— True West Archives —

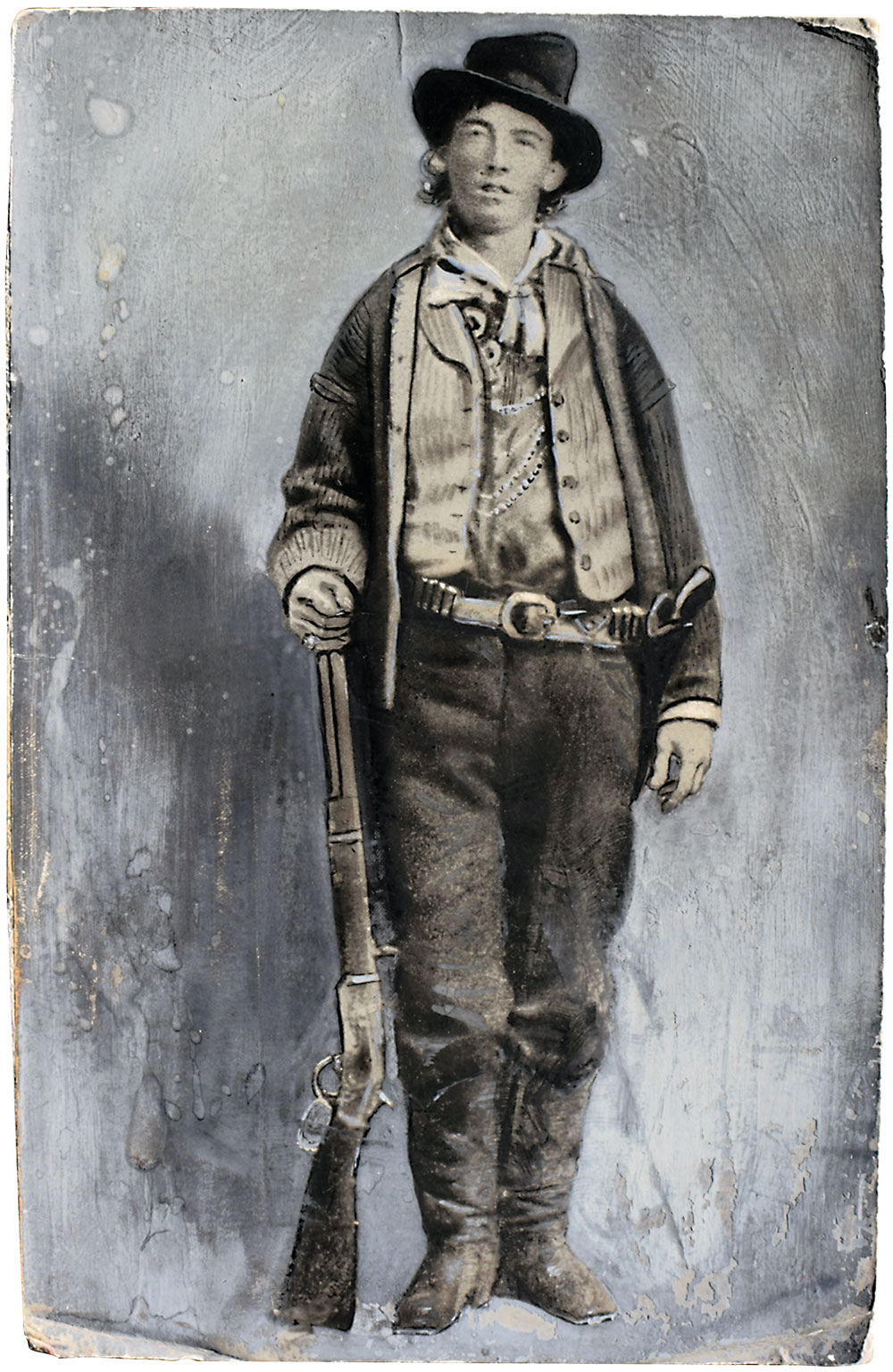

“He is, in all, quite a handsome looking fellow.” That was the opinion of a newspaperman fortunate enough to obtain an interview with the notorious outlaw Billy the Kid inside a Las Vegas, New Mexico Territory, jail cell in late December 1880. The Kid, as described by the curious reporter, was five feet eight or nine inches tall, slightly built, and looked like a schoolboy. Instead of whiskers, the 21-year-old outlaw still had “silky fuzz” on his upper lip. And his eyes were a clear blue “with a roguish snap about them.”

The only thing that took away from the young man’s good looks were those now-famous two front teeth. They stuck out, the reporter wrote, “like squirrel’s teeth.” Of course, as one fellow who’d known Billy commented, you wouldn’t have noticed those buck teeth if the Kid wasn’t always laughing and smiling.

— Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin Collection —

Quite a crowd of Las Vegas citizens also got a glimpse at what the newspapers had portrayed as the terror of the Southwest. Billy was glad. He told the reporter that “perhaps some of them will think me half man now; everyone seems to think I was some kind of animal.”

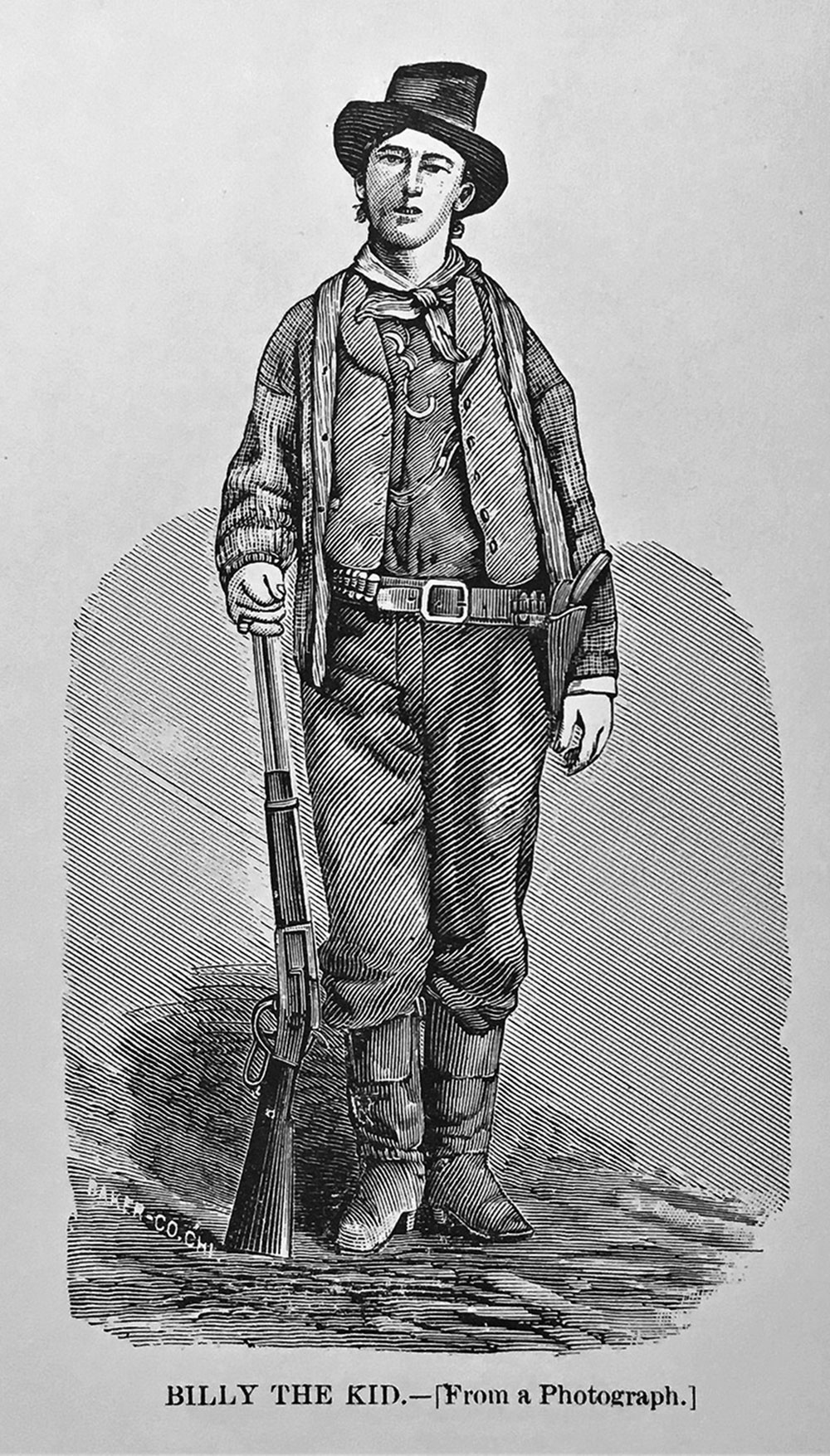

It wasn’t only New Mexicans who wanted a good look at the Kid. His killings and thievery had made national headlines, especially within the last few months. And after Sheriff Pat Garrett tracked down and captured the Kid and three cohorts near Fort Sumner, there was an immediate demand for some kind of image of the outlaw, particularly from a Boston weekly called the Illustrated Police News, which specialized in sensational stories of assorted crimes and criminals. The Police News didn’t have to wait long.

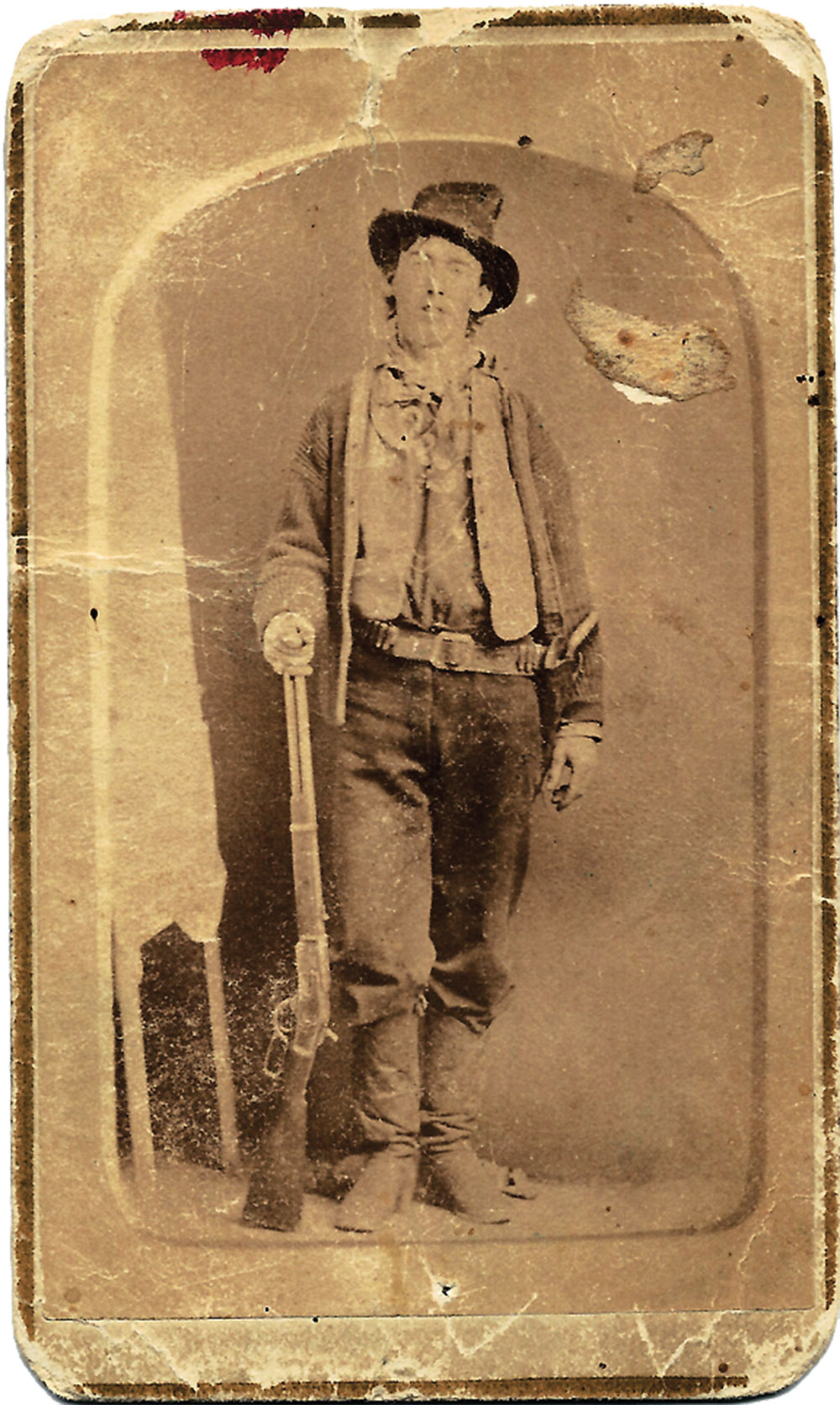

Sometime earlier that year, a traveling photographer had set up shop at Fort Sumner. The photographer’s name is unknown, but he was a “tintypist” with a multi-lens box camera that, in a single exposure, created four identical images on one japanned metal plate. After developing and fixing the images on the thin plate, the photographer simply snipped the four identical portraits apart. Price: 25 cents for all four. It was definitely a bargain, but there was no negative involved in the process, so those four images were all one walked away with.

One part-time Fort Sumner resident who was happy to spend two bits for some tintype likenesses was William H. Bonney, a.k.a. Henry McCarty, Henry Antrim, Kid Antrim and Billy the Kid. In a matter of minutes, a head-cocked Bonney, in rumpled frontier garb with Winchester rifle and Colt six-gun, was preserved for posterity. Perhaps if the tintypist had known that the photograph he made that day would become one of the most iconic images in American history, and the only undisputed authentic photograph of the Kid in existence, he might have made sure his name was somewhere preserved with the image.

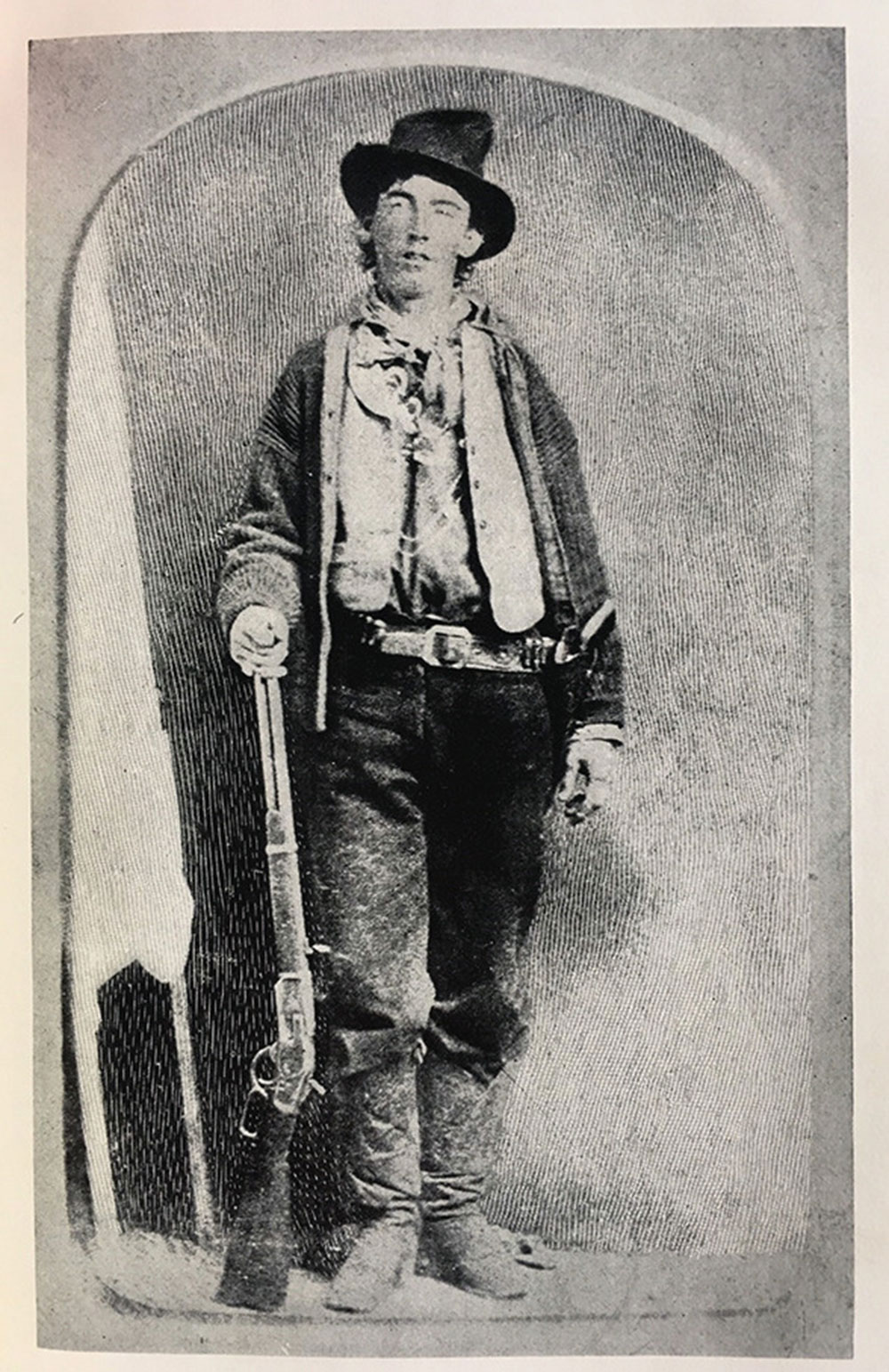

The Illustrated Police News presumably became the first to secure one of these four tintypes and published an engraving based on it. The illustration appeared in its January 8, 1881, issue, just 12 days after Billy was locked up in the Las Vegas jail. The Police News credited Las Vegas Chief of Police E. Roberts for the image, which he had ob-

tained “from Lincoln County, N. M., Bonney’s old home.”

The Las Vegas Daily Gazette heavily criticized the Police News’ illustration of Bonney: “The likeness of ‘the Kid’ would do service for all men in general, and certainly has no resemblance to the daring young fellow.” When the Illustrated Police News published the illustration again the following March, the Gazette’s competitor, the Las Vegas Daily Optic, also took a shot at the portrait, calling it “miserably concocted.”

Surprisingly, it seems that no other periodical or newspaper copied this particular engraving. What happened to the tintype sent to the Police News and whether or not it was returned to Chief Roberts is unknown.

And what happened to the other three tintypes from Billy’s Fort Sumner sitting?

Pat Garrett obtained one, either from Billy himself after capturing the outlaw gang in December 1880, or after shooting the Kid dead at Fort Sumner on July 14, 1881. “It is said that there is only one photograph of Billy the Kid extant, and Pat Garrett has that,” reported the Santa Fe Daily New Mexican in its edition of October 1, 1881. It jokingly added that, “Most people in this section have seen as much of the Kid as they want to, and will be able to get along without a picture.”

— All Images Courtesy the Mark Lee Gardner Collection Unless Otherwise Noted —

That very same tintype was undoubtedly the source for the engraving that appeared as a frontispiece in Garrett’s biography of the Kid, the seminal The Authentic Life of Billy the Kid, published in Santa Fe in 1882.

Pat Garrett retained possession of this tintype for the rest of his life. In 1902, he told a newspaper reporter: “I’ve got a tintype of Billy at home, the only one in existence, I believe, and as I was on the way to the train I left it at a photographer’s to be enlarged for Gen. Lew Wallace, who wants to write an article about him.” Wallace, the former

New Mexico Territorial governor famed (or notorious) for once offering Billy a pardon, never wrote that article. The whereabouts of the photographic enlargement Garrett had made of his tintype is unknown.

— Courtesy Newberry Library —

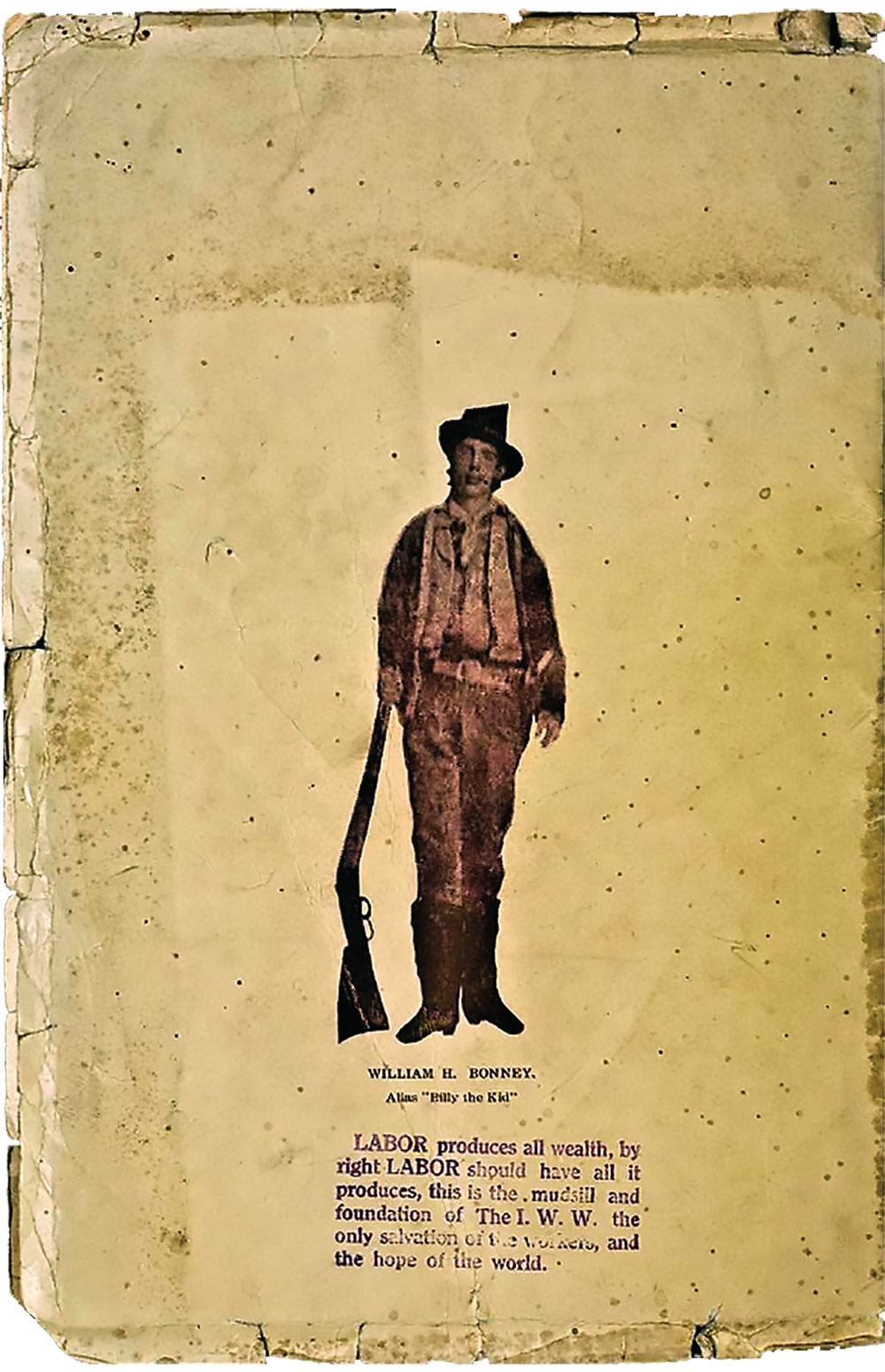

Pat Garrett’s Billy tintype appears in the historical record for the last time in 1908,

just a few short weeks following the lawman’s February 29 murder near Las Cruces, New Mexico. Garrett admirer John Milton Scanland hastily put together a short biography of the sheriff titled The Life of Pat F. Garrett and the Taming of the Border Outlaw. Featured on the back cover of this slim booklet is a photograph of Billy the Kid.

Under the bold headline “ONLY PHOTOGRAPH OF BORDER OUTLAW,” the Albuquerque Morning Journal reported on Scanland’s visit to Albuquerque to promote his book. The proud author related how the photograph on the back was made from an original tintype loaned to him by one of Garrett’s daughters (probably Pauline). The tintype, Scanland claimed, was “believed to be the only picture of the desperado in existence.”

Unfortunately, the photographic reproduction printed on Scanland’s book was heavily cropped and doctored—the Kid’s Winchester has been oddly flipped around and moved out at an angle away from his body. Nevertheless, it’s obvious that the photo reproduced by Scanland was indeed based on the original tintype owned by Garrett.

Garrett’s Billy tintype disappears after 1908 and has not surfaced since. It’s worth noting, however, that Garrett and others at the time never mentioned any additional photographs picturing the Kid. A tintype of five rough-looking men purchased at a North Carolina flea market in 2011 is claimed by its owner to include both the Kid and Garrett. But if Garrett indeed sat with the Kid for a photograph, why would he—and his family—consistently refer to the Billy the Kid tintype in Garrett’s possession as the only one in existence? It seems highly unlikely that Garrett wouldn’t recall such a momentous photo shoot for which he posed with New Mexico Territory’s most wanted man.

The history of another of Billy’s four tintypes is easily traced. It’s the tintype the outlaw gave to pal Dan Dedrick, and it’s this image that most people around the world are familiar with today. Except for a short time the tintype was displayed at New Mexico’s Lincoln Historic Site in the 1980s, it remained in possession of Dedrick descendants until it was sold at auction in Denver, Colorado, in 2011 for $2.3 million with buyer’s premium. The happy winning bidder was billionaire and Old West enthusiast William I. “Bill” Koch. It remains the highest price paid for a 19th-century photograph, and the immediate result was a crazed hunt for any previously unknown photographs of the charismatic outlaw, as well as a booming business for photo “authenticators.”

The fate of the last of the four Billy tintypes comes courtesy of Paulita Maxwell Jaramillo, generally acknowledged then and now as Billy’s Fort Sumner sweetheart. She told author Walter Noble Burns in 1923 that the Kid had given one of his tintypes to family servant Deluvina Maxwell after Garrett’s posse had stopped at Fort Sumner with their prisoners in December of 1880. “He could not have given Deluvina nothing she would have prized more,” Paulita said.

Paulita’s mother kept Deluvina’s Billy tintype in her cedar chest for several years, until, for whatever reason, she gave the photo to Fort Sumner saloonkeeper John Legg. Legg was killed in his saloon in an argument over a poker game in 1899, and the tintype passed into the hands of Legg’s executor, Fort Sumner old-timer Charlie Foor. When Foor’s home later burned, so did Billy. But, Paulita added, “many copies of it had been made.”

One of the “copies” Paulita may have been referring to surfaced in 2013, a carte de visite photograph (CDV) that is clearly a copy of one of the four original tintypes. A CDV is a small photograph on albumen paper that is mounted on card stock. The process to make a CDV requires a glass-plate negative, from which multiple copies can then be made. The Billy CDV’s mount style, with its thick gold border, fits perfectly into the 1881-82 period. In fact, a Leavenworth, Kansas, newspaper reported in September 1881, that it had obtained a “genuine picture of Billy the Kid” with the intention of having copies made. Despite copyright issues, making copies of copies of photographs was quite common in the 19th century, especially when there was a buck to be made.

The Billy CDV, and we don’t know if it was the specific CDV discovered in 2013 or another print, would be used as an illustration in two publications appearing in 1907. These were Emerson Hough’s The Story of the Outlaw and the two-volume set titled History of New Mexico: Its Resources and People.

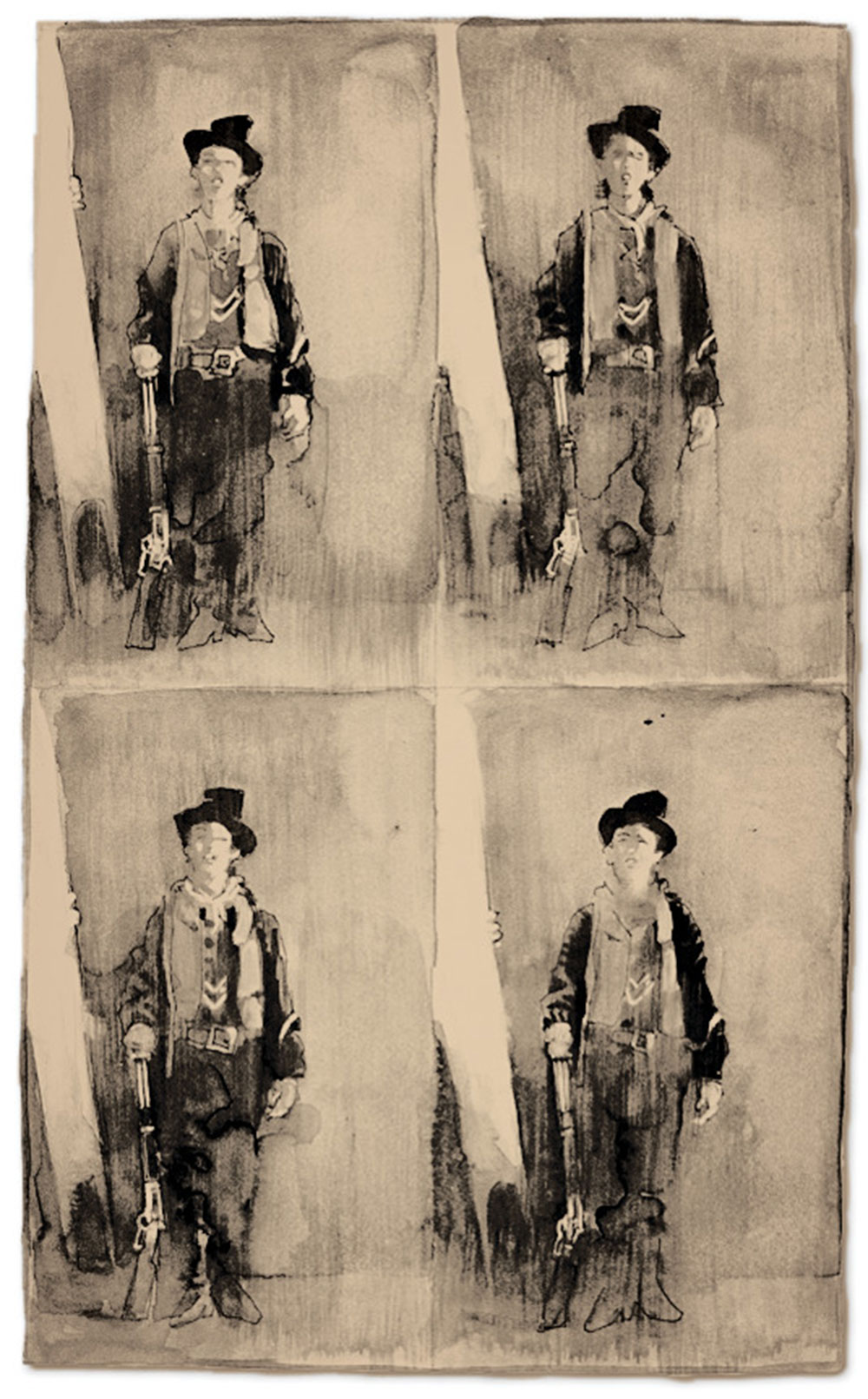

Once the Billy CDV was published, other authors made use of that version of the Kid for their own books and articles, until the Dedrick tintype surfaced decades later. Walter Noble Burns, whose hugely popular The Saga of Billy the Kid (1926) made the young outlaw immortal, commissioned an illustration of Billy based on either an original Billy CDV or, more probably, the CDV version as published in 1907. Burns’s illustration is a heavily touched-up halftone that is one of the more attractive interpretations of the original tintype. However, Burns’s publisher, Doubleday, Page & Company, opted not to use any of the images Burns submitted for his book, explaining that they preferred to let his readers use their imaginations.

Not to worry, Burns finally got to use his Billy illustration for the London edition of his book, published in 1930 by Geoffrey Bles under the simple yet direct title Billy the Kid. The image appeared prominently as that book’s frontispiece.

While Paulita Maxwell Jaramillo didn’t live to see Burns’s Billy frontispiece, that was just as well. She didn’t care whether Billy’s iconic photo was an original tintype, an engraving from a tintype, a CDV copy, or a copy of a copy of a copy. She was of a mind with the Las Vegas press: the portrait was awful.

“I never liked the picture,” Paulita told Burns. “I don’t think it does Billy justice. It makes him look rough and uncouth. The expression of his face was really boyish and very pleasant. He may have worn such clothes out on the range, but in Fort Sumner he was careful of his personal appearance and dressed neatly and in good taste.”

Such were the recollections of a 59-year-old woman who once knew Billy the Kid as much more than “half man.”

Mark Lee Gardner is the author of To Hell on a Fast Horse: The Untold Story of Billy the Kid and Pat Garrett (New York: William Morrow, 2011). He is currently writing a dual biography of Lakota leaders Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull.