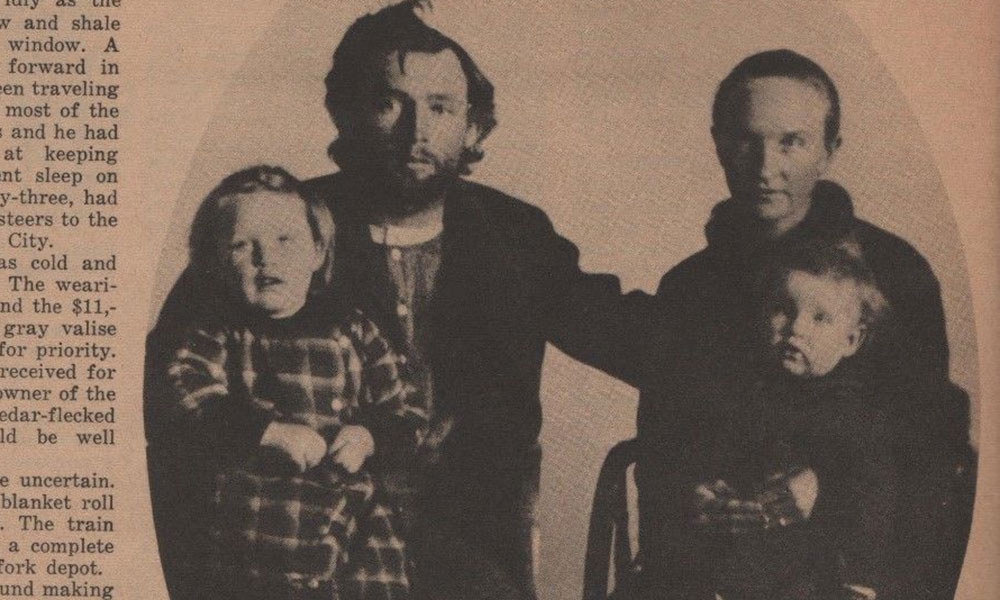

Children soothed their thirst by scraping their fingernails on barrack windows to capture frost and warded off hunger by chewing on leather. After four days of starvation, their elders declared they would rather die seeking freedom than perish like this.

Children soothed their thirst by scraping their fingernails on barrack windows to capture frost and warded off hunger by chewing on leather. After four days of starvation, their elders declared they would rather die seeking freedom than perish like this.

Thus, on January 9, 1879, Chief Dull Knife and approximately 149 of his Northern Cheyennes broke out of their Fort Robinson prison in Nebraska, successfully ending up on their homelands in Montana. They had been imprisoned at the fort since the first time they had fled, from the government-imposed exile of the tribe to Oklahoma.

Although unarmed, these refugees fought the U.S. troops who pursued them. Soldiers killed 39 Northern Cheyenne men and 22 women and children.

Journalists horrified the nation with accounts of the flight. President Rutherford B. Hayes called for a congressional investigation of the “unnecessary cruelty,” and The New York Times editorialized about the “shameful record” this incident added to America’s sins.

If the Northern Cheyennes had returned to Oklahoma, as the government demanded, or remained in Nebraska to die, his people would have ceased to exist, says Major Robinson, whose Great-Great-Grandmother Humpback Woman survived the march. “It’s truly amazing what they did,” he adds.

That’s why so many people’s hearts broke when, in 2000, descendants of those brave Northern Cheyennes discovered next to nothing at Fort Robinson commemorated their plight. Edna Seminole and Rose Eagle Feathers found only a simple sign—pockmarked with bullet holes—designating the spot. They declared their ancestors deserved better. That marked the beginning of the Northern Cheyenne Breakout Monument that now stands on a hill near Fort Robinson State Park.

Robinson, an architect who designed buildings around the world before returning to the Northern Cheyenne reservation in southeastern Montana in 1999, worked with a tribal committee to design the pipestone-clad obelisk, topped by a morning star, symbolizing the Cheyenne name for Dull Knife.

Calling the monument “pretty powerful,” Robinson says, “This is not just about remembering, but about healing for the next generation—not just for tribal people, but for non-tribal people as well. It’s amazing how many donations came from the people of Nebraska.”

The $150,000 raised for the monument included major contributions from Chief Dull Knife College, the Northern Cheyenne Tribe, Western Energy and St. Labre Indian School.

Robinson admits he was shocked when he learned about the breakout, history he had never heard while growing up. Now his children know the story. He and his wife have taken their two girls and son to Fort Robinson. “The kids question why it happened—why we were treated like that,” he says. “It makes them sad, but proud of being Cheyenne.”

Nearly 140 years have passed since the tragedy, he says, but now everyone can learn about the courage and determination of the Northern Cheyennes.

Arizona’s Journalist of the Year, Jana Bommersbach has won an Emmy and two Lifetime Achievement Awards. She also cowrote and appeared on the Emmy-winning Outrageous Arizona and has written two true crime books, a children’s book and the historical novel Cattle Kate.