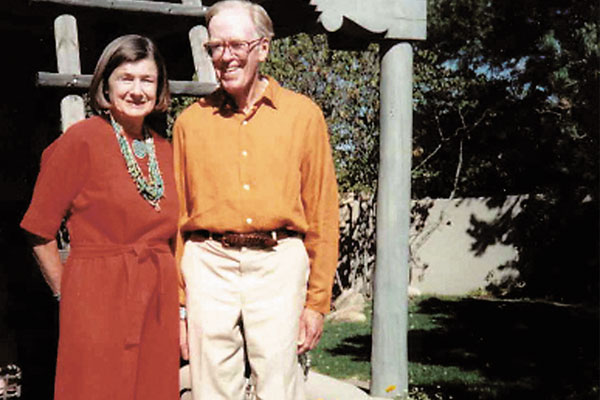

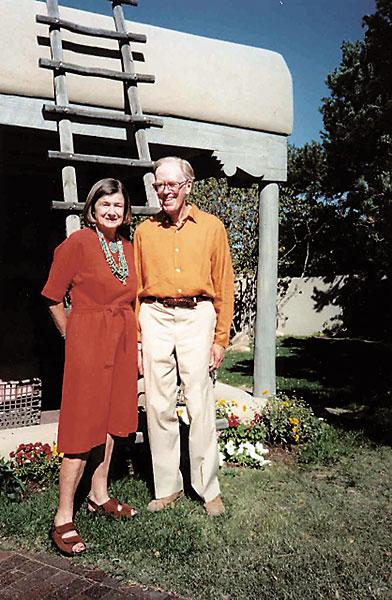

The Phillips family always loved their annual summer trip to Santa Fe from their California home in the 1950s and ’60s.

The Phillips family always loved their annual summer trip to Santa Fe from their California home in the 1950s and ’60s.

In the Hopi land of northern Arizona, Gifford and Joann Phillips would buy large katsinas from artists at roadside stands, while their daughter, Marjorie, would spend $5 on small katsinas.

By the time they got to northern New Mexico, they were among the Pueblo people. The parents struck up a friendship with their neighbor, Alfonso Ortiz, an Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo native and an anthropologist who taught at the University of New Mexico. This friendship laid the groundwork for one of the more unusual foundations in the country.

“We were interested in Pueblo culture—we loved the dances and collected a lot of artifacts: the baskets, old tapestries, the weavings, the blankets,” Gifford says. “I became interested in helping preserve the culture and feared with Santa Fe and Albuquerque growing, it would be wiped out.”

He chuckles, remembering the miscues he was ready to pursue until Dr. Ortiz set him straight. “I thought about offering a prize for the best essays, but he told me Indian culture is not competitive and that would never work,” Gifford says. “I suggested a lecture series about the importance of the culture, but he told me there weren’t many good lecturers on the subject, and the few there were, everyone had heard. So he helped me create the Chamiza Foundation.”

Named for the plant that grows throughout Pueblo land—ironically, Gifford is allergic to the plant—the foundation gives grants, primarily to Pueblo people, to sustain tribal life and traditions.

“For much of what we do, there’s nowhere else to turn,” says Marjorie Phillips Elliott, now chair of the Chamiza Board of Directors, which includes several Pueblo members. “We gave a grant to fix a pottery shed. This summer we’re paying stipends to elders to teach kids traditional farming. We do a lot of start-up funding.”

Since 1989, the Chamiza Foundation has issued nearly 350 grants—90 percent directly to Pueblo members—worth more than $2.3 million. The first grant was given to the Eight Northern Pueblo Indian Council for an awning for its annual art fair. Another early grant aided the development of a dictionary for the San Juan Pueblo tribe.

Marjorie was not surprised her parents would pledge their wealth to a foundation like this. “Our summer trips showed them there was so much we could learn from the Pueblo culture,” she says. “And their deep admiration of the art evolved into a deep admiration of the culture. They were looking for something specific—how can we give back after so much pleasure over the years of going to the dances and collecting

the artwork?”

Remember those katsinas Joann collected? She recently donated the dolls, which for years hung in her kitchen, to the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Arizona. “The kachina collection isn’t quite as good as Barry Goldwater’s, but it’s pretty good,” Gifford says. (Marjorie says her own collection of little katsinas hangs in her kitchen in Princeton, New Jersey.)

The cornerstone of the foundation’s success is its partnership with the Pueblo people. “They know what they need, we don’t—we’re outsiders,” Executive Director Donna Vogel says. “That the foundation is 20 years old is a testament to the way it works with respect and partnership. It’s the only foundation that works in this way.”

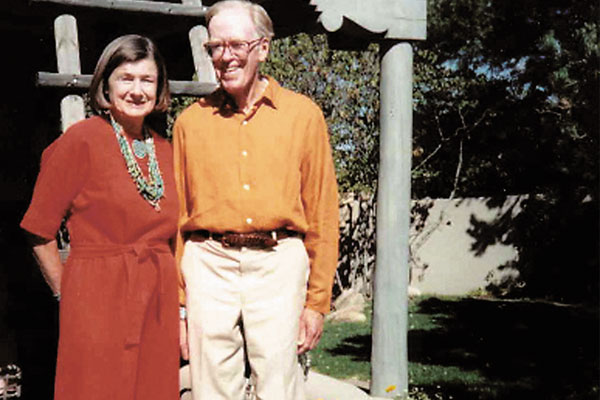

For this unusual foundation, Gifford and Joann Phillips were honored with a Lifetime Achievement Award from New Mexico’s Department of Cultural Affairs. “It’s been a great experience,” Gifford says, “but I couldn’t have done it without my very good friend, Alfonso Ortiz.”

Jana Bommersbach has been Arizona’s Journalist of the Year and has won an Emmy and two Lifetime Achievement Awards. She is the author of two nationally-acclaimed true crime books and a member of Women Writing the West.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy New Mexico Historic Preservation Division –

Polka dots and extravagant ears are characteristics of Wilson Tawaquaptewa’s figures. Joann Phillips donated this katsina to the Heard Museum. These dolls are also known as kachinas, an Anglicized term of katsina (the Hopi language does not have the “ch” sound).

– Courtesy Heard Museum –