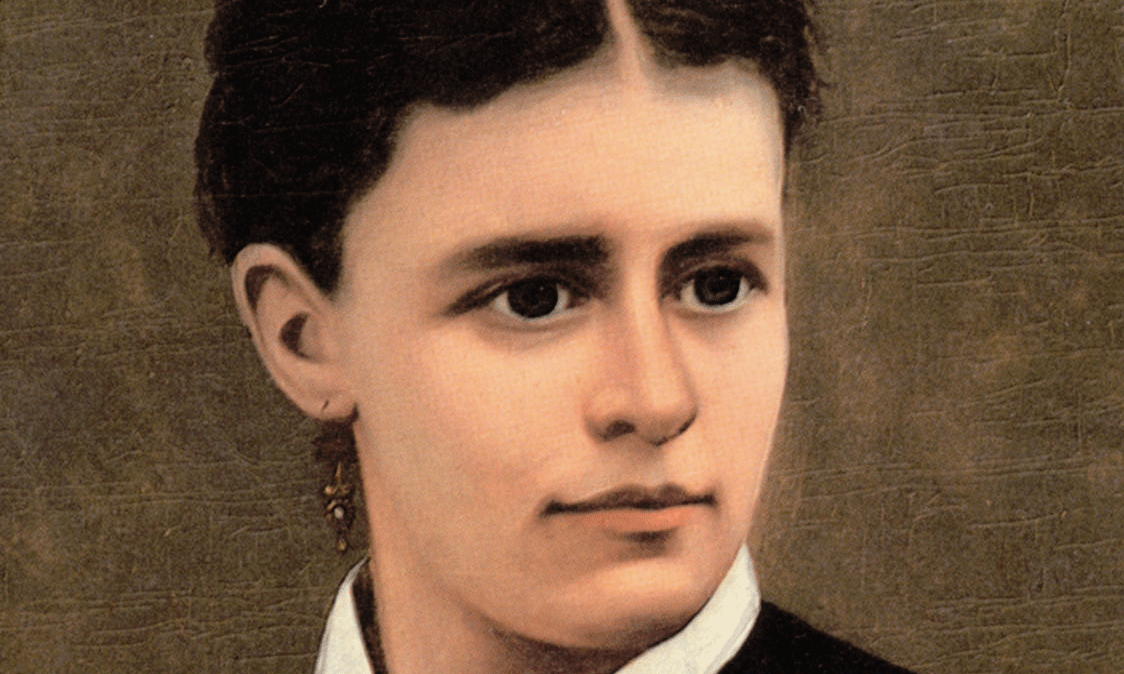

America’s first female explorer was a teenager and new mother who carried her infant on her back as she walked across half the country.

America’s first female explorer was a teenager and new mother who carried her infant on her back as she walked across half the country.

She was a guide who wasn’t paid a cent, and Lewis and Clark wouldn’t use her real name on a single landmark. But Sacagawea would end up just as famous as the men who claimed the West for the United States and would become the most celebrated American woman of any color.

We met her first in a cryptic note written with peculiar spelling by William Clark on November 11, 1804, from the newly-built Fort Mandan in Dakota Territory: “Two Squars of the Rock mountains, purchased from the Indians by a frenchman came down.”

One of those two women was 16-year-old Sacagawea, the other was her friend, Otter Woman. Both had been captured about five years earlier by Hidatsa Indians and brought from their original home in the Rockies with the Shoshoni tribe, or “Snakes,” as they were sometimes called. Both ended up as wives of a French-Canadian named Toussaint Charbonneau.

He passed himself off as an interpreter and was hired on with the Corps of Discovery expedition financed by President Thomas Jefferson. In truth, Charbonneau wasn’t much of a linguist and, at one point, so ticked off Lewis and Clark that he was fired. He was only rehired after they discovered his teenaged wife was a Shoshoni. That was important for two reasons: she knew her native language, and the Shoshonis had horses. The explorers thought they might need horses for a short overland trip between the Missouri River on which they were traveling and the river they believed would take them all the way to the Pacific. (That this mythical river didn’t exist would be one of the great disappointments of this trip.)

While they would eventually pay Charbonneau $500.33 for his efforts, they got Sacagawea for free—it would be the best deal they ever made, for at least twice she saved the expedition.

The Rattle of a Snake Helped

On February 11, 1805, on the floor of a tiny cabin inside Fort Mandan, Sacagawea gave birth to her son. As Meriwether Lewis described it, “Her labour was tedious and the pain violent.” One of the crew said the rattle of a snake would hasten the birth and in desperation, Lewis agreed. She ate two rings of the rattle and about 10 minutes later, gave birth. Lewis was so awed by all this, he recorded the whole story in his journal. Although the baby’s official name was Jean Baptiste, Sacagawea called him Pomp, which in Shoshoni means “firstborn.” William Clark would come to love the boy and call him “my Pomp.”

The expedition left Fort Mandan on April 7, and in his journal that day, Clark listed all the members of the party, including “Carbonneau and his Indian Squar to act as an Interpreter and Interpretess for the snake Indians.”

She quickly proved herself calm in disaster and literally saved the trip from ruin. On May 14, with both leaders walking on the bank, the boat containing all their instruments, books, medicines and “almost every article indispensably necessary” almost capsized. It was Sacagawea who calmly grabbed the items being washed overboard. Lewis praised her in his next journal entry for “her equal fortitude and resolution.”

Within a week, they named the Bird Woman River after her, apparently believing the white translation of her name was more memorable than her difficult Indian name. (And to this day, the spelling of her name

is debated: Sacajawea, Sakakawea or Sacagawea.)

She would again save the expedition in August, when she was miraculously reunited with her brother, the chief of the Shoshonis. They met at a very tense moment. Meriwether Lewis had led the advance party to find the Indians and negotiate for their horses. But the Indians viewed these white men suspiciously, and it was becoming increasingly apparent that without their horses, the expedition would have to turn around and go home. All that changed when Sacagawea showed up with Clark’s band and showed “extravagant joy” in discovering her brother Cameahwait. He and an orphaned nephew were among the few remaining members of her family, and she “immediately adopted” her nephew.

As she vouchsafed for the expedition and secured promises for the essential horses, she obviously had to face her own personal crossroads. “After years of separation from her family, her culture and her homeland, she had now returned after a long and arduous journey,” reports historian Dorothy Gray in Women of the West. “The most natural thing in the world would have been for her to have chosen to stay” with her people.

But she learned her brother intended to renege on his promise of horses and guides—taking his people instead on a hunting trip to replenish the tribe’s food supply. Sacagawea “elected to tell Lewis and Clark that Cameahwait was backing down on his commitment,” Gray notes. “In betraying what must have been her brother’s confidence she severed the tie with her own people completely and threw in her lot with the white men.” Gray surmises this was because Sacagawea understood the importance of the journey and wanted to help it succeed.

Her actions helped make that happen—Clark was able to convince the chief to postpone the hunt. Cameahwait provided horses and guides that got the Corps of Discovery through the Rockies.

America’s First Female Voter

As the expedition reached its goal—the Pacific Coast in Oregon—Sacagawea made American history by being the first woman ever allowed to vote. Her voice was added to all the others in voting where to locate their winter fort, and while it may not have been the most significant vote in history, it is historic because it would take the nation more than a century to amend its constitution to grant women suffrage.

The expedition returned to Dakota Territory in August 1806, and she and her husband remained in Mandan as the rest of the explorers went on to their homes in the East. Clark, who was particularly fond of her and her child (he called her “Janey”), offered to educate Pomp. When the boy was old enough, he went to St. Louis under Clark’s guidance. He studied there and in Europe before returning to the West.

Some historians are still debating Sacagawea’s death—and several tribes, all of them claiming her for their own, maintain she lived to old age in the 1880s. But two pieces of evidence place her death much earlier. On December 20, 1812, at Fort Manuel on the present-day border between North and South Dakota, the clerk noted the death of “the wife of Charbonneau, a Snake squaw…. She was the best woman of the fort, aged about 25 years.” In 1828, Clark wrote out a list of the exploration members and noted, “Se car ja we au Dead.”

Her fame started to grow as the 19th century came to a close and continues to this day. In 2000, Congress gave her the rank of sergeant in the U.S. Army.

Eventually, an avalanche of books would be written about her, while monuments and places were named in her honor. One of the most important was a statue in Portland, Oregon, which was unveiled during the 1905 Lewis and Clark Exposition.

The statue was dedicated by two leading voices for women’s rights: Susan B. Anthony and Abigail Scott Duniway. It shows Sacagawea with her arm outstretched to point the way, wearing fringed buckskins with her baby on her back.

Duniway’s words that day were power-ful, notes Judy Alter in her Extraordinary Women of the American West. “This woman was an Indian, a mother, and a slave…. Little did she know that she was helping to upbuild a Pacific empire…. In honoring her, we pay homage to thousands of uncrowned heroines whose quiet endurance and patient efforts have made possible the achievements of the world’s great men.”