Every first-time movie director thinks he is making the next Citizen Kane. Few are correct. But director and star Kevin Costner did something his first time at bat that no other freshman filmmaker ever has: his film won seven Oscars.

Every first-time movie director thinks he is making the next Citizen Kane. Few are correct. But director and star Kevin Costner did something his first time at bat that no other freshman filmmaker ever has: his film won seven Oscars.

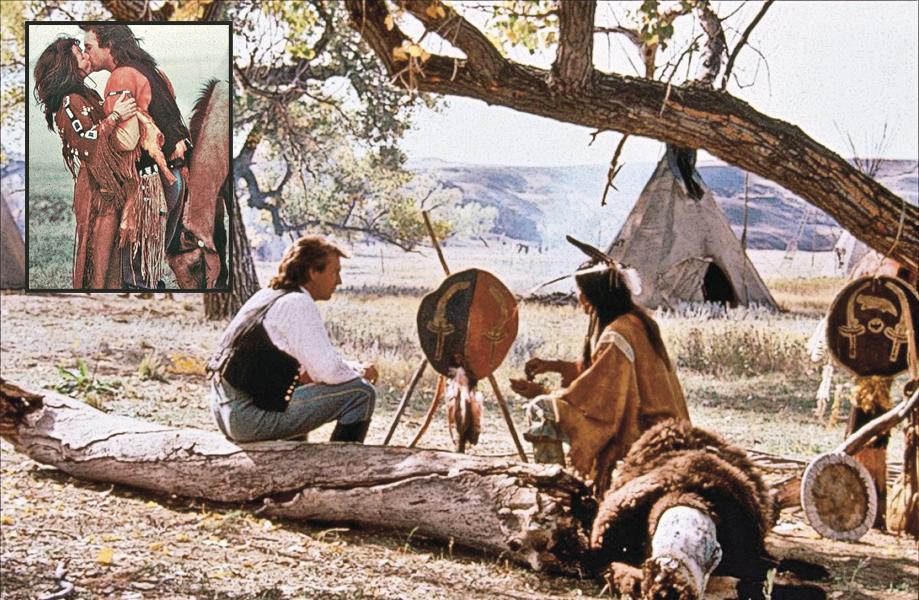

Dances With Wolves, released 25 years ago, garnered Costner both Best Picture and Best Director awards. The film also won Best Screenplay, Score, Editing, Cinematography and Sound. Aside from these well-deserved awards, Costner did something else remarkable: he made an epic Western that was both a critical and popular success, taking in more than $184 million.

The excesses and financial disaster of 1980’s Heaven’s Gate had nearly killed the Western. Costner proved the genre still had plenty of life and artistic value, and that huge audiences, male and female, would come out to see a good one. Arguably, without the success of Dances With Wolves, we might not have gotten 1992’s Unforgiven, 1993’s Tombstone or 1994’s Wyatt Earp.

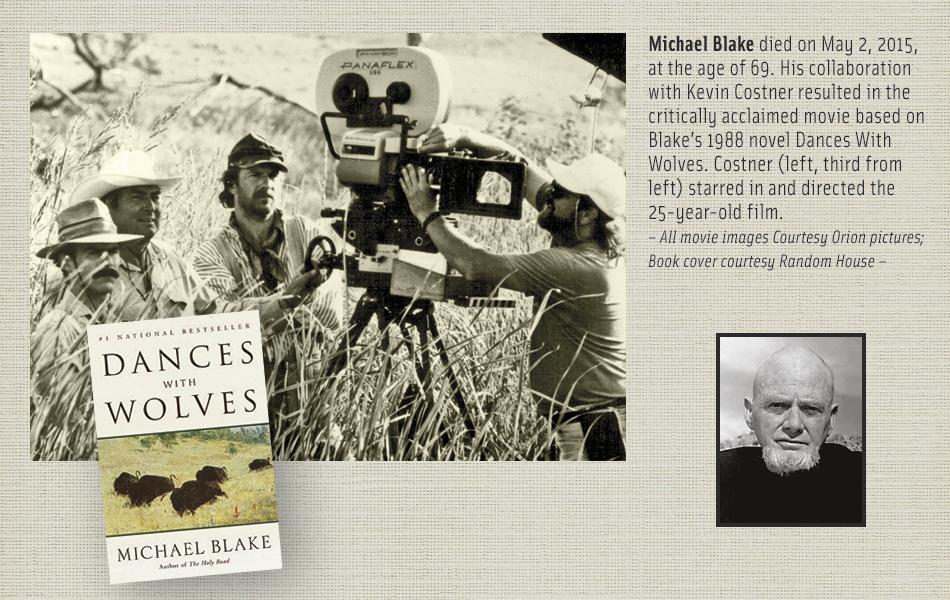

Costner’s equal partner in this great success was Michael Blake. They met on the set of 1983’s Stacy’s Knights, written by Blake and starring Costner. The writer told the actor a story he had been toying with concerning Lt. John Dunbar, an inadvertent Civil War hero assigned by a madman to the farthest fort on the American West frontier. There, he learns about himself through hardship and brutal danger, and learns about the American Indians who have been dismissed as “thieves and beggars.” His life is forever changed.

Blake, who passed away this May, at age 69, not only left Dances With Wolves as his legacy, but also other Western stories to come.

We, the audience, have our own special memories of the film: the buffalo hunt, the opening battle, the beautiful South Dakota vistas, Dunbar’s romance with Stands With A Fist.

Those lucky enough to have worked on the film will never forget the experience. Bill Markley authored Dakota Epic, his day-to-day account of being a re-enactor on Dances With Wolves. He later shouldered a musket in 1991’s Son of the Morning Star, 1992’s Far and Away and 1993’s Gettysburg.

“It really was kind of a family; Kevin and Michael and [producer] Jim Wilson were close friends, and that esprit de corps really rubbed off on everybody. I didn’t experience that comradeship, that friendliness, on any other movie sets,” Markley says. “There was one where, if you tried to talk to the actors you’d be fired immediately. To have the opposite kind of experience first spoils you for everyone else.

“Michael Blake was a really nice guy. He’d stand with three sweaty, grubby

guys to have his picture taken. Blake said he had Kevin in mind when he wrote the book. He was going through a divorce and living out of his car. He’d go over to the Costners’s house to take showers when he was writing it.”

Daniel Ostroff, who produced 2003’s The Missing, was Blake’s agent during Dances With Wolves and has been his producing partner in recent years. “Michael was there for about half of the shooting, when he had to come home,” Ostroff says. “Kevin had invested his own salary in the movie; he wasn’t getting paid. It was costing $1,000 a week to keep Michael there, and they just couldn’t afford it. Kevin was committed to shooting every single word [of the script]. A few months after principal photography, we watched Kevin’s first cut. We were blown away—Michael’s vision was all there on-screen, and that’s 100 percent owing to Kevin.”

One of the most recognized of American Indian actors, Wes Studi, gained lasting fame as Magua in 1992’s The Last of the Mohicans, starred as Geronimo in 1993’s Geronimo and is currently in the Sundance series The Red Road. Of his chilling role as Toughest Pawnee in Dances With Wolves, Studi reflects, “After 25 years, I readily admit it was the firecracker that got my career started.

“There’d been a feeling, certainly amongst the Indian cast, that this was going to be a breakthrough film. There were a lot of aspects that hadn’t been done in a good long while. Like the languages, and that we got inside the head of Graham Greene’s character, and Wind In His Hair, and got to see a lot of real life happening in the Lakota camps. There was a feeling that this was going to be a successful film, but certainly not to the extent that it came to be successful.”

Studi’s most vivid memory of the filming? “Maybe my death scene,” he says. “When they all surround me and fire away, and I roll off the back of the horse—into very cold water. I kid my Lakota friends about how it took that many Sioux to kill one Pawnee—and they all had guns.”

Happily, the saga of Lt. Dunbar is not at an end. Ostroff has licensed Dances With Wolves as a Broadway musical. He is also producing Blake’s sequel novel, The Holy Road, for either the large or small screen. Additionally, Blake’s script for Winnetou, based on German writer Karl May’s Western novels, will be produced by Constantin Film. The Western genre hasn’t seen the end of Blake just yet.

Henry C. Parke is a screenwriter based in Los Angeles, California, who blogs about Western movies, TV, radio and print news: HenrysWesternRoundup.Blogspot.com