Illustrations by Bob Boze Bell.

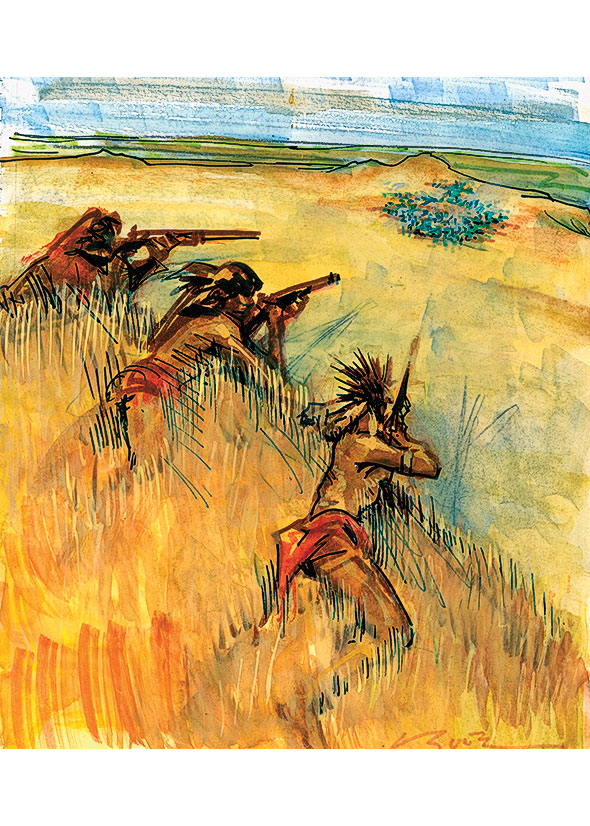

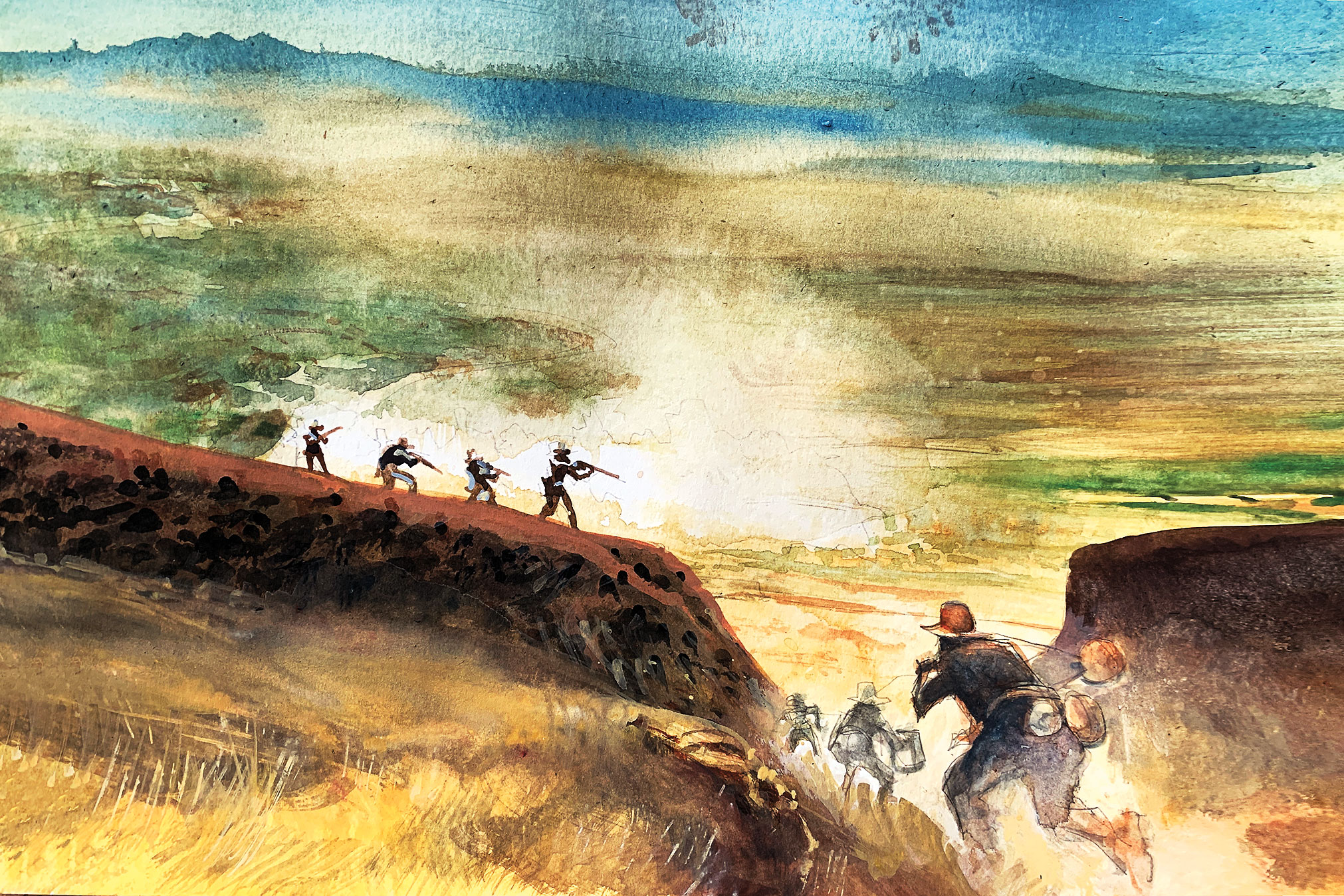

Raining Bullets

Private Charlie Windolph of H Company hunkers down as a hail of arcing bullets rains in on Reno’s command. Private Julien Jones is hit in the heart and dies instantly while Windolph has his rifle butt stock split in half by a bullet.

June 26, 1876

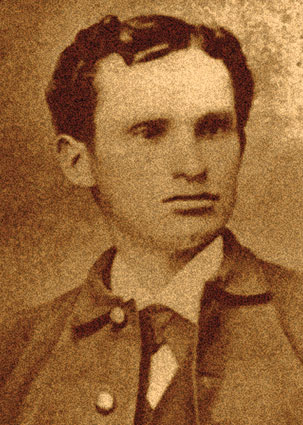

Riding with Major Benteen, Private Charlie Windolph finds himself surrounded at a spot that will become known as Reno Hill. Here is Windolph’s account of what happened the following morning: “Two shots sounded from the hilltop behind us. Soon there was firing all around. It had rained a little during the night and some of us had taken our overcoats from the cantles of our McClelland [sic] saddles and put them on. It was cold here on this bleak hilltop, too, and those old Army blue coats felt good.

“My buddy, a young trooper named Jones, who hailed from Milwaukee, was lying alongside me. Together, we had scooped out a wide shallow trench and piled up the dirt to make a little breastwork in front of us. It was plumb light now and sharpshooters on the knob of a hill south of us and maybe a thousand yards away, were taking potshots at us.

“Jones said something about taking off his overcoat, and he started to roll on his side so that he could get his arms and shoulders out, without exposing himself to fire. Suddenly I heard him cry out. He had been shot straight through the heart.

“The lead kept spitting around where I lay. Up on the hilltop I could see a figure firing at me from a prone position. Looked like he was resting his long-range rifle on a bleached buffalo head. I tried my best to reach him with my Springfield carbine but it simply wouldn’t carry that far.

“A few minutes after Jones was killed, a bullet ricocheted from the hard ground and tore into my clothing. About this time the surgeon came up and took a look at Jones. He asked me if I wasn’t wounded. I said no, that I was all right ‘Put your hand inside your shirt,’ he ordered. I did, and when I pulled it out it was bloody. The ricocheted bullet had given me a slight flesh wound. The surgeon wanted to bind it up, but I told him there were plenty of badly wounded men to take care of.

“A minute or two later another bullet from the hilltop tore into the hickory butt of my rifle, splitting it squarely in two. I was pretty mad because my Army carbine wouldn’t let me return the compliment. Somehow I always figured that the sharpshooter who had killed Jones, hit me and split my rifle butt, must have been either a renegade white man, or

a squaw man of some kind or another.He could shoot too well to have been a full-blooded Indian.”

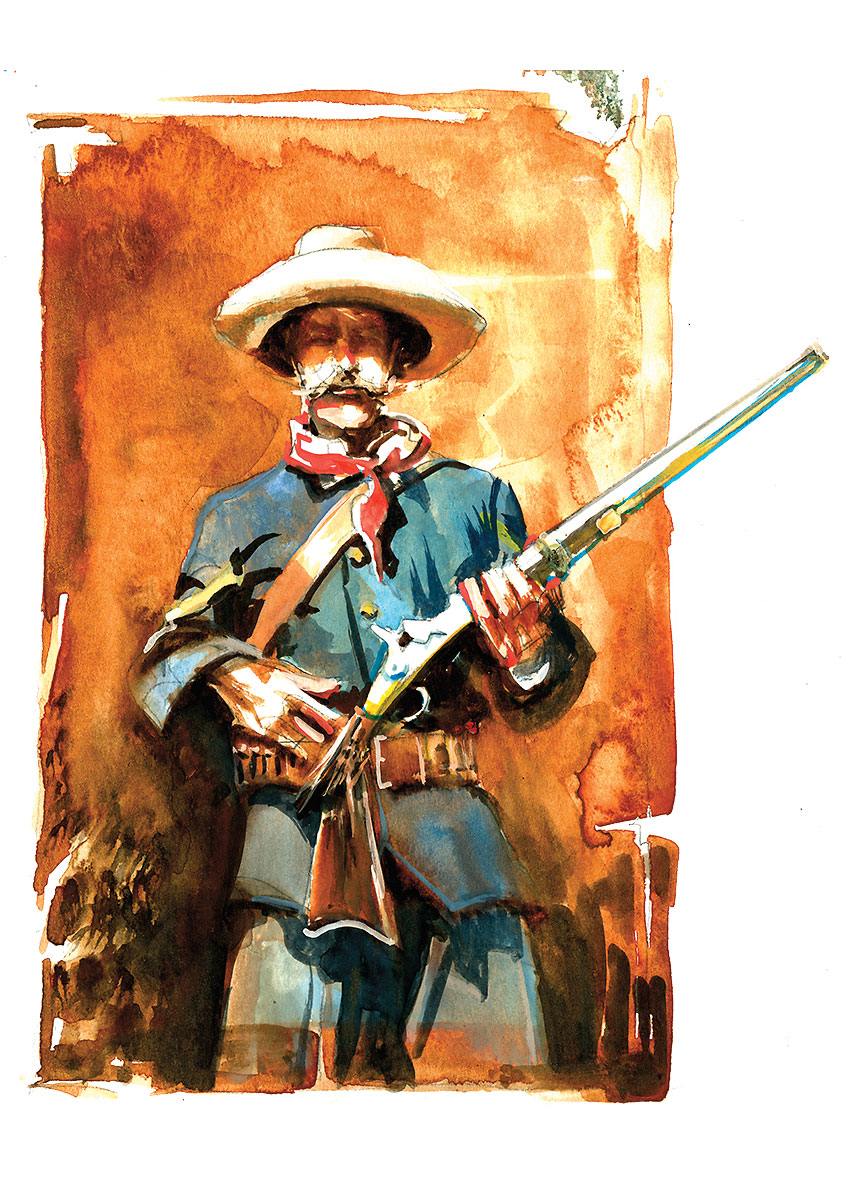

Protecting the Water Carriers

The wounded were crying out for water. “Finally Captain Benteen called for volunteers. I think there were 17 of us altogether who stepped forward. He detailed four of us from “H” who were extra good marksmen to take up an exposed position on the brow of the hill, facing the river. We were to stand up and not only draw the fire of the Indians below, but we were to pump as much lead as we could into the bushes where the Indians were hiding, while the water party hurried down to the draw, got their buckets and pots and canteens filled, and then made their way back. It just happened that the four of us who were posted on the hill were all German boys: Geiger, Meckling, Voit and myself. None of us four were wounded, although we stood exposed on that ridge for more than twenty minutes, and they threw plenty of lead at us. Several of the water party, however, were badly wounded, although we kept up a steady fire into the bushes where the Indians were hiding. Each of us was given a Congressional Medal of Honor.”

—Charlie Windolph

The Mysterious Sniper on Sharpshooter Ridge

One amazing aspect of the deadly snipers raining bullets on the exposed troopers on Reno Hill is that some of them were 900 to 1,000 yards away. This is far beyond the range of most of the weaponry in use by the Indians that day (see rifle range next page), but as historian Michael Donahue points out: “You couldn’t miss basically as you were looking at a solid blue line of blue coat bodies in a straight line lying side by side. It was like standing next to a skirmish line and shooting down it: you are going to hit someone even if you are not a good shot.”

Although most historians concentrate their research on analzying the role of the Indian marksmen on Sharpshooter Ridge, there were also Indian snipers shooting at the surrounded troops from the east.

In recent years, Little Bighorn Battlefield researchers have been able to locate where the snipers were shooting from and what kind of weapons they were using. It was a commonly held belief by most of the troopers that the Indians were not good shots and all sorts of explanations were floated to explain the deadly accuracy of someone shooting from Sharpshooter Ridge. More than likely, it was several Indians who did all the damage. However, after the battle a dead white man was found in a burial tree near the village, dressed in full Indian regalia, and some have speculated a renegade Anglo was the deadly shooter.

Rifle Range

Just to put all of this in perspective, a Winchester has about a 200-yard range (for accuracy), while a Springfield has about a 600-yard range, and Windolph’s narrative mentions a bluff where the Indians are firing from approximately 900 yards away. That is nine football fields away!

After the fires of several years ago, researchers were able to locate where the snipers were shooting from and what kind of weapons they were using. One researcher found the main Indian position to the east of Reno Hill about 800 yards from the troopers. He found about 200 45/55 casings and about 76 .44 Henry/Winchester casings (The archeological survey of 1989 discovered that the warriors had taken the carbines from the Custer dead, and turned them against Reno’s battalion.) According to Michael Donahue, “that last number is crazy as the distance is about 800 yards. They must have been pointing them high into the sky hoping they would drop onto the soldiers.” In fact, many of them did.

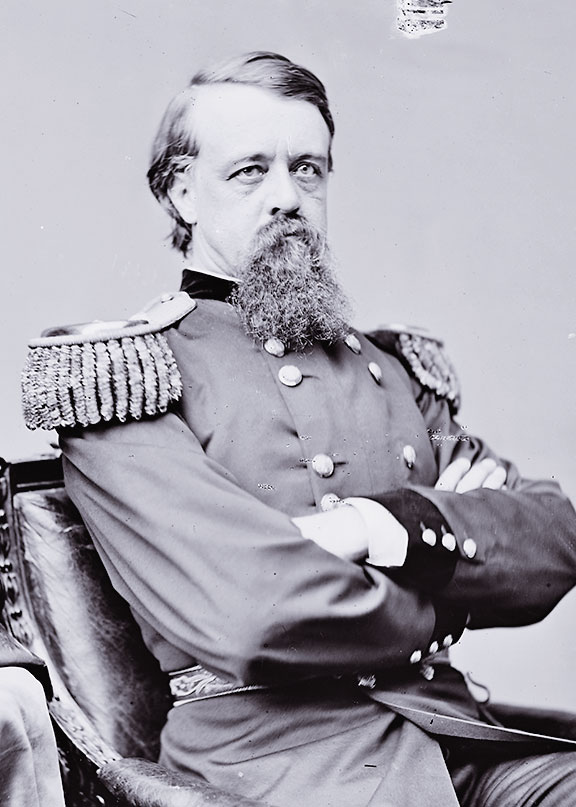

How Were the Indians Dressed During the Fight?

Our perceptions today of how Indians dressed and what their camps looked like are largely based on Hollywood imagery.We just can’t seem to shake it. If one reads George Custer’s official reports of his fights with the hostiles on the Yellowstone in August of 1873, with temperatures around 100 degrees, he

complained very bitterly to the War Department that the enemy were largely dressed in “citizen’s attire” courtesy of the Indian Department and it led to confusion on the part of the troops, they occasionally couldn’t tell friend from foe.

Here is part of Custer’s report: “A large number of Indians who fought us were fresh from the agencies. Many of the warriors engaged in the fight on both days were dressed in complete suits of clothes issued at the agencies to Indians. The arms with which they fought us (several of which were captured in the fight) were of the latest improved patterns of breech-loading repeating rifles, and their supply of metallic rifle-cartridges seemed unlimited, as they were anything but sparing in their use. So amply have they been supplied with breech-loading rifles and ammunition that neither bows nor arrows were employed against us.”

—George Kush

“We buried our dead in the shallow trenches we had dug for the living.”

“I suppose it was early in the afternoon when the firing seemed to quiet down. Now and again bullets would come tearing in, but gradually they became fewer and fewer. Then below across the Little Horn [sic] heavy smoke began drifting southward. Pretty soon it became clear that the Indians were firing the grass. That seemed odd, unless they were getting ready to leave.

“The gunfire had almost ceased and some of us left our trenches and stood in little groups on the brow of the hill. Then something happened that I’ll never forget, if I live to be a hundred [he almost did!]. The heavy smoke seemed to lift for a few moments, and there in the valley below we caught glimpses of thousands of Indians on foot and horseback, with their pony herds and travois, dogs and pack animals, and all the trappings of a great camp, slowly moving southward. It was like some Biblical exodus; the Israelites moving into Egypt; a mighty tribe on the march.

“We thought at first that it must be some trick: that the Indians were only removing their families from danger and that the warriors would soon return and try to overwhelm us. Patiently we waited in our little trenches. The long June afternoon dragged on. The firing had all but ceased. The smoke in the valley had blown away, and the last Indian had gone.

Monument Archive.

“While guards kept their posts, the rest of the men led such horses as were not killed down the steep draw to the river. It was the first drink they had had since early afternoon the day before. Gently we buried our dead in the shallow trenches we had dug for the living.

“Then Reno ordered the whole camp to move as close to the river as possible. We would get as far away as we could from the terrible stench.

“There was plenty of water now for the wounded. And towards evening the company cooks made us the best meal they could. At least we had hot coffee and plenty of bacon and soaked hardtack. It was our first meal in 36 hours.

“Then night came down. We were weary, but while those on guard were awake and alert, the rest of the command slept. But it was an uneasy sleep.

“We still had no word from Custer. We began to suspicion that some terrible fate might have overtaken him. What it was we could only guess.”

—Charlie Windolph

Aftermath: Odds & Ends

After the battle, Reno ordered Benteen to take a few officers and 14 troopers to go and find Custer. Charlie Windolph was one of them. “We trotted quietly up and down the folding hills to the northward. Suddenly, we caught glimpses of white objects lying along a ridge that led northward. We pulled up our horses. This was the battlefield. Here Custer’s luck had finally run out.”

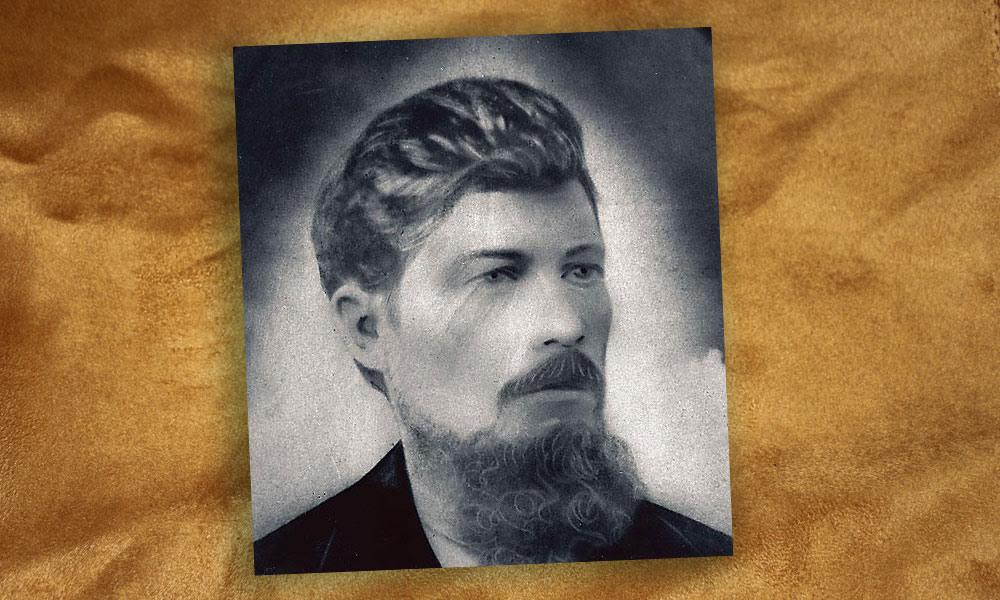

Windolph claimed Benteen made him a sergeant on the field of battle and later, in 1880, Charlie was made First Sergeant, where he served until 1883 when he married and left the Army. He ran cattle, but he admits, “I lost money at it.” From there he worked three years for the Army Quartermaster Corps. Windolph then took a job as a harness maker with the Homestake mines in Lead, South Dakota, where he worked for 48 years, before retiring with a pension.

In old age Windolph loved to sit on his porch and watch the world go by. One of his visitors in the fall of 1947 was a young man by the name of Robert M. Utley who interviewed Charlie before he passed in 1950. That incredible story is next.

Recommended: I Fought With Custer: The Story of Sergeant Windolph, Last Survivor of the Battle of the Little Big Horn As told to Frazier and Robert Hunt, Foreword by Newil Mangum, (Scribner’s 1947; Bison Books, 1987).