The American West was vast, lonely and wild. Railroads made it a little less so for travelers, but for the engineers and their crews, the building of the North American railways was among the most dangerous and adventurous engineering feats in history.

The American West was vast, lonely and wild. Railroads made it a little less so for travelers, but for the engineers and their crews, the building of the North American railways was among the most dangerous and adventurous engineering feats in history.

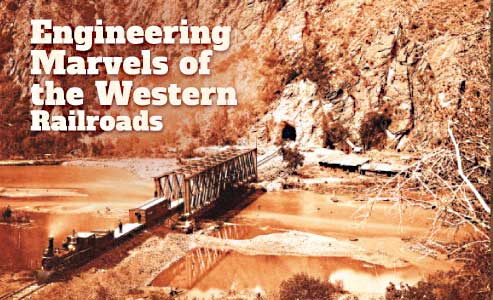

In the 19th century, distance could be a mortal enemy—not just to life and limb, but to commerce and development. Until the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869, a journey from New York to San Francisco was a perilous months-long undertaking. When steel rails at last met at Promontory Point, Utah, that journey was cut to a week, more or less, and threats of death on the long and dangerous cross-country trails were greatly reduced. By the early 20th century, rail lines spider-webbed the country, pushing up deep gorges and boring through towering mountain ranges, delivering prosperity to a bourgeoning nation. But progress wasn’t easy, with dangers waiting around every curve. Travel along as True West explores some of the engineering marvels of the American West.

Summit Tunnel Donner Pass/CA•1867

The Sierra Nevada’s granite heart was conquered to connect a nation.

Harsh winter snows and solid rock tried to stop the Central Pacific in its tracks, until engineers found a way to keep the rails moving forward to build Tunnel No. 6, otherwise known as the Summit Tunnel through the Sierra Nevada. Chiseled out inch by inch, and never more than two feet per day, the No. 6 was bored through 1,659 feet of solid granite by Chinese laborers, many of whom lost their lives to accidental explosions, falling rocks and winter avalanches.

Construction began on each end of the tunnel in August of 1866. By the end of the month, engineers ordered a vertical shaft be dug down from the top so crews could work from four faces, rather than two. When the passageway was finally completed in August of 1867, engineers’ calculations had been so precise that the four tunnels—two boring inward from east and west, and two moving outward from the center—were off by less than two inches.

Dale Creek Bridge Laramie Mountains/WY•1868

The trestle over Dale Creek was both thrilling and terrifying.

The Dale Creek Bridge, just east of Laramie, Wyoming, sat very near the highest elevation along the Union Pacific line—8,247-foot Sherman Pass. Towering more than 15 stories above the stony bed of Dale Creek, the wooden trestle was also the highest bridge on the transcontinental railroad between Omaha and Sacramento. Construction began in December 1867, and the first train crossed on April 23 the following year. Although considered one of the most dangerous bridges on the entire line—trains were forced to creep across the 720-foot-long structure at no more than four miles per hour—it wasn’t engineering errors that concerned crews and passengers, but the prevailing strong winds near the summit that caused the structure to sway noticeably, and could tumble even boxcars into the rocky chasm below. As passenger Ellen White wrote in 1873, the “trestle looks like a light, frail thing to bear so great a weight. But fears are not expressed because of the frail appearance… but in regard to the tempest of wind, so fierce that we fear the cars may be blown from the track.”

Cumbres & ToltecAntonito, CO/ NM•1880

Silver brought the railroad; the Rockies keeps the locomotives running year-round today.

Between the 10,015-foot Cumbres Pass and the 800-foot-deep Toltec Gorge, the Cumbres & Toltec faced its fair share of hurdles during construction, despite the fact that railroad president William Jackson Palmer called it “a little railroad, a few hundred miles in length.” One of the biggest challenges after completion was snow, as much as 40 feet of it per year. The Cumbres & Toltec is the highest operating adhesion railroad in the country, and 19th-century plows and rotaries couldn’t stay ahead of the drifts. The answer: snow sheds, strategically located manmade tunnels built to withstand winter’s heavy accumulations. The C&T used numerous snow sheds to keep its trains running, including a large one over its turning wye. Today, more powerful blowers keep the tracks clear for year-round operation, but the remnants of one of the larger snow sheds can still be seen along the C&T route, a reminder of what it once took to keep trains running.

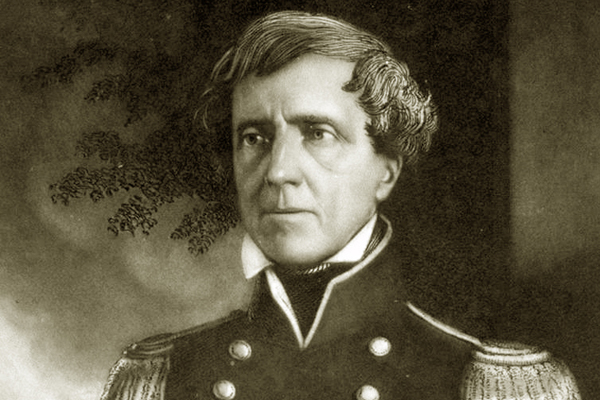

Diablo Canyon/Flagstaff, AZ•1882

Railroad engineers bet they could bedazzle Devil’s Gorge with a pre-fab bridge—and they lost.

Nearly two decades before Engineer Lewis Kingman faced the challenge of bridging Devil’s Canyon, Lt. Amiel Whipple of the Corps of Topographical Engineers, reported “we were all surprised to find at our feet…a chasm probably one hundred feet in depth, the sides precipitous, and about three hundred feet across at the top.” Kingman’s plan was to have the bridge built off-site for the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad, but the designs were apparently misread, and the preassembled sections ended up being several feet too short, bringing the railroad to an abrupt halt on the very lip of the gorge. While a new bridge was being constructed in the east, work continued as best it could. Limestone pillars for the bridge’s bases were excavated from nearby deposits and chiseled into shape by Italian stonemasons. When the reconstructed bridge was finally delivered and assembled seven months later, the bridge stood 220 feet above the canyon floor and stretched for 544 feet from one side to the other. If not for someone’s earlier miscalculation and long delay, the bridge’s prefabricated construction might have been a feat to celebrate; sadly, it’s doubtful that any champagne was uncorked.

Durango & Silverton Railroad/Durango, CO • 1882

The Durango & Silverton Railroad is an engineering wonder 400 feet above the Animas River.

In 1909, George Lawton reflected in the Telegraph Age about the sacrifice of human lives to build rail lines in Colorado. “The expense is great, and the loss of life in blasting through the solid masonry of the Rocky Mountains, has left many an unmarked and unknown grave.” When it comes to feats of engineering, it’s pretty hard to top the Denver and Rio Grande’s line from Durango to Silverton, in southwestern Colorado. It’s a 45-mile climb up Animas Canyon, and the route often seems as if it’s been carved straight from the face of the cliff, which in numerous places it was. Many men lost their lives falling into the canyon below. The Durango & Silverton was an extension of the Cumbres & Toltec Railroad, out of Antonito, Colorado, built to haul silver and other precious metals out of the San Juan Mountains. The raw ore was then delivered to smelters in Durango, founded in August of 1881 by the D&RG as a railroad terminus. Despite the San Juans’ rugged terrain, the Durango & Silverton extension was completed in a scant 11 months, and a train has been rolling over those rails ever since.

Georgetown Loop/Georgetown, CO•1884

The Colorado Central Railroad had just two miles to scale 640 feet.

Skeptics said it couldn’t be done; Union Pacific’s Jay Gould said it could. In the early 1880s, the race was on for the silver-rich mines surrounding Leadville, Colorado. The first railroad into town was almost guaranteed huge profits, and Jay Gould, of Union Pacific fame, wanted in. He’d already helped finance the Colorado Central Railroad from Denver to Georgetown, but to reach Leadville, he was going to have to push even deeper into Colorado’s high country. Gould’s first obstacle stood just outside of Georgetown, the two-mile stretch of canyon to Silver Plume. Although practically next door, Silver Plume rose nearly 640 feet higher in elevation, requiring grades far too steep for traditional rail traffic. Gould brought in Jacob Blickensderfer, his chief engineer from the UP. Blickensderfer’s proposals were a series of deep cuts, dirt fills, sharps turns, and, the star of the line, the Georgetown Loop. It took four and a half miles of track to span those two miles, plus the trestle that made Georgetown famous, towering 95 feet off the ground before curving back toward the Divide. The result? The Denver and Rio Grande reached Leadville while the Colorado Central was still struggling up the canyon past Silver Plume. With the grand prize snagged by the competition, Gould pulled out, and the rails ended abruptly just west of Silver Plume.

Pecos River Viaduct/Langtry, TX • 1892

Langtry, Texas, is Judge Roy Bean country; that made it handy when a coroner was needed for construction accidents.

Texas author J. Frank Dobie wrote that “the lower reaches of the Pecos canyon have been cut through solid rock and are deep and impassable.” And impossible is just the kind of challenge American railroad engineers had to overcome when they built the Pecos River Viaduct in 1892. Known today as the High Bridge, the second rail trestle to span the Pecos River was 321 feet above the distant river below, and for a while, the highest bridge in the United States, and the third highest in the world. Being 2,180 feet from one rim to the other, it was no slouch in length, either. It was made of steel, more than 1,800 tons of the stuff, but by the end of the 19th century, most railroad trestles were. The viaduct was constructed by the Southern Pacific to avoid the longer route that hugged the Rio Grande to a crossing built in 1883. Although intimidating in size, the higher bridge shaved 11 miles and quite a few hours off the original route.

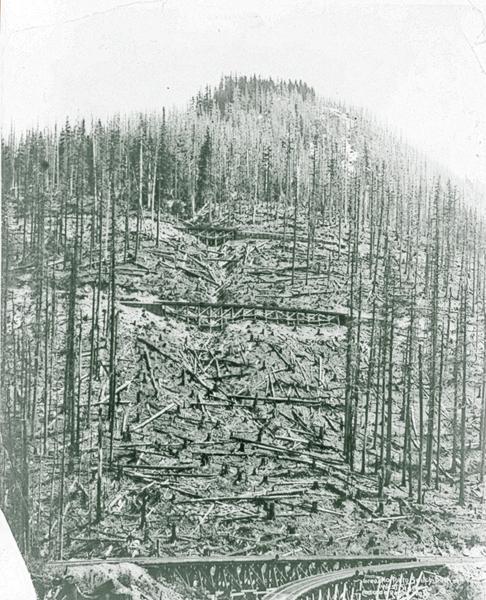

Stevens Pass/Skykomish, WA • 1893

Engineers’ amazing switchbacks lifted the Great Northern over the Cascades.

Legend has it that Great Northern Railroad’s CEO James J Hill boasted, “Give me snuff, whiskey and Swedes, and I will build a railroad to hell.” Hill’s switchbacks over the Cascade Mountains are a perfect example of that. Hill knew he’d eventually have to bore a passage under Stevens Pass, but tunnels take time, and Hill wanted to complete his railroad to Seattle as quickly as possible. The answer was a temporary route over 4,059-foot Stevens Pass that included 12 miles of switchbacks. In order to make the climb, trains had to be shortened to 1,000 feet in length. At each switchback, the line of cars would pull forward onto a stub, a workman would throw a switch, and the train would move backward to the next stub, continuing this zigzag pattern all the way over the top. Switchbacks were used until 1900, when the first tunnel was completed. Time saved: approximately two hours.

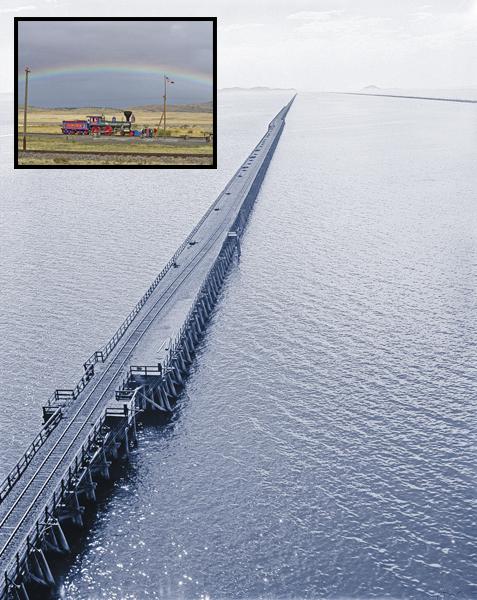

Lucin Cutoff/Ogden, UT • 1904

In 1869, the Southern Pacific shied away from the Great Salt Lake; in 1902, they tackled it head on.

By the turn of the 19th century, traffic over the old transcontinental rail line north of the Great Salt Lake had reached capacity, and engineers were looking for a solution. William Hood, the Southern Pacific’s chief engineer, thought he had it—build a route straight across the Lake to the west desert town of Lucin, Utah. It was a monumental task, requiring the use of 25 massive pile drivers, nearly 1,000 dump cars, 80 locomotives, and 3,000 laborers to finish the 102 miles of track. In places, the lake bed was so hard, steam jets were needed to blast out a pocket for a trestle’s base; elsewhere, mud reached depths of 50-plus feet, and fill dirt for the rail bed would often just sink from sight. But by the time the line was finished, 44 miles and 700 feet of grade had been shaved off the old route, saving the SP 20 hours and up to $60,000 per month.

Michael Zimmer is the author of fourteen novels, including The Poacher’s Daughter, winner of the 2015 Wrangler Award, and City of Rocks, a Booklist Top Ten Western for 2012

Photo Gallery

– Underwood & Underwood, Courtesy Library of Congress/ Verde Canyon Railroad –

The Central Colorado Railroad operated trains from Georgetown to Silver Plume from 1884 to 1938. Today, the historic Georgetown Loop Railroad, rebuilt between 1969 and 1987, shuttles riders across spectacular canyons.

– Courtesy Kyle Banister, Georgetown Loop Railroad –

– William Henry Jackson/Courtesy J. Paul Getty Museum/South Dakota Dept. of Tourism –

– Courtesy Yvonne Lashmett, Durango & Silverton Railroad –

Passengers on the Grapevine Vintage Railroad, the historic line between Grapevine, Texas, and the Fort Worth Stockyards enjoy “train robberies” every weekend between Memorial Day and Labor Day.

– Courtesy Grapevine Vintage Railroad –

– A.B. Wilse/Courtesy Library of Congress –

– Courtesy Skunk Train/Alfred A. Hart, Library of Congress –

– William Henry Jackson –

The Lucin Cutoff across the Great Salt Lake shortened the original transcontinental rail line, while the Jupiter (above) thrills visitors to the Golden Spike National Historic Site in Promontory Summit, Utah.

– Courtesy Library of Congress/NPS.gov –

Engineers drive Mt. Rainier Scenic Railroad’s historic locomotive No. 70, a Baldwin 70-ton built in 1922 for the logging industry.

– Courtesy Jeremy Echols/Mt. Rainer Scenic Railroad & Museum –

– William Henry Jackson/Courtesy Library of Congress –