The origins of scalping during warfare seem to originate hundreds, if not thousands of years ago in Europe and may have been practiced on this continent in pre-Columbian times, as well.

The act of scalping usually involved the partial removal of hair and scalp from the head of an adversary, sometimes leaving bare skull exposed in the process. In the Old West, the scalping of victims was practiced by cowboys, soldiers, settlers and Indians, sometimes when the victim was still alive. Such bad fortune certainly qualifies as a major cause of “Fear on the Frontier.”

Consider the story of Delos G. Sanbertson, recounted by a “former resident of Laramie [Wyoming Territory]” in The New York Times on July 5, 1889. Sanbertson, a soldier under Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer, was scalped at the Battle of Washita on November 27, 1868, and lived to tell the story:

While I lay in the snow with a gunshot-shattered left arm, “…the big Indian was determined to run the risk of getting my scalp…and he pounced down on me, with his knees on my chest, drew his knife, and the next second, although it seemed hours to me, the top of my head was in his hand, and he was gone.”

Sanbertson continued: “Imagine someone who hates you with the utmost intensity…suddenly grabbing a handful of your hair, while you are lying prostrate and helpless, and giving it a quick, upward jerk with force enough almost to loosen the scalp; then, while this painful tension is not relaxed imagine the not-particularly-sharp blade of a knife being run quickly in a circle around your scalp, with a sawing-like motion. Then let your imagination grasp, if it can, the effect that a strong, quick jerk on the tuft of hair to release the scalp from any clinging particles of flesh that may still hold it in place would have on your nerves and physical system, and you will have an inkling of how it feels to be scalped…. When the Indian tore my scalp from my head it seemed as if it must have been connected with cords to every part of my body. The pain that followed the cutting around the scalp had been frightful, but it was ecstasy compared to the torture that followed the tearing of it from my head.”

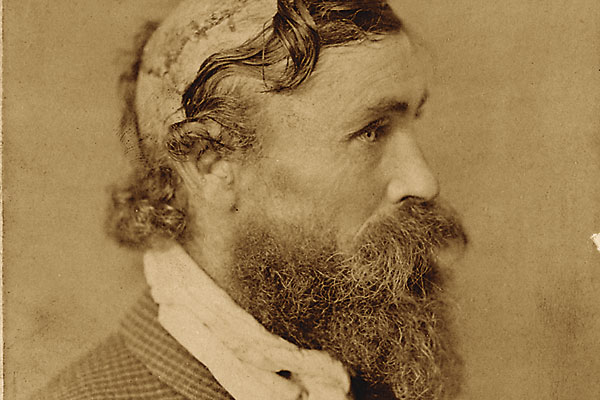

The former Laramie resident continued with his tale: “Sanbertson lay for weeks in the Government Hospital at Fort Laramie perfectly helpless and suffering untold agony. He finally recovered, and in the meantime his term of enlistment expired.”

“…all the nursing I got haint made the hair grow out on this spot yet,” said Sanbertson, in his account published the summer after the fight, in the July 2, 1869, Emporia News in Kansas.

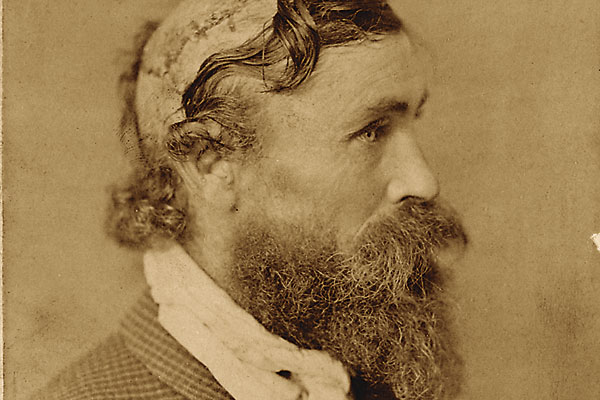

“I saw Sanbertson several years afterward,” the former Laramie resident said, “and the same pale-red, flat, round, bare spot was on top of his head, showing where his scalp had been torn away, as I had seen it when he left the hospital. He said that it was extremely tender, and in damp or cold weather was very painful.”

As a young physician, I learned something special about scalp wounds; they bleed more than you can imagine. You can be fooled by the persistent, often pulsating bleeding of a small wound or correctly impressed by the massive, bloody gushing of a clinically significant scalp injury. The skin of the scalp is full of many blood vessels that are necessary to nourish the thousands of hair follicles on top of the head. When disrupted by a laceration or avulsion (tearing), these vessels bleed profusely.

I once treated a girl who had been scalped after her long hair had been caught in a rapidly spinning metal lathe. She was nearly unconscious from the pain. At least I had the avulsed scalp to re-cover her wound with a couple of hundred sutures. She recovered, with no complications, full of antibiotics and a tetanus shot, but, for safety, with the temporary hairdo of a marine recruit.

Today, Sanbertson, absent his scalp as a Cheyenne trophy, would be treated with a skin graft taken from his own body that would provide closure for the bare spot on top of his head. Until medicated, like my patient, however, poor Sanbertson’s pain would have been the same.