You probably remember the story of Lt. John Dunbar.

You probably remember the story of Lt. John Dunbar.

During the Civil War, he goes crazy—and somehow rallies Union troops to a victory. Army commanders reward him by sending him to the post of his choice—one on the Western frontier that turns out to be abandoned. He stays, however, be-friending wolves and a local group of Sioux. And gradually, he throws away the trappings of white society and goes native.

That’s the Cliffs Notes version of Dances With Wolves, the three-hour long movie starring Kevin Costner that won a slew of 1991 Academy Awards. One of them went to the man who came up with the story and the script—Michael Blake.

He first became interested in Indians after reading Dee Brown’s 1970 classic Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. And since Dances With Wolves, Blake has written a couple of other novels about the conflicts between the Indian and white cultures in the 19th century.

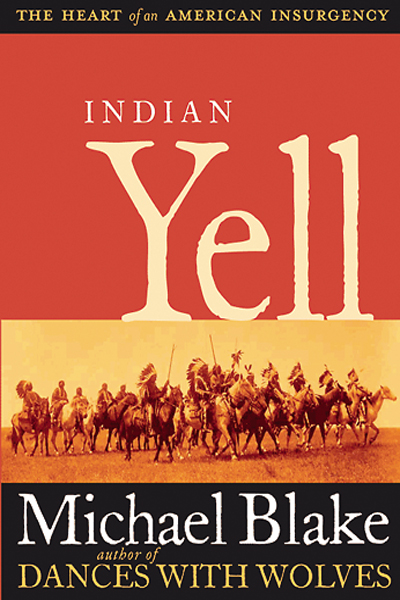

But it’s only now that Blake has turned his pen to nonfiction—and again, the Indian Wars are the subject of Indian Yell (Northland Publishing, 2006). It won’t surprise anyone who has seen Dances that Blake’s sympathies lie with the Indians—or that he views most government officials, military leaders and numerous other whites as treacherous, racist, greedy and downright ugly Americans.

In Chapter Five, “Island of Rotting Horses, 1868,” Blake details what he considers to be the stupidity of one army officer and how that led to the famed Battle of Beecher Island in Colorado. As this excerpt shows, it isn’t a pretty picture.

—The Editors

The border between Colorado and Kansas runs for three hundred miles, cutting through the absolute heart of America’s Great Plains.

Today, not much of civilization exists in the region. Most towns on the map are too small to have their population listed in back of the atlas. Some are abandoned. Some show only faint signs of life. Even the largest enclaves, boasting populations of two or three thousand, feel isolated and lonely.

Near larger centers of humanity, cows can be seen in pasture and green belts of crops indicate occasional farms. But White settlement seems feeble when compared to the vastness of the prairie pressing against its borders.

Life moves with the solemn trudge of futureless routine.

As it did when the first pioneers ventured into the region, White civilization gives the impression it is clinging to the land.

And it is.

For generations, America’s Great Plains have been emptying out. The promise of cattle living off oceans of grass has never been fulfilled. Nor has the boundless harvest of agriculture. Business is static. Every year there are fewer children, fewer schools, fewer homes.

It’s as if the supernatural void of earth and sky is gradually reasserting a dominance it never really lost. The dominance was only temporarily obscured by the agonizing cultural shuffle that took place one hundred fifty years ago, a bloody and numbingly tragic shift that changed the furniture of the place forever.

But the foundation of creation is still there. The incessant wind, the rolling prairie, the cloud world above, and the green tinted veins of water that pattern the landscape are all intact.

It is quiet now, but one hundred fifty years ago it was a very busy place, brimming with daily life-and-death exertions for survival among a people who saw themselves not as superior, but as part of the whole.

Ever-shifting rivers of buffalo streamed over the open prairies of Kansas and Colorado, a free-moving force of nature from which came the center of balance for the teeming life that surrounded them.

By 1868, however, a wave of invasion was coming, a wave that grew too fast for its height or length to be gauged by those who watched it flood over the Plains.

Whether the wave would be defeated was not an issue. It was destructive. It was everywhere. It could not be cajoled or begged or treated. It had to be fought.

The gut of the Great Plains that comprises the Kansas/Colorado border is peppered with historic sites from that time of upheaval. Some have been given designating markers by the state. Some require hikes. Some remain mysteries

The most famous spot in the region lies forty minutes north of a stockyard town. People rarely visit because hardly any Americans know where it is, what meaning it carries, or even what it is called.

The site lies along the banks of a shallow, slow-moving stream called the Arickaree. The empty prairie slopes gradually downward on approach, bringing the traveler in sight of a lovely, green line of large and numerous cottonwood trees. They cast their shade over a few acres of rich grass next to the winding Arickaree with its clusters of bushes and reeds growing wild at its banks and on its oldest sandbars.

The place is designated a state park and lies just off a deserted two-lane road. It is possible to spend hours in the park without seeing or hearing another vehicle, which discourages all but the most adventurous and imaginative visitors who, driven by historical intrigue, position themselves for beauty and haunting.

Those who know it call the spot on the river Beecher Island, a name of irony in that it no longer exists, the forces of drought and flood having long ago rearranged or obliterated it.

The park has no information center, only picnic tables scattered under the trees. A marker etched with a few paragraphs of text informs the public of what happened where they are now standing:

In September of 1868 a group of fifty civilian “scouts” under the command of Major George Forsyth engaged hundreds of Northern Cheyenne, Sioux, and Arapahoe at this site. The Americans, trapped on a sandy island, repelled multiple assaults until, after four days, the Indians withdrew.

A relief party reached the scene and rescued the survivors. Lieutenant Frederick Beecher, second in command, was one of those killed during the siege and the conflict was named after him.

But there is far more to it than that. The words on the marker, literally set in stone, are typically one-sided and self-serving, offering a rendition of history that promotes false senses of pride, honor, and satisfaction that, instead of enlightening the public, only perpetuates its ignorance.

Evidence of this is everywhere and is no more prominently displayed than in the title: Beecher Island. Naming a conflict after an individual promotes the presumption that there was something special about the namesake’s actions.

It would be natural to assume that the young lieutenant died in hand-to-hand combat, or sacrificed himself to save the group, or took an arrow in the chest dragging a bag of ammunition back to the front lines.

But nothing like that happened to Lieutenant Beecher. No doubt he was a dedicated and enthusiastic young officer. He had been on the frontier long enough to know his way around, but his time in uniform was too brief to achieve distinction.

The sole, distinguishing aspect of his participation at the Battle of Beecher Island is that he died during the enemy’s first pass. Whether it was with guns blazing is unknown. It is plausible that he never knew what hit him. All anyone knows for sure is that after the enemy’s initial, chaotic assault, Lieutenant Beecher was dead on the ground.

Why then was a fight that has been recounted hundreds of times in recorded history named after him? The answer lies, not in what he did, but in who he was. The lieutenant’s uncle was the nationally known scholar, teacher, and writer Henry Ward Beecher; naming the battle after his nephew conveniently served the long-standing American appetite for celebrity over substance.

The fight at Beecher Island has long been celebrated as a shining example of American determination and bravery in the face of savage, overwhelming odds. But for the Whites, Beecher Island was not so much a battle as it was a humiliating ordeal that should have ended in death for Major Forsyth and his entire command. In fact, anyone who takes the time to peek under the veneer of the battle will discover that the entire foray was naïve and grossly ill-conceived. Driven by a political desire to assuage public fear, the Battle of Beecher Island never should have happened. While it is connected to a long string of conflicts that, in the quick span of fifty years, brought about the displacement and subjugation of dozens of nations, Beecher Island stands today as a colorful curiosity rather than a turning point in American military history.

For the Cheyenne and their allies, however, the battle had profound, enduring consequences.

In terms of victory or defeat, the fact that they were unable to wipe out an enemy they outnumbered by more than ten to one was frustrating, but not devastating. The Indians of the Plains were seasoned in the vagaries of lethal contests. Outcomes were always delicate, and something so simple as a shifting of the breeze could turn certain victory into abject failure and vice versa.

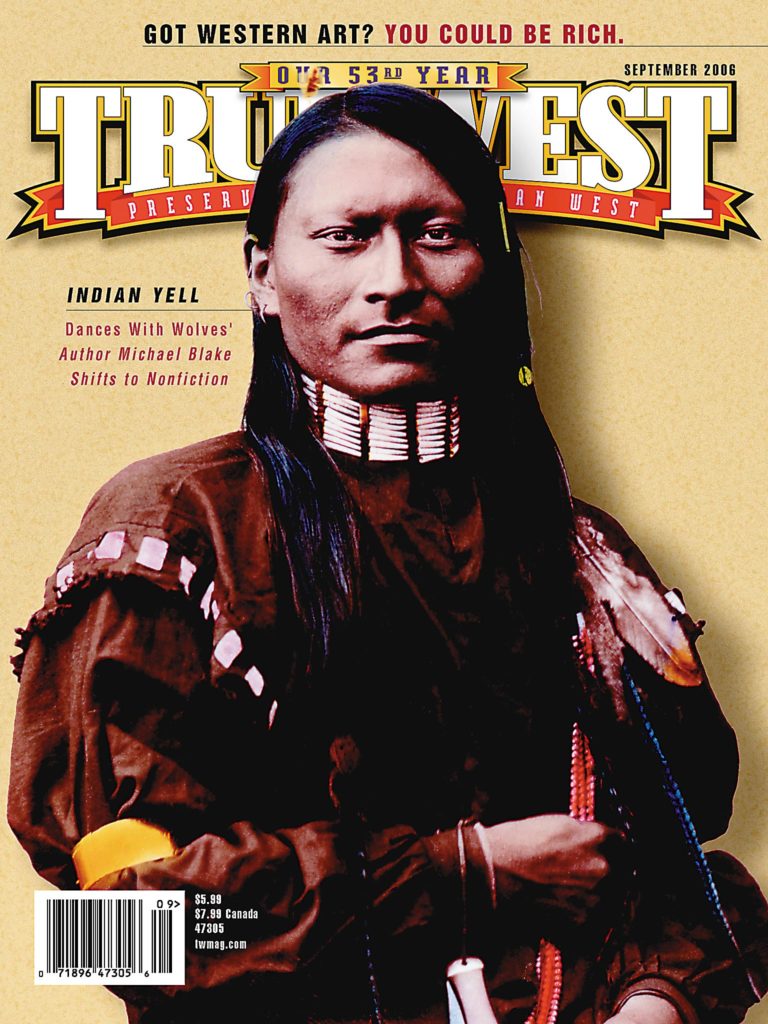

The warriors who fought Forsyth and his scouts on the Arickaree would, in years to come, fight on in hope of somehow stemming the White tide. But after Beecher Island they would go into battle without a man whose influence, power, and skill were so revered that many regarded him as a living icon. What his precise name was or how it was pronounced is not known.

History calls him Roman Nose.

His rise as a warrior is unchronicled, but there are absolutes that came with his ascendance. Being born in the wild and making it to teenage years was no mean accomplishment in itself. The majority of young men aspired to be warriors, but recklessness and inexperience killed inordinate numbers. Roman Nose was not among them.

Indian society was not bereft of politics. Those born to rich or prominent families enjoyed advantages from birth, and manipulating greater influence through arranged marriages and other maneuvers were commonplace. But political power held no appeal for Roman Nose. He focused entirely on warriorhood as his chosen endeavor, a field that, unlike White society, was immune to bribery, corruption, or deceit. In the world of warriors all was earned in the pure forum of the battlefield. Leaders qualified for greatness by meeting two simple criteria. They won and they survived.

Roman Nose did both.

In the years before Beecher Island he earned elite status by participating in a long string of important battles against Whites on the northern Plains, often in concert with Sioux allies. By the time the southern Plains became imperiled by White inroads, Roman Nose had gained supreme status as a war leader. His words in council carried tremendous weight and his every move was monitored. Hundreds, even thousands of Cheyenne warriors and counterparts in other tribes clamored to follow wherever he led.

By the summer of 1868 White settlement and the tentacles of the railroad had prompted increasingly aggressive reactions on the part of Roman Nose and his comrades. But it was not the roar of locomotives and the establishment of White society that troubled the Cheyenne the most. It was what transport and settlement brought with it to the southern Plains that lit the fuse of war—the flagrant, malicious genocide of the buffalo.

In the year before Beecher Island, organized hunting parties had sallied onto the prairie in large numbers, killing buffalo until their ammunition was exhausted, taking with them only hides and tongues. Rail passengers were encouraged to shoot from their windows for no other reason than to see the animals die or wander off disabled. Soldiers shot them for sport, and by mid-1868, trains filled with day hunters were traveling back and forth across Kansas.

To see animals slain in a fashion that spits on the sanctity of life, to see them staggering crippled across the prairies, and to see their intact carcasses swelling under the sun for nothing would surely create outrage in people other than Indians. But it is difficult to imagine how the Cheyenne, like many other free-roamers, must have felt. The buffalo were not simply their physical salvation. The buffalo were relatives.

Fed up as the slaughter escalated, the Cheyenne of Roman Nose began to raid in dead earnest. They attacked stages and troops and occasionally trains. But the bulk of their wrath targeted the most vulnerable members of the gigantic White incursion: the settlers who hugged the region’s waterways hoping to distill a living from the land.

Roman Nose led many raids along the Solomon and Saline rivers that summer of 1868, burning and killing with impunity. No White family was safe from Indian rage.

Military authority reacted by issuing orders that recalcitrant Indians were to be herded south in order to position them for incarceration on designated reservations.

The sweeping dictate immediately placed the commander of the enormous region occupied by the “hostiles” in a tight quandary. The army had been reduced to comparatively nothing following the Civil War, and the already skimpy number of troops at his disposal was tied up manning garrisons, guarding rail lines, and escorting wagon trains. Still the order had to be executed.

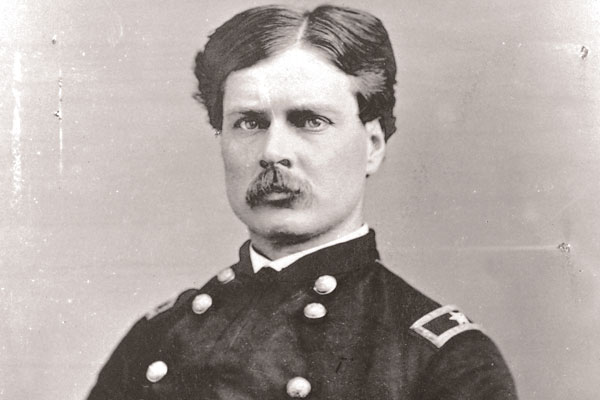

How he could have expected the scheme he devised to accomplish anything is not a matter of public record. Major Forsyth and Lieutenant Beecher were instructed to hire and command a force of “fifty first-class hardy frontiersmen to be used as scouts against the hostile Indians.”

In both counts what hatched was ludicrous.

“First-class, hardy frontiersmen” were a myth. The majority of those who hung around the military then were career spongers, opportunistic businessmen, and criminals.

And how could fifty men “be used as scouts” to herd whole, highly-fluid nations anywhere?

Major Forsyth, a learned soldier known for toughness, recruited his fifty men and set out for “Indian country” unencumbered by wagons, tents, or cannon and outfitted with little in the way of rations.

Hoping to strike the trail of a war party, the contingent instead happened onto a much larger track, indicating a village on the move.

In a time-honored tactic of evasion, the Indians had split into smaller and smaller groups as they spread over the country. The scouts split too, sticking to a number

of trails until, at last, their quarry reconverged.

The trail was now bigger than ever, and a number of scouts expressed concern that they might be biting off more than they could chew.

Forsyth countered the anxiety by reminding his force that they had been recruited to fight Indians. Otherwise, what were they doing out here? The issue did not come up again and even if it had, it would have been too late.

Why did Forsyth insist on following what was obviously a huge force with his tiny detachment? Contempt for the enemy is practically a prerequisite for opposing factions in warfare, and both Indian and White harbored plenty of disdain for one another.

But on the White side, contempt bled into a wider condemnation. Indians were widely perceived by settlers, government figures, and the military as being more animal than human. In parlays their speech was guttural, they ate with their hands, they cared nothing for money, dressed like the wild creatures they were, and in war were so disorganized that, faced with superior weaponry, they were easily scattered.

This attitude, based almost wholly on ignorance, was endemic in military circles and it was widely agreed that defeating Indians wasn’t the difficulty. Catching them was the hard part.

Forsyth was an educated, former businessman who had seen plenty of action in the war between the states. By any measurement he was at least competent. Yet he subscribed to the prevailing attitude that, once found, Indians would be defeated. Odds didn’t really matter.

There is no way to exaggerate the concrete quality of these perceptions

held by Forsyth and most of his contemporaries. Regardless of how much knowledge was obtained about Indian life, in most minds, they remained sub-human. And no matter how many defeats American troops suffered at the hands of Indians, White arrogance never diminished.

On an afternoon in mid-September, Forsyth’s command crossed from Kansas into what is now Colorado and set up camp on the grassy banks of the shallow, slow-moving Arickaree. Fortunately, they chose a site fronting a small, sandbar island, perhaps fifty feet wide by three hundred long and covered with old growth, reeds, and bushes.

Unbeknownst to them, the Indians they were following had also set up camp only a few miles downstream. They had known for days that they were being followed and by whom, and they had now decided to swoop down at dawn and kill their pursuers.

The village, consisting of several tribes and many bands, was huge by standards, and socializing was intense. Roman Nose himself had dropped in on a Sioux friend and shared food just prior to going into battle. After eating, he learned that his friend’s wife had used a metal utensil in preparing the food. Such a procedure was strictly taboo, for it rendered valueless the personal medicine that Roman Nose depended on for survival in combat. Ceremonies of considerable preparation and indeterminate length would have to be conducted to right the error.

But there was no time for that, and Roman Nose, to the doubtless consternation of his followers, had no choice but to sit the battle out.

Forsyth’s sentries reported the advance of the enemy, stating there were hundreds of them, and the commander made a quick decision that saved many lives. They needed a redoubt, and the only thing that might serve as one was the tiny island in the middle of the stream.

Dragging their horses and ammunition with them, the scouts made it onto the island just as their attackers came into view. The thunderous mass of riders bore straight down on the island.

The scouts opened fire with repeating rifles and pistols, far more sophisticated weaponry than their foes possessed and, while their concerted explosion of lead did not blunt the charge, the shower of bullets from the island was able to split it.

Warriors, with the exception of a few daring men who rode over the scouts, blew past the island in two streams, hanging from the sides of their horses as they fired.

Several scouts were killed on the first pass including Lieutenant Beecher. The unit’s doctor was shot in the head and never regained consciousness. Major Forsyth took three bullets. One bounced off his head, leaving a permanent dent in his skull. The other two hit each of his legs. Despite his injuries, the major didn’t pass out and somehow maintained command over the next four days, even going so far as to perform surgery on himself to remove a lead ball that had damaged a nerve in one of his legs.

Almost half of the scouts were disabled to some degree after the first charge, and the enemy was not going anywhere. Many warriors were taking up positions around either shore while the bulk of the fighters began to mass for another horseback assault.

Under fire from every direction, the scouts frantically dug out pits in the sand with knives, belts, and bare hands and, once settled in, took no more casualties.

The Cheyenne and their allies had lost roughly the same in dead and wounded.

As always, the greatest casualties were inflicted on the horses of both sides. They were instantly marked for death, and by the end of the first hour of fighting all of Forsyth’s animals were dead. The scouts couldn’t move the animals that now blanketed the tiny island. Nor did they want to at first since the cover the corpses provided was essential to the survival of many. But as the day moved on, the dead began to bloat, and then to stink.

The scouts’ attackers made several more charges that day without inflicting much damage. The Whites were well dug into the island, had ample ammunition, and were not going to make themselves vulnerable by running. A stalemate was building.

There was no letdown after the first assault. Hundreds of warriors continued to pour fire onto the island in hopes of killing or routing the enemy.

Neither would be accomplished, and as the day wore on, the warriors’ enthusiasm began to wane. In continuing to attack an entrenched enemy, more casualties were inevitable, and a contest of attrition was not feasible. A seasoned warrior took a generation to replace; desperate as they were to repel the Whites, cost was a huge consideration. Engaging in fights only took place when odds for victory were high, and if a battle went poorly there was no dishonor in withdrawing.

At Beecher Island the odds were dropping with the sun, and by late afternoon, several disenchanted warriors rode off to find Roman Nose. He was not in camp but behind a hill near the battleground where he had sequestered himself for most of the day.

When the warriors confronted him, one openly challenged the great warrior to intervene on behalf of his brothers-in-arms, who were suffering. Whether he was moved by this challenge specifically is not known. Roman Nose’s physique (he was more than six feet tall and well proportioned) was a good reflection of his immovable mentality, and it seems unlikely that the pleas of a single man or even a delegation could have pushed him. But the beseeching of that afternoon probably had the effect of a last chop at a tree that needed only one more to fall.His agony over not being able to enter the fight must have grown as the day progressed. The unsuccessful charges he was hearing about would have vexed a man of Roman Nose’s caliber. To his mind, strong leadership would have produced a different result. He could have provided that.

In a deeper, more personal way, sitting out the fight would have grated on him as a missed opportunity. To die in bed or by accident on a hunt was a warrior’s constant nightmare. Dying on the battlefield attained what could be gotten by no other means … eternal satisfaction. It was every warrior’s dream, and despite his unique status, Roman Nose was like any other warrior when it came to that particular dream.

When he was confronted behind the hill, Roman Nose made no verbal response. He turned away and began to apply paint to his face. He lifted a bonnet of feathers and horns to his head, the same bonnet he had worn through all his fierce battles. He rode down to his fellow warriors and said he would now lead them. In the last charge, as had always been his practice, Roman Nose galloped yards in front of his followers.

When he reached the island he rode over an ambuscade manned by several scouts. One of them popped up and shot him in the back, the bullet entering his spine below the hips.

Roman Nose was carried back to the temporary village where he refused medical help, purportedly saying that while death was not a problem, he didn’t want to live like he was now, paralyzed from the waist down. He died that night.

The next morning his wife and others took the body far out on the prairie, erected a scaffold, and placed his corpse on top.

The same night Roman Nose died, Major Forsyth called for volunteers and sent two men into the night, hoping they could slip past the enemy unscathed and somehow reach help. It was a long shot he had to take, but without help they were all sure to die.

The scouts chosen to somehow break out and secure aid turned out to be good picks. One was a wily man of late middle age, the other a savvy teenager. Removing their boots, the two walked backward off the island and succeeded in passing through the Indian line undetected. They escaped death at the hands of a war party by hiding under the rib cage of a decomposing buffalo and, miraculously, reached a stage station and then the nearest military post where relief parties were hastily organized and sent out.

No more charges were made against Beecher Island, but the Cheyenne and their friends did not let the scouts off easily, firing persistently at the island through all of the next days. By the third day, however, far fewer Indians were seen and sniping was sporadic. On the fourth day the scouts didn’t see anybody but there was nothing they could do. They had no food, no transportation, and a score of groaning wounded they couldn’t leave.

On the morning of their ninth day on the island, a cavalry unit came to the rescue and, except for a scout who died after his leg was amputated, all were saved.

News of the Beecher Island ordeal spread nationally and was celebrated publicly as a chest-thumping triumph

of American tenacity and “supernatural bravery.” Christian righteousness had emerged victorious in a battle against barbarism.

Major Forsyth became a significant celebrity. Though he endured headaches for the rest of his life, he was walking normally within a year and finished out a long and distinguished army career enveloped in an iconic glow provided by Beecher Island.

As usual, Indian casualties rose as the story was repeated, helping cement the idea that the clash was a devastating defeat for the Indians.

It was and it was not.

Fewer than ten warriors had been killed, and the tribes had left the battleground because none of the glory and honor that were the rewards of war could be gained by maintaining a siege.

Starving an enemy to death had no appeal. The result of warfare was important, but individual conduct in warfare was what really mattered, and the Whites on the island were no longer worth the trouble.

The Cheyenne continued the fight to preserve their way of life for several more years, but the loss of Roman Nose had a long-lasting impact. People living free on the Plains received the blow of death routinely, and once a person was gone their name was no longer spoken, perhaps as a technique to help govern grief. Roman Nose was no exception. His name was no longer uttered; his ponies were placed with him on the prairie, and the material possessions of his life were piled next to the body on the scaffold.

But he took with him more than himself and the trappings of his life. The inspiration for a nation went with him.

In the future, many warriors would perform great deeds of sacrifice and survival for the common good, but none would ever exceed the magnificence of Roman Nose.

The great man who died at Beecher Island ended up like most distinguished Indian leaders—turning back to dust on the Plains. Like the others, unnamed and unremembered, he fell trying to preserve the only life he knew.

Did he have descendants and, if so, where could they be now? No one knows. But, if placing a wager were appropriate, it would be a good bet that the blood of Roman Nose runs yet in human form somewhere on the Great Plains.

For decades, White population on the prairies has been shrinking, and continues to wither. American Indian numbers continue to grow.

Perhaps it is all coming full circle. Perhaps nature will be allowed to restore some of what was destroyed. Perhaps there will come a day when a new monument will sit at the site called Beecher Island, a monument listing the names of warriors who died there, beginning with the man called Roman Nose.

Further Reading: Cheyenne Memories by John Stands In Timber, Yale University Press: 800-405-1619 / yalepress.yale.edu/yupbooks