Just how or why John Wayne first came upon the idea of making a movie about the Alamo is possibly the only mystery remaining in a movie that has been examined and covered from every imaginable angle during the past 50 years since its premiere.

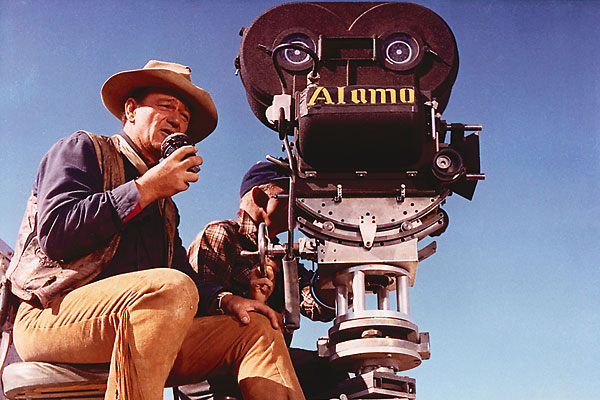

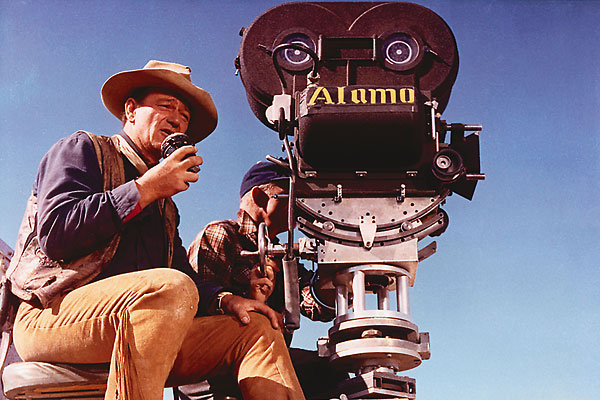

Long before a single camera was cranked or an extra dressed up in a period costume, photographers, camera crews, journalists and press reps wandered around the set; The Alamo was one of the press-friendliest movies in history. Wayne was making sure that the world was watching; it was his baby, his first attempt to direct a film and the story he’d wanted to make for years.

The fact that Wayne was a publicity hound is actually a good thing for Alamo buffs and fans of Westerns and Wayne, because it means books have taken advantage of all that material, books such as John Wayne’s The Alamo: The Making of the Epic Film by Donald Clark and Christopher P. Andersen (if you can find it) and the lavishly illustrated, rather pricey (but worth it) The Alamo: A Visual Celebration of John Wayne’s Epic Movie by Lee Pfeiffer and David Worrell.

Inspiration Junction

Around 1945, Wayne decided he would turn the Alamo battle into movie-making history. Yet what turned the actor onto this 1836 battle that buoyed Texians for revenge and ultimately put an end to the Texas Revolution?

Historian and journalist Garry Wills, who wrote 1997’s John Wayne’s America, may have nailed the source. He recalls that the father of one of Wayne’s closest friends from his early Hollywood days, Robert Bradbury, directed a 1926 silent film called Davy Crockett at the Fall of the Alamo (the first Crockett film was made in 1909). The teenaged Wayne may have even been on set while the movie was being filmed.

Actor as Director

These days an action star like Mel Gibson can make a movie as strong as 1995’s Braveheart and Kevin Costner can direct and star in 1990’s Dances With Wolves, whereas in 1960, stars like Wayne did not often put themselves in the driver’s seat.

Yet Wayne’s acting contract with Republic Pictures offered him the chance to launch his own pictures under the Republic umbrella. In 1947 Wayne produced and starred in Angel and the Badman, which was written and directed by his friend and former Chicago journalist James Edward Grant. Grant went on to write many of Wayne’s more iconic films, such as 1953’s Hondo and 1963’s McClintock. Wayne spent nearly 15 years working with Grant on his script for The Alamo.

Wayne first approached Republic president Herbert J. Yates in the late 1940s with the idea of making an Alamo film. Yates, by all accounts, kept Wayne believing the film might happen. But as time rolled on and Wayne was hitting a series of career highs, the actor grew frustrated, grabbed his shingle and left Republic.

A couple of years later Republic did make an Alamo movie, 1955’s The Last Command, starring Sterling Hayden as Jim Bowie and the wonderful Arthur Hunnicutt as Davy Crockett. The flick may have pinched some ideas from the movie Wayne pitched Yates, because certain fictions are the same in both pictures (such as having Crockett, seconds away from being skewered by Santa Anna’s soldiers, tossing a torch into a roomful of gunpowder and going out in an explosion of glory). Yet given that screenwriter Warren Duff was a veteran of a good many first-rate Warner Brothers pictures and the producer of 1947’s Out of the Past, I find it difficult to imagine Duff would deliberately lift anything from Wayne’s project.

In any case, The Last Command is much less of a spectacle than The Alamo, but in some ways it’s as good or better, especially where the writing is concerned. Interestingly, both films were shot in Brackettville, Texas, where you can still see the Alamo replica Wayne commissioned to be built for the movie (unfortunately Alamo Village is no longer open for tours).

By 1959 Wayne had everything in place to make his Alamo movie. He had the financing, the studio and the locations. He had the set designer, his cast (loaded with character actors from dozens of Wayne’s other films) and his cinematographer. He also had the score composed by Dimitri Tiomkin, the same man who had written the music for 1948’s Red River, 1954’s The High and the Mighty and 1959’s Rio Bravo.

In making the film, Wayne did make at least one compromise. He had no desire to play Crockett, either because he needed more time to direct and less to act, or perhaps because he didn’t want to tackle a part that Fess Parker owned. Wayne was more interested in playing Gen. Sam Houston, a much smaller part in the film. Yet the investors were determined; Wayne as Crockett was a deal maker, so he forged on to play the frontiersman in his last days of life.

A S.A.G.’s Critique

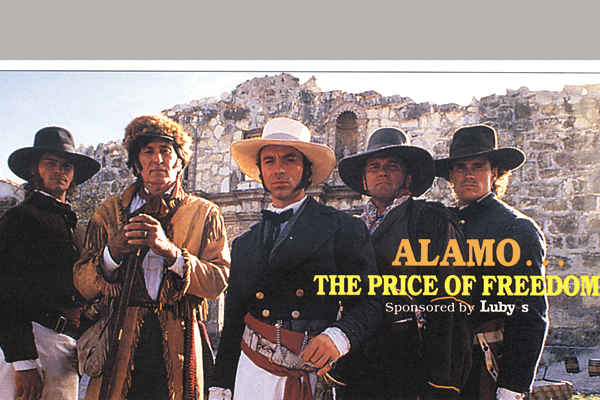

Today legions of fans remain devoted to the movie, and to the historical event that should have informed it (the classic is not nearly as accurate as director John Lee Hancock tried to be in 2004’s The Alamo). Yet even diehard fans admit Wayne’s Alamo features flat and sometimes overwrought writing.

Rick Hassler, a journalist based in El Paso, Texas, belongs to an elite group of friends who discuss the movie and the battle in details:

“I’ll tell you … John Lee Hancock calls us Alamo nuts, Alamo heads and Serious Alamo Guys—‘S.A.G.’ It might not be known to anybody outside, but if you call somebody a SAG, you know it’s a fellow Alamo guy.”

Hassler was first exposed to the movie at the age of seven. “People were getting blown up on the big screen, run through with bayonets and swords and stuff. I just enjoyed the spectacle,” he admits. “John Wayne playing Davy Crockett—how much better can it get? Even though when he spouts some of those homespun lines—such as, “You can’t get lard lessen you boil the hog”—well, there are things that he doesn’t quite get right.”

Yet in spite of Wayne’s experiences in front of the camera, he was not a natural director. He lacked the instincts of the greats who had directed him, such as John Ford, Howard Hawks, Henry Hathaway and William Wellman.

For instance, Richard Widmark as Bowie comes across as flat and disinterested. The stories that came from the production suggest that Wayne and Widmark were at odds politically, but I’d wager that the problem was a matter of chemistry, and in Widmark possibly lacking confidence in Wayne as a director.

On the other hand, Chill Wills chews more scenery than Santa Anna’s cannons in his role as Crockett’s companion Beekeeper. Somebody should have slipped him a mickey. When the picture finished, Wills launched an aggressive campaign to get a supporting actor Academy Awards nomination, which actually had the opposite effect—it nearly killed any chance the picture had of being recognized by the Academy, and Wayne had to publicly distance himself from Wills’s efforts. But when the time came, The Alamo brought in six nominations and one win, a tech award, for sound.

All in all, Wayne did a darn good job for a first-time director. The scene that comes the night before the final battle is especially fine.

“The best line in that movie,” Hassler says, “is when he and Thimblerig [Denver Pyle] are sitting over there on the wall and Thimblerig says to him, ‘What are you thinking, Davy?’ Wayne replies, ‘Not thinkin’, just rememberin’.’ That line sent chills up and down my spine.”

Wayne’s Patriotic Fervor

In 1960, the drive-ins and indoor theaters were loaded with couples and friends and families who knew what going to a John Wayne movie meant. The Alamo was Wayne in spades. It was big and loud and proud; it was Wayne, or rather the screen character Wayne played, personified.

Yet why did the famous actor want to work on The Alamo project in the first place? His wife suggested he wanted to make the movie due to his unease at not having served in WWII. Wayne may have felt that his patriotism and ideals needed expressing in the profoundest and grandest possible way.

In A Line in the Sand: The Alamo in Blood and Memory, by Randy Roberts and James S. Olson, Wayne’s daughter Aissa says, “I think making The Alamo became my father’s own form of combat. More than an obsession, it was the most intensely personal project in his career.”

Wayne was also convinced that The Alamo was a commercial project. Wayne would never have thought to make a movie that he didn’t think his fans would want to see. Wayne was many things, but no one ever accused him of having artistic pretensions. And The Alamo did in fact make money. Wayne had to sell his interest in the picture to United Artists to make back his investment, but he said several times that everybody made money on the movie but him.

Have You Seen the Original Alamo?

After the initial road show engagement, The Alamo, which ran 192 minutes, was cut by Wayne, who removed 30 minutes of footage. The cut included a lengthy birthday party sequence featuring Wayne’s own daughter Aissa, who was barely a toddler at the time, as the birthday girl. For years no one could find the missing footage on an intact print, until one turned up in Toronto. That print was used to created a laserdisc edition of the film and a VHS release. Unfortunately, fans who are desperate to get a look at the full version will have to snag a cassette or a laserdisc version on e-Bay, because the 70mm print that provided the longer cut was damaged by MGM. At this point only a master restorer with a substantial capital investment would, possibly, be able to restore the film.

“Robert Harris is trying to find funds to restore the movie right now,” says Lee Pfeiffer, co-author of The Alamo: A Visual Celebration of John Wayne’s Epic Movie. “He restored many Hollywood film classics, including Lawrence of Arabia and Vertigo. That said, the long version is not better than the shorter version, but it is interesting to see what was cut: primarily a birthday party, the death of the villain Emil Sande and Crockett speaking over the dead parson during the battle. None of these scenes significantly impact the story.”

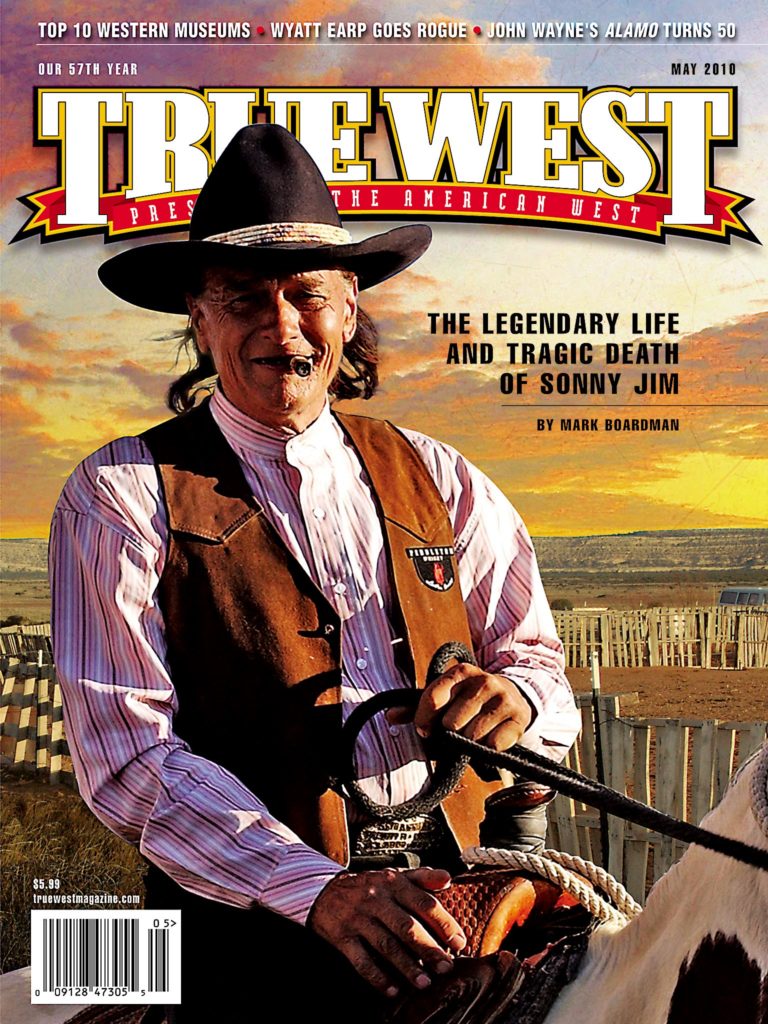

Even though MGM doesn’t apparently have any desire to make a special anniversary edition DVD available, or even a blu-ray edition of the current DVD, a 50th anniversary screening of The Alamo will take place at John Wayne’s Birthday celebration in Winterset, Iowa, on May 28-29. The folks there really load up these annual celebrations, and this year the guest of honor will be Aissa Wayne, the star of the birthday party scene that later got cut from the movie. The John Wayne Birthplace Museum will also be hosting a fundraiser for the new learning center it hopes to build to make it the only museum dedicated to the world-renowned actor.

Fifty Years Later

Fifty years after The Alamo premiered, the political hot button issues of John Wayne’s day are present once again in ours, with right versus left and blind catchphrases like “socialism” being tossed about in exactly the same way they were in the 1960s, when the Civil Rights movement, missiles in Cuba and the Cold War got white hot.

For Wayne, it was a tough time politically. The Eisenhower era was at an end and two weeks after Wayne’s movie premiered, John F. Kennedy, who Wayne strongly opposed, was elected President. The times were definitely a-changin’. Were Duke Wayne around today, he’d probably feel about Obama the way he felt about Kennedy.

The Alamo may have also had some allegorical import for Wayne. Wayne saw Gen. Santa Anna and his Mexican warriors as mirroring the Soviets in some fashion. Yet, overall, Wayne’s Alamo is a simple story of brave men who made a choice, knowing they would die—everything else is background. Similar events can be found in history, such as the battle at Thermopylae, where the Spartans stood their ground against the Persian horde.

Allegory or simple heroics, Wayne’s version of the battle of the Alamo is as moving as any version that came before or since. Wayne managed to see a dream he carried made real, and 50 years later, that dream lives on, as does the Duke.