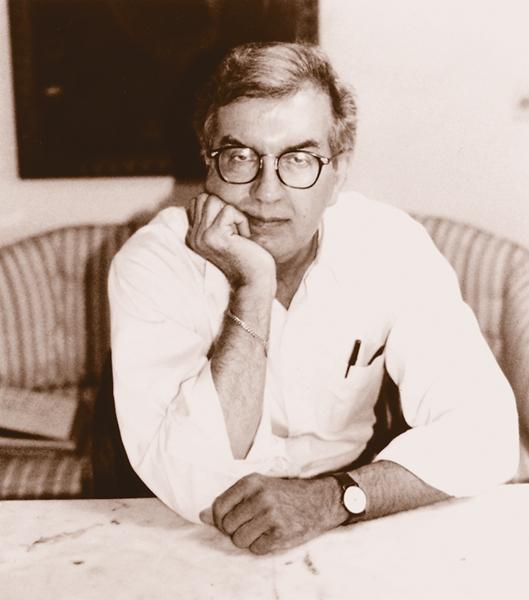

“The West,” Larry McMurtry wrote in his 1968 essay “Southwestern Literature,” “has produced many good books but perhaps, as yet, no great books.”

“The West,” Larry McMurtry wrote in his 1968 essay “Southwestern Literature,” “has produced many good books but perhaps, as yet, no great books.”

That was 17 years before the publication of Lonesome Dove, which was to win the Pulitzer Prize and, in the minds of many, earn the unofficial title, “The Greatest Western Novel Ever Written.”

If Lonesome Dove is the greatest Western ever written, then, together with its precursor, Comanche Moon (currently being made into a miniseries due out in 2007), and successor, Streets of Laredo, the three must count as the greatest of all Western trilogies. Whether or not McMurtry’s novels are very good or great is a question that the literary establishment, most of which is centered in the Northeast, has yet to come to terms.

For his own part, McMurtry makes no grandiose claims about his own place in American letters. Whenever he writes about his own work, it’s usually in terms of specifics. For instance, in his 1999 nonfiction work about growing up in Texas, Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen, he explained that one of the things he’d been trying to do in his novels is fill in the emptiness of the West his ancestors knew, “peopling it, trying to imagine what the word ‘frontier’ meant to my grandparents (as opposed, say, to what it meant to Frederick Jackson Turner, already a coat-and-tie professor at the University of Wisconsin while my grandparents were building their first cabin and begetting yet more McMurtry quail on that hill in Archer County).”

For McMurtry, reimagining the West of his ancestors meant undercutting the romantic clichés of the best-known Western writers: “My experience with Lonesome Dove and its various sequels and prequels convinced me that the core of the Western myth—that cowboys are brave and cowboys are free—is essentially unassailable. I thought of Lonesome Dove as demythicizing, but instead it became a kind of American Arthuriad, overflowing the bounds of genre in many curious ways. And in two lesser novels, Anything for Billy and Buffalo Girls, about Billy the Kid and Calamity Jane, respectively, I tried to subvert the Western myth with irony and parody, with no better results. Readers don’t want to know and can’t be made to see how difficult and destructive life in the Old West really was. Lies about the West are more important to them than truths, which is why the popularity of the pulpers, Louis L’Amour particularly, has never dimmed.”

If that’s true, it is also true that the enormous popularity of McMurtry’s novels stand as a counter to the myths of L’Amour, Max Brand and Zane Grey. In fact, in many ways, the influence of McMurtry has been stronger than that of all the most popular pulp Western writers if only because his readership extends far outside the boundaries of what he calls “the pulpers.” One can make a convincing case that McMurtry’s vision of the American West, expressed through his novels, screenplays and essays, is probably more pervasive than that of anyone except John Ford. McMurtry’s vision is deeper, darker and more inclusive than Ford’s was. McMurtry country extends from the mythic era of the Texas cattle drives in Lonesome Dove to the suburbs of modern Houston in Terms of Endearment. Peter Bogdanovich’s film version of McMurtry’s novel, The Last Picture Show, was justly praised for its Ford-like qualities, but in truth, the clarity and toughness of McMurtry’s script dispelled the romantic mist of Ford’s West. One can only imagine what Ford might have thought of McMurtry and Diana Ossana’s script for Brokeback Mountain, which won the Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay this year and reveals a West John Wayne wouldn’t have dared admit existed. (One also wonders what Ford might have thought of McMurtry wearing a tuxedo jacket and blue jeans when he accepted the Oscar; see p. 27.)

It’s ironic, perhaps, that McMurtry would have played an important part in the most controversial screen Western in history, the first film about openly gay cowboys. (Though Ossana, who was also McMurtry’s writing partner on two novels, Pretty Boy Floyd and Ned and Zeke, pointed out in a radio interview, “Ennis Del Mar and Jack Twist really aren’t cowboys, they’re failed cowboys. They’re sheepherders.”) It was McMurtry, after all, who once wrote in a famous autobiographical essay, “Eros in Archer Country,” “I think it would be facile to assume … that most cowboys are repressed homosexuals. Most cowboys are repressed heterosexuals.” Still, in Brokeback Mountain, Ennis and Jack are products of the West that Woodrow Call and Augustus McCrae of Lonesome Dove helped create, or rather, they are all products of a West which Larry McMurtry helped create.

The real American West is enormous, but it has limits. Yet there are no limits to the boundaries of the fictional West. Nearly 40 years ago, McMurtry thought, “The appeal [of the cowboy] can’t last forever. The West definitely has been won, and the cowboy must someday fade.” The Westerner, he felt, “is gradually being challenged by more modern figures,” such as James Bond. Now, it is James Bond who seems dated while the cowboy—whether represented in the traditional mode by Kevin Costner and Robert Duvall in Open Range, or as a comic parody by Jackie Chan and Owen Wilson in the Shanghai movies, or by Tommy Lee Jones, Sam Shepard, Edward Norton or Heath Ledger and Jake Gyllenhaal in any of several new adult contemporary Westerns—seems more relevant than ever. The man most responsible for keeping the West alive in our imaginations and making the Western evolve is Larry McMurtry.

The West is indeed big country, and so far, although some would push Larry McMurtry into the “Westerns” corral of the local bookstore, no one has succeeded in fencing him in.

Acting Out McMurtry’s Novels

Not counting Comanche Moon, which is currently in production, 10 of McMurtry’s novels have been made into feature films, TV movies or series. Here are the five best (his other five are: Lovin’ Molly, 1974; Texasville, 1990; Streets of Laredo, 1995; The Evening Star, 1996; and Dead Man’s Walk, 1996).

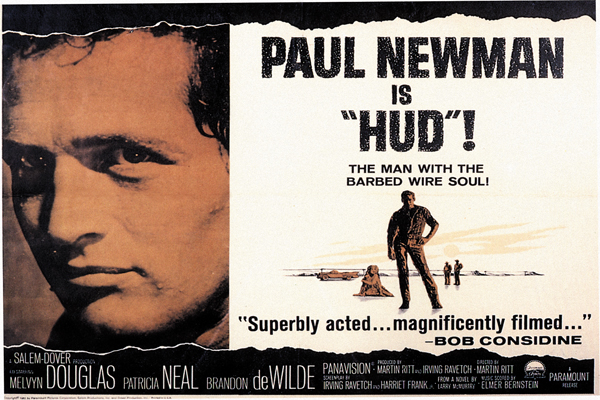

Hud (1963): Paul Newman is the contemporary cowboy in this enormously successful adaptation of McMurtry’s first novel, Horseman, Pass By, set, in the words of Pauline Kael, “in the Texas of Cadillacs and cattle, crickets and transistor radios.” Martin Ritt directed, and the starkly handsome black-and-white photography is by James Wong Howe. Patricia Neal, saying her lines in a sexy Texas drawl, plays the housekeeper of the Bannon ranch, and the knowing looks and sharp exchanges of dialogue between her Alma and Newman’s Hud give the film a constant tension and tingle. (Neal won an Oscar for best actress.)

Newman’s Hud is cold-blooded and unprincipled, representing the new predatory spirit of the West that is meant to contrast vividly with the earthy, 19th-century values embodied by his father Homer, played by Melvin Douglas. (If the film has a fault, it’s that the contrast between cattleman father and son, who wants to turn the land over to oil wildcatters, is constantly pushed in front of us.) Brandon DeWilde, who called to Alan Ladd to come back at the end of Shane, plays Hud’s teenage nephew, Lon. He does not call to Newman to come back at the end of this film.

Writing about Hud in his book, In A Narrow Grave: Essays on Texas, McMurtry wrote, “The screenwriters erred badly in following my novel too closely.” He is surely the first and perhaps the only novelist in history to make that complaint.

The Last Picture Show (1971): A landmark in American movies, The Last Picture Show is the first great success for Peter Bogdanovich and perhaps the harshest and greatest American film ever about the heartbreak and desolation of small town Western life, in this case, modeled after McMurtry’s hometown, Archer City, Texas, in the early 1950s. As with Hud, McMurtry judged the film version of his second novel to be better than the book. He may be right, but one of the reasons for the film’s greatness is the brilliance of McMurtry’s screenplay, which extracts and highlights the novel’s best features.

The superb cast includes Jeff Bridges, Timothy Bottoms, Ellen Burstyn, Cybill Shepherd, Eileen Brennan and two Oscar winners for supporting actor: Cloris Leachman and Ben Johnson. The latter plays “Sam the Lion,” proprietor of a pool hall as well as the town’s only movie theater. Sam rated one of McMurtry’s finest epitaphs: “He was a hell of a man,” says one character after Sam’s passing. “He had his own way of doin’ things.”

Terms of Endearment (1983): With the exception of Jack Nicholson’s raucous performance as a former astronaut, the best things about this blockbuster hit are from McMurty’s novel about a 30-year relationship between a mother and a daughter (exquisitely played in the film by Shirley MacLaine and Debra Winger). Directed by James L. Brooks from his own screenplay, the film is soft in precisely those places where McMurtry’s writing is sharp—it never quite gets around to, as the novel does, defining exactly what the terms of endearment are. But the production is redeemed by the showcase it provides for great actresses to strut their stuff. The film won five Academy Awards: Best Picture, Brooks for Best Director and Best Adapted Screenplay, Nicholson for Best Supporting Actor and MacLaine for Best Actress, making her the fourth actor to win an Oscar playing a McMurtry character.

Lonesome Dove (1989): Lonesome Dove is the Red River—no, let’s not understate it—the Citizen Kane of TV Western miniseries. William D. Wittliff wrote the screenplay, wisely sticking to McMurty’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel at nearly every turn. If Lonesome Dove in its 384-minute original length had been released intact as a feature film, it would be widely acknowledged as perhaps the best Western ever made. But then, it never would have been made at that length as a motion picture. Directed by Simon Wincer, the miniseries format allows the viewer to live in the world of Tommy Lee Jones’ Woodrow Call and Robert Duvall’s Gus McCrae in a way that even an epic theatrical Western would not have allowed. Once again, the cast for a film based on a McMurtry novel is impeccable, including Diane Lane, Anjelica Huston and Glenne Headley—playing three more great female characters by McMurtry—Danny Glover, Robert Urich, Chris Cooper, D.B. Sweeney and Frederic Forrest as the renegade half-breed Blue Duck, perhaps the most blood-chilling villain in the history of Westerns.

Buffalo Girls (1995): Clocking in at 180 minutes, this is probably the second best TV Western ever made after Lonesome Dove. If it has a major flaw, it’s that, like its predecessor, it would have been better at twice the length. Adapted by Cynthia Whitcomb from the most historical-based McMurty Old West Westerns, the film, directed by Rob Hardy, features perhaps the most accurate and vivid film characterizations of Calamity Jane (Anjelica Huston), Buffalo Bill (Peter Coyote) and Wild Bill Hickok (Sam Elliot). That they all seem comically aware of their future places in American folklore makes them even more interesting—after all, the real-life characters were certainly aware of theirs. Melanie Griffith is heartbreakingly lovely and appealing as the real-life brothel madam and author Dora DuFran, possibly the best role of Griffith’s career. Gabriel Byrne, Jack Palance, Floyd “Red Crow” Westerman, Tracey Walter, Russell Means, Liev Schreiber and Reba McEntire (as Annie Oakley) are all in the cast, and you wish you saw more of all of them.

Photo Gallery

– By Diana Ossana –

– True West Archives –

– Courtesy AP Photo / Kevork Djansezian –