Back in the 1980s, LIFE magazine quoted an American Automobile Association representative regarding the 260-mile segment of Highway 50 that meanders across central Nevada between Ely and Fallon: “It’s totally empty. There are no points of interest. We don’t recommend it.”

Well…horse feathers.

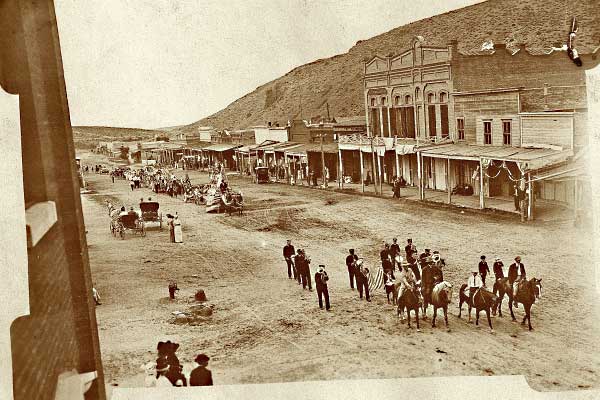

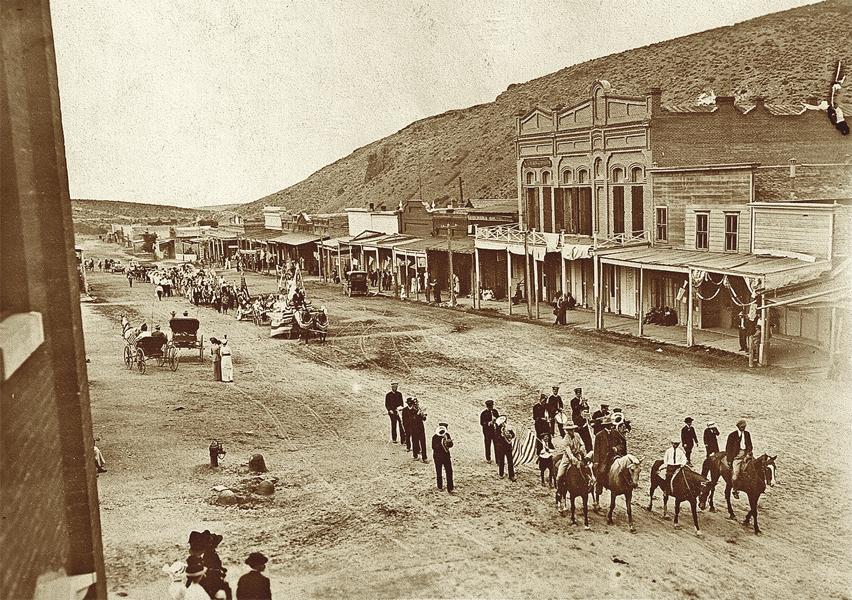

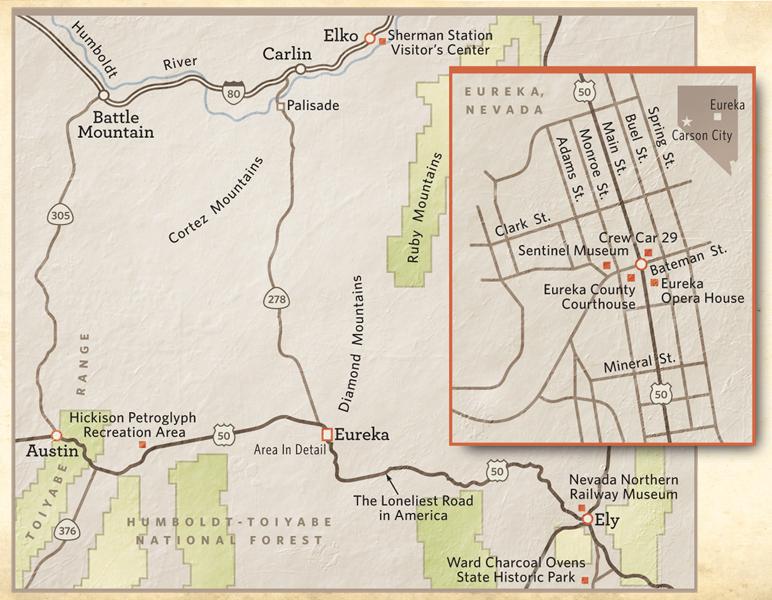

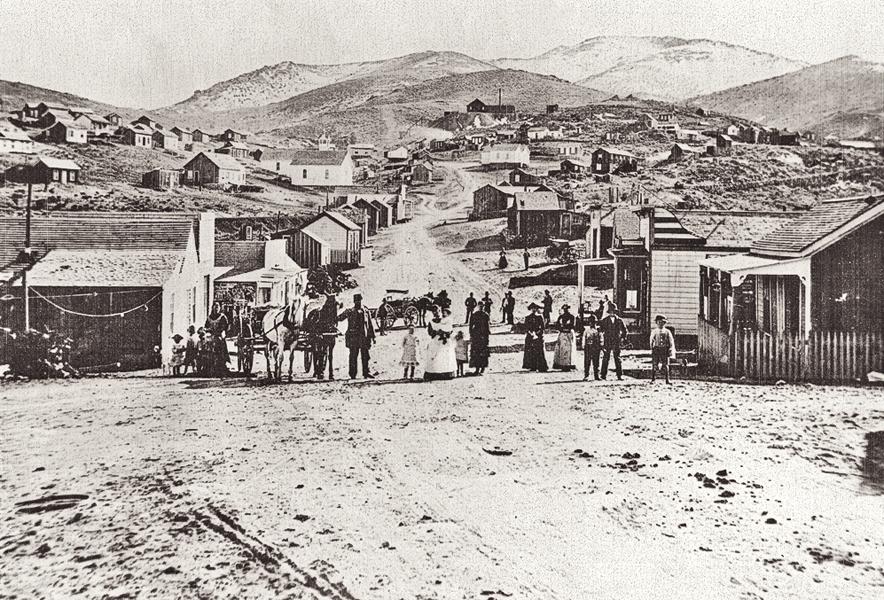

Eureka, which straddles that lonesome highway some 75 miles west of Ely, is one of the best-preserved old mining towns in Nevada. Dozens of structures built in the 1880s and 1890s are still standing, many of them still in use. Besides that, driving the so-called “loneliest highway in America” is a treat in and of itself—especially for historically minded travelers. “It’s a great way to experience the wide open beauty of Nevada,” says Andrea Rossman, Eureka’s Cultural, Tourism and Economic Development director. “The country looks the same as it did in the 1800s.”

Nowadays the town’s isolation actually attracts new residents looking for a little peace and quiet, Rossman says. “Our remoteness is one of the blessings of living here.”

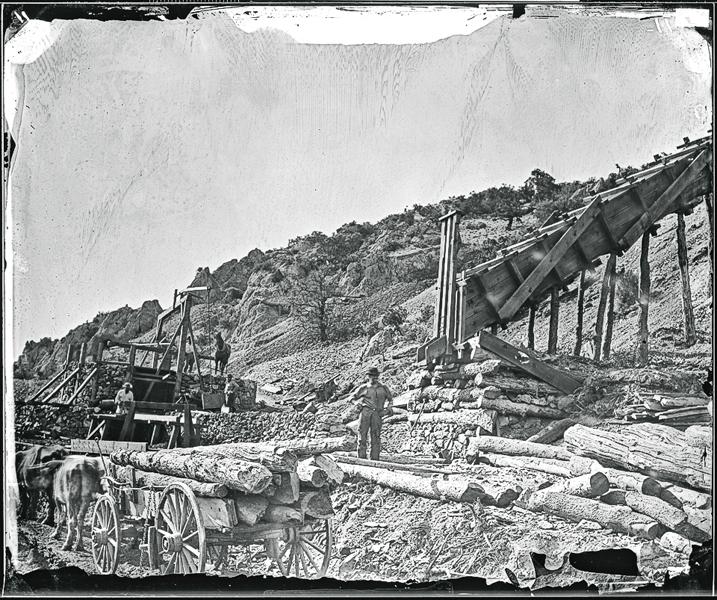

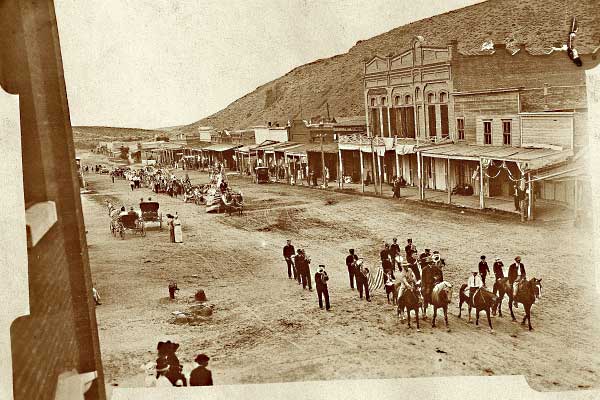

Silver ore drew the first prospectors to the area in 1864. The town was established in 1865, but didn’t really take off until mine operators started building smelters there in 1869. By 1878, the town’s population approached 10,000 people, making Eureka the second-largest city in Nevada. (Apparently, mining was thirsty work; at one time the town had 125 saloons.) For a while, Eureka became one of the country’s largest producers of lead, says Rossman. And its 16 smelters, which could process more than 700 tons of ore a day, belched out so much heavy smoke that the town became known as the “Pittsburgh of the West.”

While some Old West towns feuded over water rights or fought bloody range wars, the big battle in Eureka was over charcoal, a necessity for the town’s many smelters. In July 1879, around 500 charcoal makers—most of them Italian immigrants—formed the Charcoal Burners Protective Association and tried

to raise the price of charcoal from 28 cents a bushel to 30 cents. Within a month, though, a posse confronted a group of charcoal burners. When the shooting stopped, five charcoal makers lay dead, with several others wounded. Afterwards, smelter operators informed the Association that henceforth the price of charcoal would be 26 cents a bushel.

By 1891, most of the major mines had closed and the population began to dwindle.

Ree Taylor, a longtime Eureka resident and the manager of the Sentinel Museum, recommends a self-guided walking tour as the best way to take in the town’s history. One of the highlights is the Sentinel Museum itself, housed in the 1879 Eureka Sentinel Newspaper Building. Along with a pressroom filled with original 19th- and early 20th-century equipment, the museum holds information on mining and daily life in the Old West.

The Eureka Opera House was built in 1880 on the site of the old Odd Fellows Hall, one of many buildings destroyed in the town’s great fire of 1879. Originallythe Opera House hosted plays, concerts, dances and masquerade balls; later on it became a movie theater. It underwent an extensive renovation in the early 1990s and now serves as the town’s Cultural Arts Center.

Eureka’s courthouse was built in 1879, Rossman says. It, too, has been renovated, but in a way that “kept its historical integrity, so it still looks very much the same as it did when it was built.” It is one of only two 19th-century Nevada courthouses still in use.

Other points of interest include several historical churches, five cemeteries and Crew Car 29, used on the narrow-gauge Eureka & Palisade Railroad, which operated from 1875 to 1938.

John Stanley was a longtime newspaper travel writer and photographer in Arizona.

Photo Gallery

– Lee Raine/CowboyShowcase.com –

– Courtesy Paula Peper –

– Courtesy Dean Reynolds/Eureka County EDP –

– By Timothy O’Sullivan, Courtesy National Archives, Photo No. 106-WB-11 –

– Courtesy Connie Hicks –

– Lee Raine/CowboyShowcase.com –

– Lee Raine/CowboyShowcase.com –