Joseph Meek and Robert Newell knew the landscape of the West by 1840, since both had been working beaver streams throughout the Rockies and beyond for more than a dozen years. They would make their own history by taking the first wagons to Oregon late that fall,

Joseph Meek and Robert Newell knew the landscape of the West by 1840, since both had been working beaver streams throughout the Rockies and beyond for more than a dozen years. They would make their own history by taking the first wagons to Oregon late that fall,

using vehicles that had been discarded by other travelers to the Pacific Northwest.

Earlier that year Joel P. Walker, a man who had helped to pioneer the Santa Fe Trail, set off from Fort Osage for Oregon Country with his wife and five children and three missionaries and their wives. They traveled with an American Fur Company brigade across what would later become Kansas, Nebraska and Wyoming. The brigade, led by Andrew Drips, had sixty pack miles, a number of two-wheeled carts and some wagons.

When the group had crossed South Pass, the Walker family and missionaries Philo B. Littlejohn, Harvey Clark and Alvin T. Smith, guided by mountain man Robert Newell, continued west to Fort Hall, a trading post of the Hudson’s Bay Company. There they abandoned their wagons, continuing on to The Dalles by using mules to haul their goods. Ultimately they reached Vancouver, where HBC Factor Dr. John McLoughlin agreed to provide them with supplies for their first year of living in the region.

By taking his family to Oregon, Joel Walker earned distinction for helping to break ground for overland migration, and the first transcontinental trail.

Missionaries and Mountain Men

Four years earlier, in 1836, the missionary couples of Dr. Marcus and Narcissa Whitman, and Henry and Eliza Spalding had taken a similar journey with a trading brigade from Missouri to the fur trapper rendezvous. The missionaries continued to Fort Hall and ultimately rode horses to the missions they established in the Columbia Basin near Lapwai (Spalding) and Fort Walla Walla (Whitman).

This early travel by families over what was becoming the Oregon Trail had a common theme: families or missionary couples joined a fur trade brigade for the first half of the journey, using some carts to haul goods as far as Fort Hall, and beyond that point they relied on horses or pack mules to carry supplies.

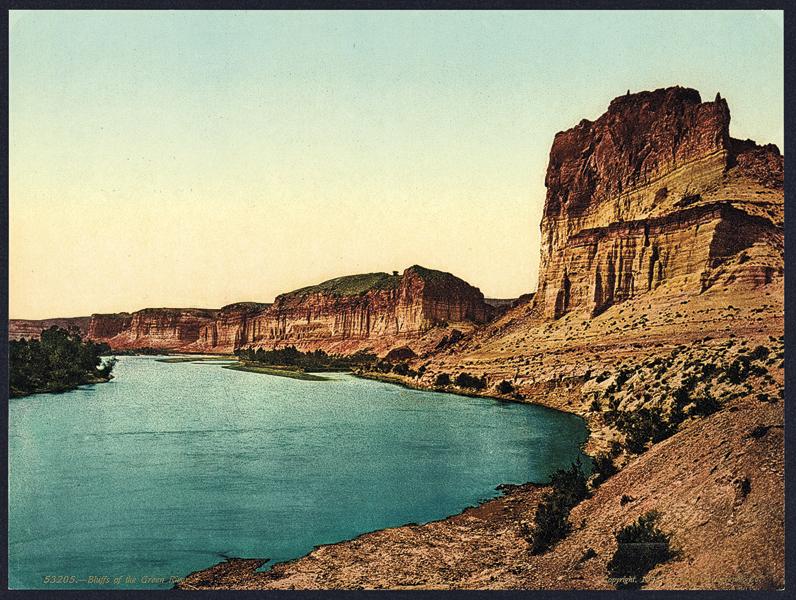

The 1840 rendezvous on the Upper Green River was the last of an era and trappers were recognizing that the West was beginning to change. They had seen the early families and missionaries pass through the country. Some, like Jim Bridger, began thinking of ways they could capitalize on future travel. Two years later Bridger would join Louis Vasquez in opening a trade post at a place he knew would be in the “path of the emigrants.”

A Virginian by birth, Joe Meek was 19 years old in 1829 when he signed on with William Sublette’s Rocky Mountain Fur Company. He spent the next eleven years trapping and trading throughout the Rocky Mountains. He had traveled to California in 1833 with Joseph Walker (Joel Walker’s brother), fought Blackfeet, battled grizzly bears, married three Indian women, but also recognized the coming end of the fur trap-per era.

Following the rendezvous in 1840, Meek and Newell, who had been born in Ohio in 1807, guided their families to Fort Hall, taking 17 days to make the journey. There they decided to continue on westward. Unlike the earlier travelers to Oregon Country, they took the wagons Newell had purchased from the Walker party and traveled along the Snake River, deep into Oregon Territory, which at that time started at the Continental Divide.

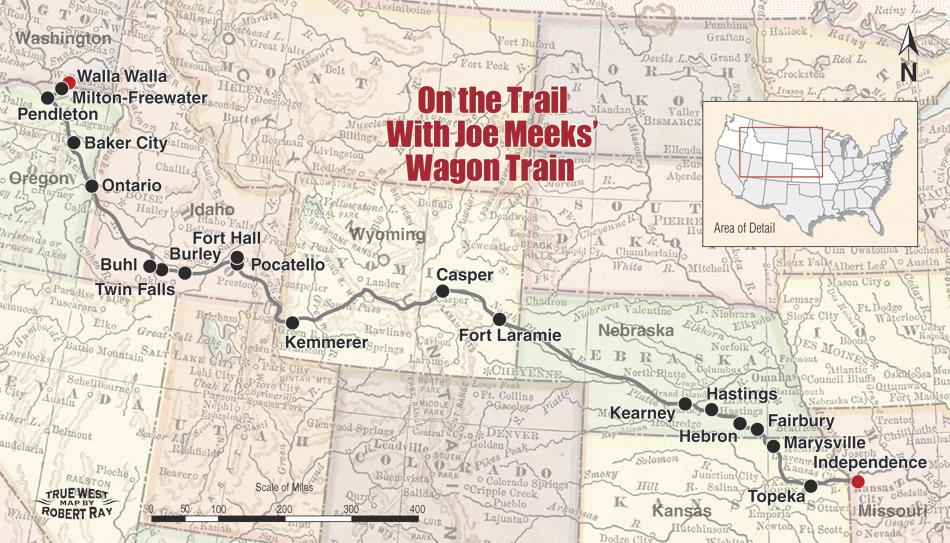

Independence, Missouri, to Fort Laramie, Wyoming

The mountain men did not begin their journey along the Missouri River in 1840, but to understand the trail they forged, that is where we will begin our trip since it is where nearly all Oregon-bound travelers over the next two decades started their journeys into the West. The National Frontier Trail Center in Independence, Missouri, provides a good overview of the trail to Oregon, and you will be able to follow the route west from this point by watching for the Oregon Trail auto tour route signs. To better guide you, pick up a copy of the auto tour route booklets prepared by the National Park Service. These guidebooks are free and include a variety of photographs, maps and some quotes from pioneers.

From Independence, travel west across Kansas to Fort Kearny, a pioneer-era post established in 1847 near Kearney, Nebraska. This site became extremely important for later pioneer travelers, as a location where they could rest and resupply. But our journey continues across Nebraska to Fort Laramie, which has roots reaching back to the fur trade era.

Initially called Fort John, the post served the American Fur Company as a place for early fur trappers to negotiate trades of furs for supplies. It also served as an important emigrant trading location. In 1847 it became an American military post, in part to protect travelers on the road leading to Oregon.

In 1840 there were no other permanent posts anywhere in what is now Wyoming (Fort Bridger began operations in 1842). The next supply and provisioning point was at Fort Hall, the fur post established by the Hudson’s Bay Company. Located in today’s eastern Idaho, Fort Hall was in Shoshone and Bannock country. While travelers had already crossed prairie, plains and the Continental Divide, from Fort Hall west, they still had a difficult journey to undertake before reaching the end of the trail.

On September 27, 1840, Newell and Meek along with their families, departed from Fort Hall. Newell recalled: “I concluded to hitch up and try the much-dreaded job of taking a wagon to Oregon…we put out with three wagons; Joseph L. Meek drove my wagon. In a few days, we began to realize the difficult task before us, and found that the continued crashing of sage under our wagons, which was in many places higher than the mules’ backs, was no joke. Seeing our animals begin to fail, we began to lighten up, finally threw away our wagon beds, and were quite sorry we had undertaken the job. All the consolation we had was that we broke the first sage on the road, and were too proud to eat anything but dried salmon skins after our provisions had become exhausted.”

Fort Hall, Idaho, to Walla-Walla, Washington

The road to Oregon from Fort Hall across Idaho goes to Twin Falls and then follows the Snake River. US 30 from Twin Falls through Burley and Buhl goes along the path the emigrants took, and offers views of the Thousand Springs before it follows the Snake River to Glenns Ferry, site of the important Three Island Crossing of the Snake. The 19th-century travelers left the Snake River at Farewell Bend, in present-day Oregon. But before you reach that point, make a stop in Ontario, Oregon, at the Four Rivers Cultural Center, which interprets the history of the emigrants and the American Indians who have long had connections to this region.

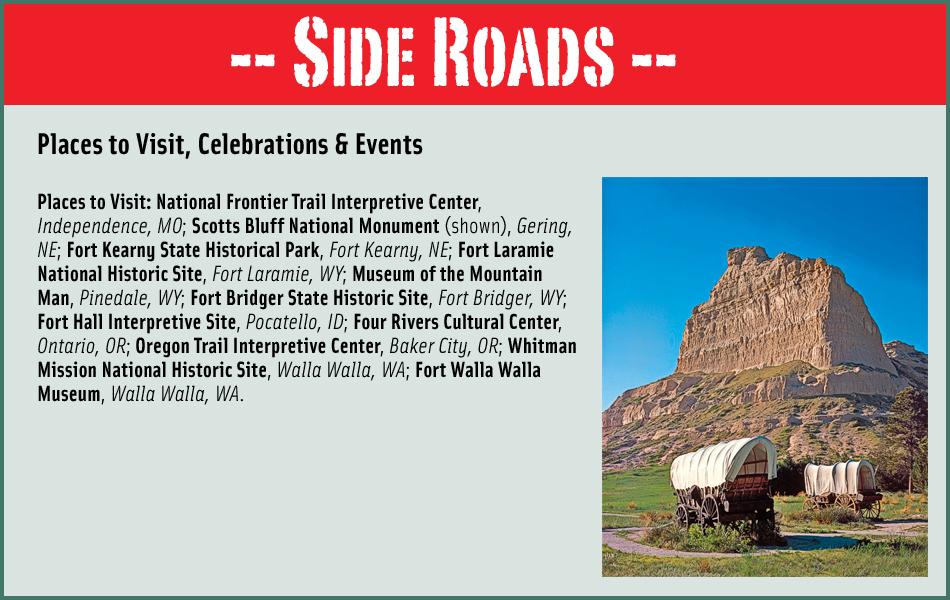

Thousands of emigrants would ultimately follow the route Joe Meek and Robert Newell took in 1840. The Oregon Trail Interpretive Center on Flagstaff Hill near Baker City, Oregon, not only provides information about the journey and the people who undertook it, but is also a site from where you can clearly see the trail ruts emigrant wagons left behind. For the best views of the trail remnants, try to time your visit in the early morning or late afternoon, when long shadows make the swales more prominent.

Meek drove his wagon through this country and on to the mission that had been established by the Whitmans. As Newell recalled, “In a rather rough and re-duced state, we arrived Dr. Whitman’s mission station, in the Walla Walla valley, where we were met by that hospitable man, and kindly made welcome, and feasted accordingly.”

After a day or two of rest and respite at the mission, Meek and Newell continued on to Fort Walla Walla. Newell wrote, “We were kindly received by Mr. P. C. Pambrun, chief trader of the Hudson’s Bay Company, and superintendent of that post.”

This small wagon train—which had successfully been brought from Missouri to Fort Hall by the missionaries, and then driven from Fort Hall to Fort Walla Walla by the intrepid fur trappers—was the first to cross the continent. Just as Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Spalding had proven in 1836, this train made it clear that the great overland migration could be completed by families carrying their household goods.

Trails Blazers Settle California and Oregon

In 1841 John Bidwell and John Bartleson organized a wagon train they intended to take to California, but upon reaching Fort Hall, they split the party and a number of travelers instead headed to Oregon. Just two years later the first large wagon train of emigrants traveled west with Jesse Applegate leading 1,000 people with 120 wagons from Missouri to Oregon.

Back in 1840, once Newell and Meek had reached Fort Walla Walla, they rested for a period and then took the river trail toward Western Oregon, ultimately arriving in the Willamette Valley in December. Newell and Meek would become important early leaders in organizing the provisional government for Oregon Territory.

Meek’s young daughter, Helen Mar Meek, was three years old when the family first reached the Whitman Mission. At age 10, in 1847 Helen was at the Whitman Mission under the care of Dr. Whitman as she suffered from measles. When Cayuse Indians attacked the Whiteman Mission on November 29, 1847, they killed many at the site including the Whitmans and Helen Meek. Following the attack at the Whitman Mission, Joe Meek organized a delegation from Oregon Country and went to Washington, D.C., to ask for protection and the designation of Oregon as a territory. He had some influence there in part because President James K. Polk’s wife was Meek’s cousin. Once the territory was established, Meek had a role in maintaining law and order.

Candy Moulton is the author of Wagon Wheels: A Contemporary Journey on the Oregon Trail, co-written with Ben Kern and published by High Plains Press, and the producer/writer of the Spur Award-winning film In Pursuit of a Dream about the Oregon Trail. She is a lifetime member of the Oregon-California Trails Association.

Photo Gallery

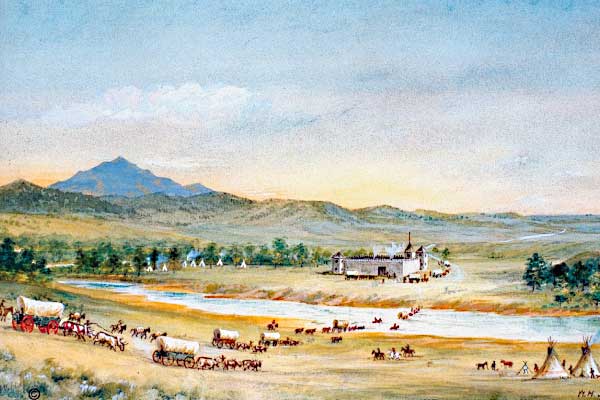

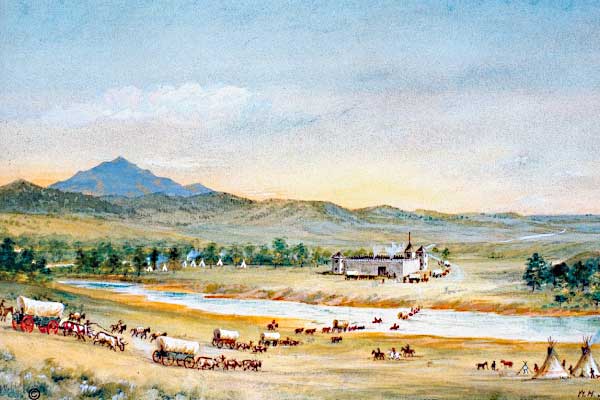

When Robert Newell and Joseph Meek set out for Oregon Country in 1841, they took wagons that had been abandoned at Fort Hall and drove them to Fort Walla Walla.

– Courtesy National Archives, photo no. 57-HS-119 –

– Courtesy Peg Owens, Idaho Tourism –

– By William Henry Jackson, Courtesy NPS –

– True West Archives –

– Courtesy Idaho Tourism –

– Courtesy BLM.gov –

– By William Henry Jackson/Library of Congress Courtesy –

– Courtesy Peg Owens, Idaho Tourism –

– Courtesy NPS.gov –