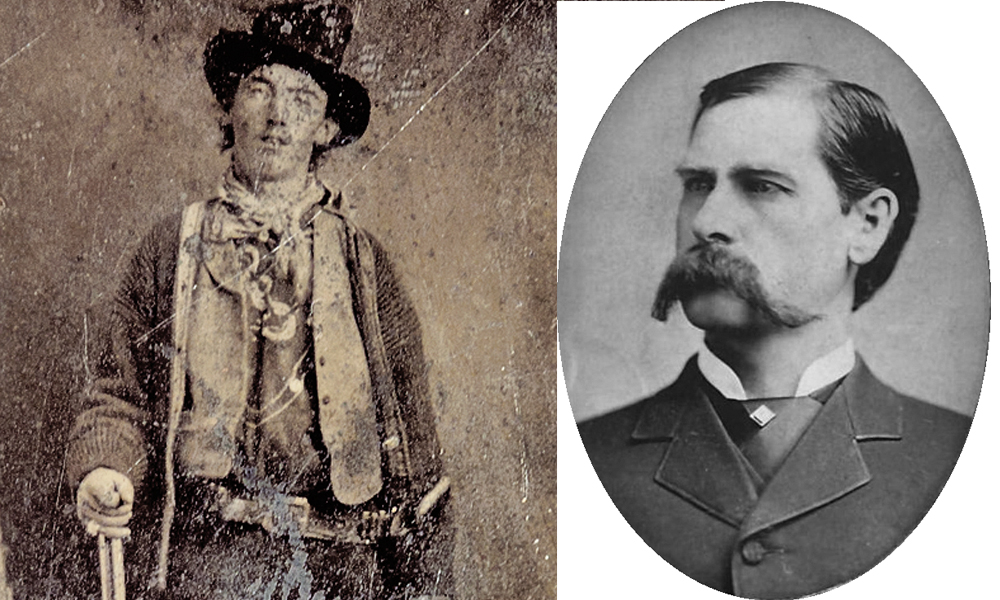

Here’s a historical question not often asked: Did Billy the Kid and Wyatt Earp almost shoot it out over drinks the night of November 27, 1879 in the Butter Bar in Jerome, Arizona Territory?

Here’s a historical question not often asked: Did Billy the Kid and Wyatt Earp almost shoot it out over drinks the night of November 27, 1879 in the Butter Bar in Jerome, Arizona Territory?

Writer William Wingfield says it’s true—wrote it all down in 1946 in a piece printed by Hartcort Press entitled Jerome–the Wickedest City.

Wingfield said he was there, in that very bar, run by Jerome Madam Nora “Butter” Brown, on that very night, and while he never heard any names exchanged, Nora herself later identified the drinkers. “I saw most of what transpired so I know that at least the bulk of it is true,” he reported, noting he got the whole story in 1903 when he and his secretary visited Nora at her home in San Diego and recorded her exact words. He illustrated his story with a revealing pic of an old west “soiled dove.” Whether that was Nora herself, it is not known.

But these are Nora’s words as she told the story:

“You remembers how we was drinkin that night. Well, come along some time after dark, the first of ’em walks in, and he’s got that long drover’s coat on, all dusty ‘n all from the road I found later, ‘n you know he just kinda joins in with us tippin’ the bottle. Being young as he was, he could sure hold his liquor. Seemed the drunker he got, the funnier he was. All the boys likened to him right away. Said his name was Henry. Said he had just delivered a passel of cattle from the New Mexico Territory to ole Boss Head down in the valley and had heard that there was a cat house going on up at the camp and just had to check it out for hisself. He wasn’t a big fella and actually he was kind of funny looking, but there was something about him. On one hand, like I said, he got along with the boys right away, laughing and joking and such, but on the other hand there was somethin’ there that made you not want to get on his bad side. He carried two Colt 41s on him with their holsters hung backward on the side of each hip. Hadn’t ever seen anyone carry his guns like that. And they was slung low and tied down to his thigh. You had the feeling that he could make those Colts jump into his hands like pet rattlesnakes. You know, that was before all this dime novel stuff, glamorizing it all and all that hootchie-coo about the handsome romantic outlaws ‘n such. Nonsense. Anyway, it was all new to me. What did I know, for Christ’s sake? I was just trying to make my way, you know. You know how it was.

“Well, as I was saying, we was all gettin’ along famously ‘n talkin’ big about how we was going to do all kinda grand things, when the second outsider came in. Now, he was a fella of a whole different stripe. Tall, thin, quiet. Came in wearin’ one of those flat brimmed hats that’s wide in the brim so’s to keep the rain offen you. Had these tall leather boots on that came up to his knees. Black they was. I remember being struck by the idea he was a city fella. Had on a striped vest with that gold watch chain stretched from pocket to pocket. You remember that part. And he was carryin’ a Colt strapped to side his like ole Henry. Except he only had one hung in a normal way, and he seemed like he was shy about it. He tended to keep it covered by his long broadcloth coat. So he comes in and sits at a table across the room from the bar, quiet like. Course, I goes right over and starts talking to him. Took a bottle of rye and a couple glasses with me. I thought maybe cause of the way he was dressed that he might have some money to spend on a lady. Seemed like it’d be a good way to christen my house, you know.”

The guy didn’t seem much interested in a romantic interlude, but Nora noted the younger fella looking over with “a curious look in his eyes.” Finally, the kid comes to the table “with a big ole charming smile on his face like he wants to sell us something.”

She continues the story:

“’This a private party or can a friendly stranger join in?’ he asks as easy as you please. I look over to the fella I been talking with o catch his reaction and watch him size up the younger dude. I can tell he’s measurin’ him—how it’d be, toe to toe. His gaze lingers on the other man’s Colts. Colder eyes I’d never seen. He smiled then just a little. ‘Have a seat cowboy. I’ll buy you a drink’, says my man. Well the young man pulls up a chair and helps himself to a drink right out of the bottle on the table. Smilin’ all the while he fills up old cold eyes’ glass. Then he starts in. You could tell he was on the prod.

‘You look like a man who’s taken a wrong turn somewhere Look like you maybe oughta be dealin’ faro in some fancy saloon in Dodge or Abilene or somewhere like that. Look a little high tone for this poor establishment.’

Well, my man looks at him a second and says, ‘Just passin’ through, son. On my way to Tombstone. Join my family’.

‘Ever been to Dodge?’ asks the kid

‘I’ve been there’, says the tall one.

‘You know, I was in Dodge once. I think maybe I saw you there.’ At this point he reaches his hand across the table offerin it for a shake. ‘My name’s Henry McCarty. My friends call me Billy’.

My man shakes his hand and says, ‘Wyatt. Watt Earp.’ Well, at this point the smile on the young fella’s face just gets bigger.

‘Tell you the truth, Mr. Earp, I knew that. Saw you draw down on four drunk drovers one night in Dodge. Never seen anyone draw and shot as fast as you. It was quite a site. It made me wonder’.

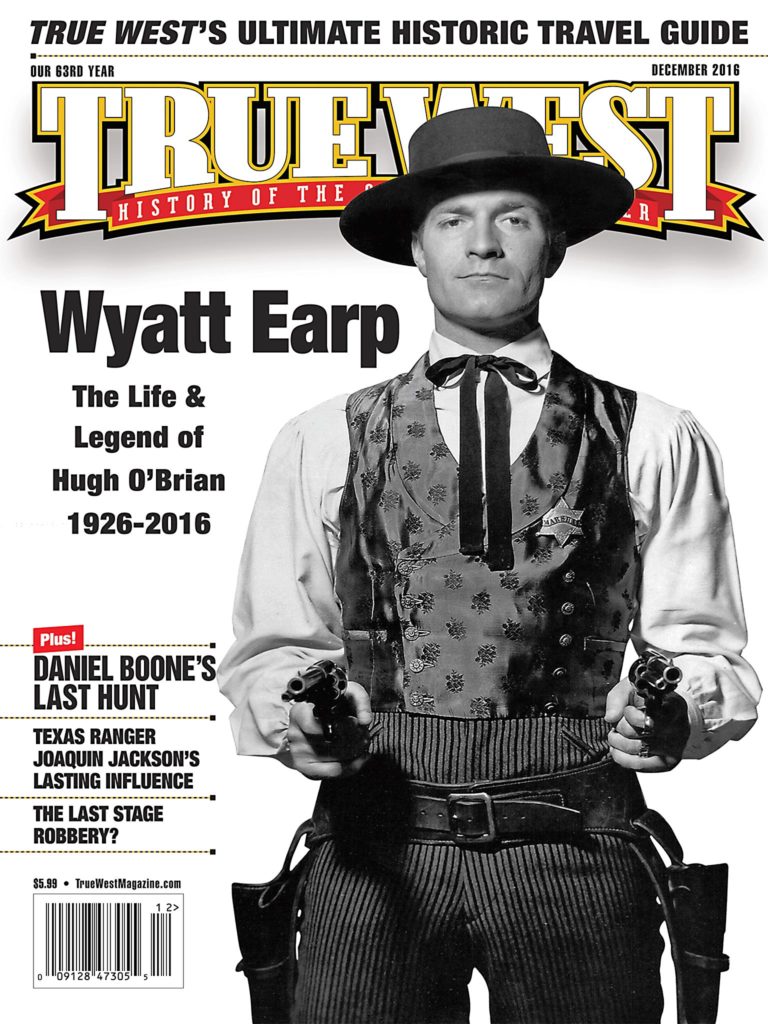

At this point, I began to get a little light headed. We had all heard of Wyatt Earp and the Dodge City Peace Commission with his friend Bat Masterson. He as a legend even then. As I was catchin my breath, I realized that neither man was speaking. They was just lookin at each other.

”What’s it make you wonder, Mr. McCarty?” I asked. Without taking his eyes offen Wyatt, he says, ‘It makes me wonder who’s faster with his gun. Me or Wyatt Earp’.

Wyatt’s all calm and slow. He takes a small drink of whiskey. ‘You don’t have to do this, son’, he says quiet like. I’ll tell you, both men seemed like they was spring loaded. All coiled up, ready to explode.

‘Oh, I don’t know, Mr. Earp. I think I just have have to,’ says Henry still smiling to beat hell.

Who knows what might have happened next if we hadn’t heard the gunfire and yellin.”

Nora recounts how at that very second, someone ran in yelling that Apaches were stealing all the horses, and folks went running out into the street. “But Wyatt, he’s as cool as a man on a Sunday promenade. His pistol comes out of nowhere, and he’s about to start laying in to the redskins when, suddenly, the kid puts a cocked Colt to Wyatt’s ear. ‘Just move real slow there, Mr. Earp. That’s it. Easy does it’. As he’s talkin’, he’s reachin’ for Wyatt’s gun. ‘I’ll be relieving you of that nice peacemaker you got there’. Then he sticks Wyatt’s pistol in the waistband of his breeches.”

Four or five Indians rode up, rifles ready, covering the crowd. Nora admits she was so scared she “actually wet myself,” and was astonished to discover Billy was in cahoots with them in stealing the horses. As he rode off with them, she heard him tell Wyatt, “Maybe some other day, Mr. Earp. Once I get paid for these horses, maybe I’ll look you up in Tombstone. How’d that be?” And she heard Wyatt respond, ‘Be my pleasure, Henry.” She noted Wyatt never showed“one wit of emotion.”

As he rode off, the kid, “still smilin’ like its all one big church social,” Henry yells back, “Billy, my friends call me Billy.”

Everyone was very relieved all the drama was over and went back inside to drink even more. And that’s when Nora’s favorite part of this story begins.

“Well, as fate would have it, I did finally get to christen my business that night, although I never did get paid. That whole horse thievin’ affair seemed to fire Wyatt up—got his blood boiling so to speak. It wasn’t too much later that we adjourned to my chambers upstairs. Now, don’t you go askin’ for no rude details. A lady does not speak of such things, but I will say that Wyatt stayed the whole night, and it was truly one of the most satisfying evenings of my life. It’s not often that a woman has the opportunity to bed a legend. The funny thing is that when I look back on it now, I realize that I probably owe it all to that rascal Billy. If it hadn’t of been for him I might never have had the chance to trade love’s sweet favors with the likes of Wyatt Earp.”

Author William Wingfield went on to become a successful rancher in the Verde Valley and lived to be ninety-two years old, dying in his sleep at home in 1951. As he penned this story, he stressed, “Butter said it was true, and I believed her.”