– Courtesy NPS.gov. –

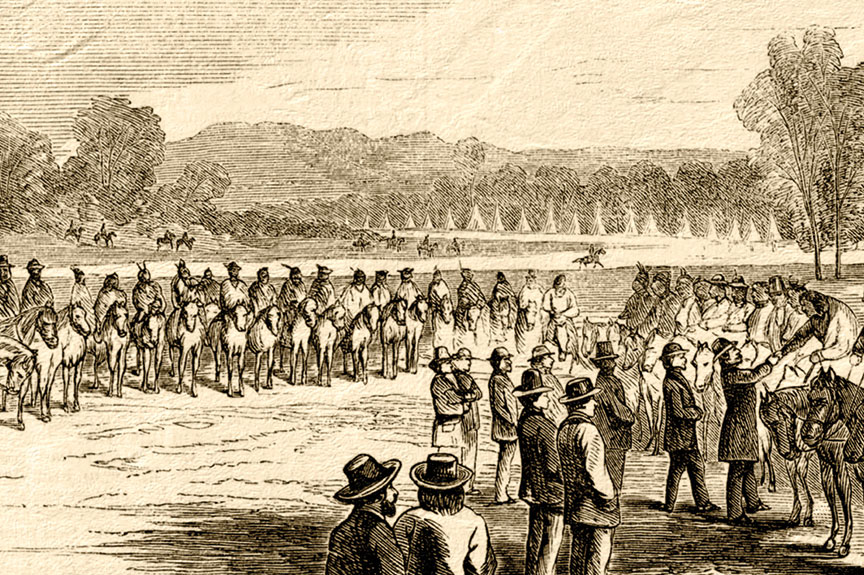

Hoping to end the 1867 plains war, over 5,000 Indians camped on the Medicine Lodge peace council grounds in Kansas on October 14, 1867, but only Black Kettle’s band of Tsistsistas (Cheyennes) were present. The rest of the tribe had assembled on the Cimarron River in Indian Territory where Keeper of the Sacred Arrows Stone Forehead would renew them. Three days later Black Kettle attended an impromptu meeting with the commissioners. His attitude wasn’t the best. “We were once friends with the whites,” he said, “but you nudged us out of the way by your intrigues.” He wanted them to stop pushing each other. “Why don’t you talk and go straight, and let all be well?”

Later that day Tsistsista Dog Men (“Dog Soldiers” is a white man term) chiefs Tall Bull and Gray Head visited the council grounds. Before leaving Tall Bull confronted Black Kettle in his camp. He wanted to know why he wasn’t on the Cimarron River to participate in the renewal of the arrows. He told Black Kettle to travel to the Cimarron and tell the Called Out People what good another treaty with the vi´ho´ i—the white man—would bring. When Black Kettle refused, Tall Bull threatened to kill his horse herd. He also warned him not to speak. When the negotiations officially began on October 19, Black Kettle remained silent.

Three days later Dog Men returned to the council grounds in a downpour. They woke Black Kettle and forced him to ride to the peace commissioners’ camp. While they waited for the white men to dress, Black Kettle became livid when he argued with Little Robe. No interpreters were present, but an unnamed reporter viewed it, and later wrote: “[B]eing a peacemaker among the Cheyennes in 1867 was a dangerous occupation.”

– Courtesy True West Archives. –

– Courtesy Library of Congress. –

– Courtesy Library of Congress. –

– Courtesy Library of Congress. –

Senator John Henderson appeared and demanded that the Cheyennes attend council. Tempers flared, but Black Kettle stepped between the Dog Men and Henderson and ended the confrontation. Before departing, the Dog Men forced Black Kettle to ride to the Cimarron with them. The chief’s abduction upset the peace commissioners and reporters; most feared a Cheyenne attack.

The Kiowas and Comanches signed their treaty on October 21.

Finally, on October 27, Tsistsistas and Dog Men burst from the trees and rode across the creek as they shouted and fired their weapons. Black Kettle rode near the head of the charge. He was disheveled, but alive. It wasn’t an attack—the Cheyennes were ready to hear the vi´ho´ i’s words. The Cheyenne and Arapaho council began the next day, but again Black Kettle was advised to remain silent.

Only Dog Man chief Buffalo Chief spoke:

“We do not claim this country south of the Arkansas, but that country between the Arkansas and the Platte is ours.… You give us presents and then take our land; that produces war.”

The commissioners ignored Buffalo Chief. There was total silence. The Tsistsista leaders realized that the vi´ho´ i were done talking and began to walk away. Interpreter John Smith saved the day by getting them to listen to Henderson. He told them that they could roam “throughout the unsettled portions of…the country they claim as originally theirs, which lies between the Arkansas and Platte Rivers” to hunt buffalo. Henderson didn’t lie, but the treaty was never read to the Indians, and the U.S. government ignored his promise. Instead, the treaty would proclaim that the Cheyennes retained their right to hunt buffalo on their former land south of the Arkansas.

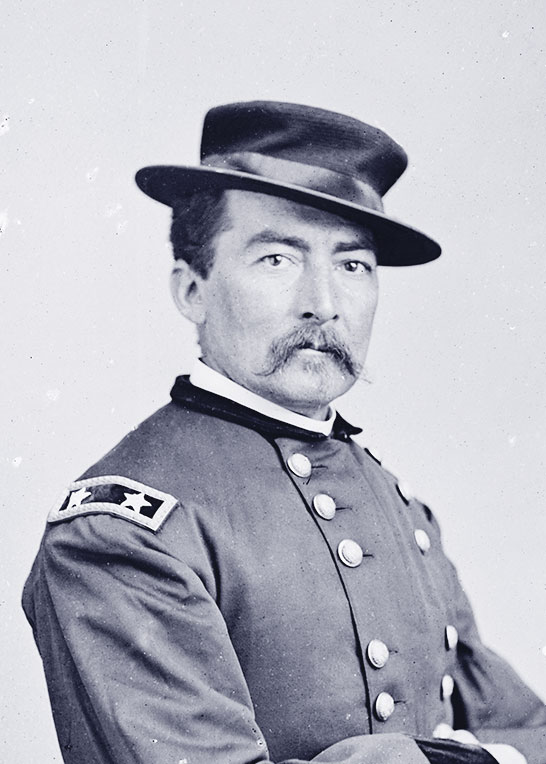

The winter of 1867–68 had been harsh, but the spring would be worse. In March, when Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan, who commanded the Division of the Missouri, blocked the issuing of weapons with the annuity distribution, Black Kettle and other chiefs didn’t hide their anger. It happened again in April, but Black Kettle didn’t complain as the Tsistsistas were in “a state of starvation.” During the May distribution, Black Kettle and Stone Forehead complained to Agent Ned Wynkoop about not receiving the promised weapons but accepted the supplies. Not so at the July 20 distribution, for as soon as Black Kettle and the other chiefs saw they would not receive weapons, they stopped the process. “[Our] white brothers [are] pulling away from [us] the hand they had given to [us] at Medicine Lodge Creek,” an angry Black Kettle said. He refused the shipment, while making it clear he “would wait with patience for the Great Father to” deliver the promised “arms and ammunition.”

Realizing the urgency, Wynkoop petitioned to have the arms released, and received permission providing that “no evil will result from such [a] delivery.” On August 9, Black Kettle and other chiefs camped near Wynkoop’s Fort Larned agency and agreed not to use the weapons on whites. The agent distributed the previously refused supplies and the guns. Black Kettle and the others were thrilled.

That same day, Lt. Gen. William T. Sherman created a military district for the Cheyennes, Arapahos, Comanches and Kiowas in Indian Territory that Lt. Col. William Hazen would command.

– True West Archives. –

But on August 10 an intended Cheyenne-led raid on the Pawnees in Nebraska that began on August 2 morphed into days of rape, destruction and death to white homesteaders on the Saline and Solomon rivers in Kansas. When Black Kettle, who was still camped near Fort Larned, heard what happened, he yanked his hair and ripped his clothing. Seeing the chief’s distress, Wynkoop told him if he “move[d] to Fort Larned he would take care of him.” Black Kettle refused the offer. (In mid-November 1864 the military had promised the Tsistsistas protection if they moved to Sand Creek, but that resulted in a massacre of the People on the 29th.) Although he intended to move onto the buffalo’s migratory path, Black Kettle decided to get his band as far away from the white man as possible and moved south with his followers into Indian Territory—his destination was the Washita River.

The chief’s gut reaction to the future was on target. On September 17, Lieutenant General Sherman declared war on the Cheyennes. There would be no more excuses, no more treaties, for this war would end the Cheyennes’ freedom on the central and southern plains.

Moons passed. Black Kettle learned that vi´ho´ i soldiers hunted the People south of the Arkansas. He also heard of a white peace chief at Fort Cobb, 119 miles east of his Washita village. Braving a bitter winter storm, he and others rode to meet Col. William Hazen.

– True West Archives. –

On November 20, Black Kettle said to Hazen: “I have always done my best to keep my young men quiet, but some will not listen, and since the fighting began I have not been able to keep them all at home.” But this was nothing new, and had been said to the white man time and again. Contrary to false statements, Black Kettle didn’t attempt to ransom captives for peace, for he had none.

Hazen sounded sincere, but he wasn’t open to Black Kettle moving to the “safe zone” that he commanded for Indians supposedly not involved in the current war. Two days later Hazen reported to Sherman: “To have made peace with [Black Kettle] would have brought to my camp most of those now on the warpath south of the Arkansas.”

Black Kettle wasn’t on the warpath. Nothing had changed—absolutely nothing—for Black Kettle was considered the chief of all the Cheyennes and this made him the foremost war leader.

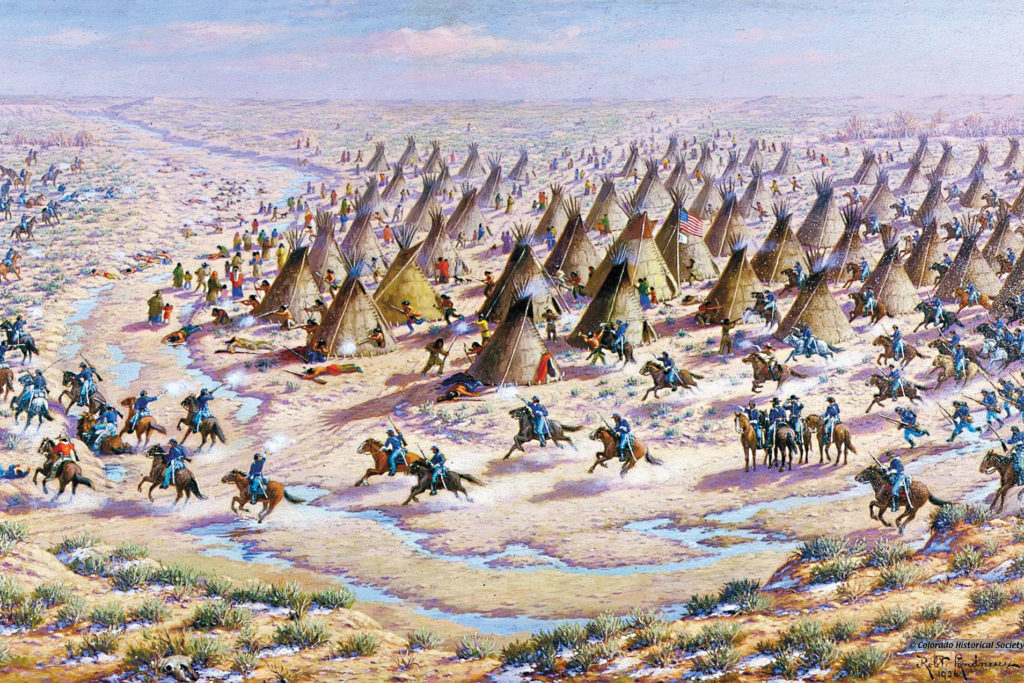

– Detail of Steven Lang’s “Battle of the Washita” Painting Courtesy Washita Battlefield NHS, NPS.gov. –

The evening of the 26th was freezing. Nevertheless, Black Kettle met in council with chiefs in his village. They undoubtedly discussed what they should do.

It didn’t matter…

At dawn, vi´ho´ i soldiers yelled as they charged into the village and fired their weapons. Women and children screamed in fright. The hell of Sand Creek—four years previous—had again become reality. Black Kettle mounted a horse tethered to his lodge, pulled his wife, Medicine Woman Later, up behind him and attempted to escape across the Washita. A minute later, maybe two, soldiers’ bullets ended their lives.

Lieutenant Colonel Custer and the 7th U.S. Cavalry had attacked the village without knowing its occupants. He would report that he killed 101 warriors, including Black Kettle, as well as some women and children. But, Custer’s death count is questionable—and will forever be so—for two mixed-blood Arapahos (Jack Fitzpatrick and John Poisal Jr.) who served under him, disagreed. They claimed that Custer “exaggerated; that there was not over 20 bucks killed; the rest, about 40, were women and children.”

Former Agent Wynkoop received Fitzpatrick and Poisal Jr.’s statement. When invited to speak at the Cooper Institute in New York City in December 1868, he had this to say about Black Kettle: “The whole force of his nature was concentrated in the one idea of how best to act for the good of his race.” Regardless of how the Called Out People viewed him, from the time that he became a chief in 1855 until his death, Black Kettle worked to prevent or end war between the races.